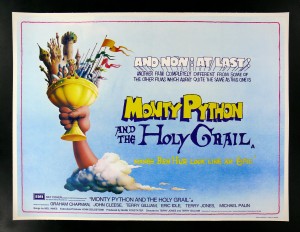

100 Film Favorites – #25: Monty Python and the Holy Grail

(Terry Gilliam & Terry Jones,1975)

“On second thought, let’s not go to Camelot. It is a silly place.”

Today, we sally forth into the final quarter of our Countdown. Thanks once again to everybody who has been following along for the last 75 posts. I hope you’re planning to stick around for just a few more, because the next three weeks or so will take us through the favorite of the Favorites. Basically, what I’m saying is…

GET PUMPED.

We’re starting off Quarter 4 with what is perhaps the quintessential geek movie. Monty Python and the Holy Grail begins with opening credits based on those of the Ingmar Bergman film The Seventh Seal. The background is black, the music is foreboding, and the text is replete with faux-Swedish. I don’t know what it is about absurdist comedies referencing The Seventh Seal, but I think by now we can officially call it a thing. The Animaniacs did it too.

At any rate, the “serious” credits gradually become overrun with increasingly frequent appearances of the word “moose.” The film grinds to a halt, and we are told via intertitle that the crew associated with the opening credits have been fired. The credits resume in a wildly different style, accompanied by flashing colors, mariachi music, and dozens of “llamas” among the listed filmmakers.

This nonsensical opening sequence sets the stage perfectly for what is to come. Strictly speaking, the “plot” of the film follows King Arthur (Graham Chapman) as he recruits the Knights of the Round Table and leads them in search of the legendary Holy Grail. It all sounds pretty straightforward…but things get silly. The film consists of one surreal, bizarre, or scatological gag after another, hammered crudely into the rough outline of an Arthurian quest.

The gags themselves have become classic. The opening shot of the film proper features King Arthur nobly “riding” over a ridge…without a horse. He simply gallops along on foot while his squire takes two empty halves of a coconut and “bangs ’em together.” Later scenes feature an indestructible Black Knight who shrugs off dismemberment as “only a flesh wound,” an attack by a murderous bunny rabbit, and the dreaded “Knights Who Say ‘Ni.'” I could spend a post three times this length describing each gag in detail, but that would ruin the movie. Much of the film’s impact and humor rely on experiencing the divine absurdity of each vignette for yourself. Indeed, it is the unexpected nature of these apparently “random” encounters which gives the film its comic potency. It kind of makes you wonder, therefore, why fans constantly rehash the film by quoting it ALL THE TIME.

Critics of Monty Python sometimes dismiss the team as relying too heavily on “random” humor, grasping for laughs by simply saying and doing one random thing after another. But while some of their weirdest material (an animated hedgehog repeatedly shouting “Dinsdale“, for instance) does approach Dadaist levels of randomness without producing comic gold, most of the Pythons’ work fits squarely within the standard “rules” for comedy. Let me explain what I mean: The best definition of comedy I have ever read describes it as resulting from “overlapping but incompatible frames of reference.” Essentially, comedy “works” because the set-up of a humorous situation leads you to expect one thing, only to have a twist or punchline which presents something odd, idiosyncratic, and “incompatible” with that established expectation. You expect one thing, only to have something unexpected occur.

To be fair, this same juxtaposition can create a situation which is frightening, or simply surprising. So perhaps it is better to say, as a humor professor (yes, apparently there is such a thing) at William and Mary told me, that humor is a particular kind of inconsistency which amuses us; pleases us; challenges our perceptions “in a good way.”

Thus, humor must first lead us to form that initial frame of reference – to make us expect something. Truly “random” humor is unfunny because it fails to create expectation in the viewer. But the most acclaimed Monty Python sketches are those which are absurdist rather than random. These sketches present an absurd situation, and feature characters who either balk at the absurdity around them or simply operate within the absurdity as though everything is perfectly normal. Both situations create humorous incongruity.

In the first case, the character who balks at the absurdity serves as the “straight man” to the wacky antics of people around him, simply hoping to proceed with his day in a modicum of decorum and civility – in other words, the Bert of a Bert/Ernie dichotomy.

In the second, more “absurdist” scenario, the characters act as though things are perfectly normal and logical, despite the bizarre nature of their situation. This is humorous both because such gags often begin with a fairly standard setup and then introduce an element of absurdity, leading us to expect one thing but be presented with another, and because in such a situation we ourselves become the straight man, trying subconsciously to impose on the “silly” chaos the logical order we believe ought to be there.

Much of the humor in Holy Grail results from Graham Chapman as Arthur playing the “straight man” to his entire world. Every wacky thing that happens is much to the inconvenience of the primarily stoic and noble King. He chops apart an adversary, who nevertheless refuses to acknowledge defeat. He fails to rule over (“oppress”) anachronistically progressive peasants. He has large quantities of excrement poured on his head.

And yet at other times Arthur goes along with the absurdity as though it were perfectly logical. Like the other knights, he sees no distinction between “traveling” via coconut and actually riding horseback.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail was sketch comedy team Monty Python’s first feature film with a continuous narrative, released in theaters a year after the conclusion of their television series, Monty Python’s Flying Circus. In some regards the film still feels broken up into “sketch” chunks based around particular gags, but at least the story does have a beginning, middle, and end. Well, a beginning and a middle at least. The climactic battle, and the film itself, is cut short when the modern-day British police arrive on the field, arrest Arthur and Lancelot, and seize the camera. But hey, two out of three isn’t bad for a first effort.

Since people might ask…maybe…I would like to comment briefly on the other two Monty Python feature films which followed Holy Grail.

–Life of Brian: A protagonist with my name gets mistaken for Jesus and is subsequently worshiped by adoring throngs. I’d be down with that, but the Brian of the story is played by Graham Chapman, once again serving as the world’s straight man (perhaps ironic, as Chapman was actually gay). He repeatedly encourages his “followers” to think for themselves and not to worship him, but ends up being made a martyr anyway, dying in a mass crucifixion at movie’s end (but not before Eric Idle sings him the infectious, and instructional, “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life” from an adjacent cross). The film is a humorous critique of many of the absurd aspects of religion, but also, more broadly, of the effects of misunderstanding. Though it didn’t make my Countdown, I’d still give it a “must-watch,” and many critics rank it above Holy Grail, with some dubbing Brian the best British comedy film ever made.

–The Meaning of Life: This film is much more disjointed than its predecessors, returning somewhat to the fragmented sketch format of Flying Circus. The various bits are only “connected” in that they each revolve around a pivotal event in life, from conception (remember, “Every Sperm is Sacred”) to death (avoid eating contaminated “salmon mousse” whenever possible). This is probably the “weirdest” of the Python films, and it drags somewhat in the middle. But it’s a great movie to pop in late at night while sitting, half-dozing, in a comfy chair. There’s nothing quite like lapsing in and out of consciousness amidst bouts of highly-concentrated Python absurdity. Oh, and as for the actual “meaning of life” itself, “it’s nothing very special: Try to be nice to people, avoid eating fat, read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, and try and live together in peace and harmony with people of all creeds and nations.”

I’ll close with a final question. I’m open to your feedback: Does watching Monty Python and the Holy Grail as a child transform one into a nerd, or does being a nerdy child compel one to watch Monty Python and the Holy Grail?

Chicken and the egg, my friends.

Chicken and the egg.

—

Brian Terrill is the host of television show Count Gauntly’s Horrors from the Public Domain. You can keep up with Brian’s 100 Film Favorites countdown here.