Rating: 4 stars (out of 4)

Bull Durham is far and away the best sports movie of all-time, but I hate to classify it as much because it’s also so much more. It’s a great romantic comedy, a very funny movie, a very poignant movie, and when all put together, an exceptional piece of art. Refusing to conform to anyone else’s conventions, consistently surprising with its charm and inventiveness, and brilliantly written and acted, it only gets better with repeated viewings.

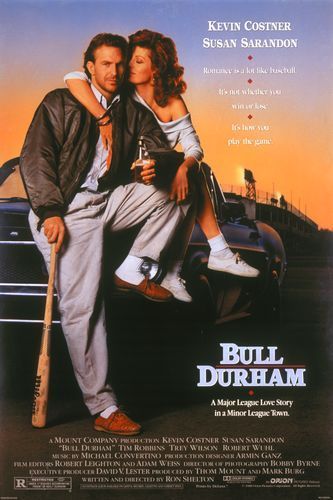

Written and directed by a man who spent many years in the minor leagues himself (Ron Shelton), Durham centers on the single-A baseball team of the Durham Bulls. Their star pitcher is Ebby Calvin “Nuke” Laloosh (Tim Robbins), whose velocity can match the best of them but who often has little control over where his pitches are going. A talented but aging minor league veteran, Crash Davis (Kevin Costner), is brought on to be Nuke’s personal catcher and prepare him for the majors. With one man destined for potential stardom and another hoping that single-A ball suffices as a replacement for such, one possessing great physical gifts and one intellect, the two have a complicated friendship, and Annie Savoy (Susan Sarandon) spices it up even more.

Annie is a baseball nut who chooses one player a year to sleep with, which said player generally follows with the best season of his life. Sarandon has many scenes with both Robbins and Costner, and the sexual attraction between both pairings, especially with Costner, sizzles. Annie’s sexualized, to be sure, but she has her principles—“I am, within the framework of the baseball season,” she tells Crash, “monogamous.” She also has other loves, in particular poetry, which she reads to guys foolish enough to think they might sleep with her on the first night.

As incendiary as the romance is here, the baseball scenes are better. Nuke sets new league records for strikeouts, walks, hit basemen, and hit mascots in a game. There’s not a single pitcher in a baseball movie with great velocity and poor command—Wild Thing, anyone?—not modeled after Nuke. But Shelton doesn’t make him out to be a clown—he’s just a young buck who, as Annie notes, is not cursed with self-awareness. When he ignores Crash’s advice or slacks off in his game preparation, it’s only because he doesn’t know better, not because he’s trying to make noise. Robbins’s ability to make him so childlike and yet believable is particularly impressive.

Though Crash and Nuke meet via a bar fight, they settle down, and their interactions drive the film. Crash ends a fight by telling Nuke to hit him in the chest with a baseball from 15 feet, which he can’t do once he starts to think about it. “Don’t think,” Crash tells him. “It can only hurt the ballclub.” On the field, Nuke has an unfortunate habit of shaking off Crash’s pitches, which invariably results in a home run. Robbins’ “You told him I was gonna throw the deuce, didn’t you?” after the second tipped pitch is priceless.

With just these components, Bull Durham would be a winner, but the film’s gravity and intelligence sneaks up on you; only by the end may you realize what a serious film it really is. Note, first off, how Shelton eschews all sports clichés. The Bulls never bond together to win anything. No struggling player saves the day at the end, and the manager proffers no long-winded inspirational speeches. The film, rather, opens our eyes to the often contradictory world of minor league ball, with players who may spend their entire careers there, hoping for a shot at the big leagues, enduring the lengthy bus rides and few fans and small compensation because they love to play. When Crash recalls his three-week stint in the majors earlier in his career, the other players listen in awe, as though he’s speaking of a priceless jewel that they will never find.

I could write pages and pages listing every great scene in this movie and commenting on the pitch-perfect tone that the actors strike. There are Crash’s mound conversations with Nuke (“Strikeouts are boring; besides, they’re fascist. Throw some more ground balls, it’s more democratic.”), his accusations (“You don’t respect yourself, which is your problem. But you don’t respect the game, and that’s mine.”) subtle teachings (a rant about shower shoes effortlessly illustrates the differences between the two), his rising sexual tension with Annie (“You know, having a conversation with you is like a Martian talking to a fungo”), and on and on. In almost every scene, I can identify a place where it could have gone off track, where a lesser writer would have taken it, and I’m constantly impressed, no matter how many times I’ve seen it, with Shelton’s touch.

The film’s final act is contemplative and almost somber, as Crash works out his problems for good with both Annie and Nuke. Though Nuke and Annie are more vibrant and Robbins and Sarandon are lightning in a bottle, Crash is the film’s heart and soul, the character with whom Shelton clearly identifies. In particular, his philosophy comes out in an exquisite scene at a bar when Nuke wants him to celebrate his promotion to the minors. When Crash talks about the vagaries of the game and then asks Nuke, “You still don’t know what I’m talking about?” he knows that, at the very least, he does, and that’s enough to keep him coming back.

Very persuasive arguments. It’s not my favorite sports movie simply because it doesn’t move me emotionally the way Rudy does — but that movie’s less about the sport than Bull Durham is. Still, this movie gets four stars from me too.