In our last installment, we looked at a filmmaker who began his official filmography when he was nine years old. Today I’ll be talking about a game I’ve been working on since I was nine. Or rather, a story I started when I was nine which became a game when I was eleven. Maybe it’s no Cinemassacre.com yet, but remember, James Rolfe had a ten year head-start.Whether or not it ever “takes off,” Razor in all its forms has given me and my friends countless hours of fun, fantasy, and, often, confusion.

1. THE ORIGINS

The Razor saga (inasmuch as it actually exists) follows an adolescent wizard as he trains to become a master of magic. Along the way he find friends and fights foes, and in the end must battle a dark power threatening the land and confront the secret of his parentage. I’ll be the first to admit that it’s boilerplate fantasy stuff, with elements shamelessly pilfered from perhaps twenty different places. Early on, Razor’s look was more or less a copy of Link from the Legend of Zelda – the story began forming in 1999, a year after I’d been captivated by the release of Ocarina of Time. But I drew from other sources as well. The wizard-training narrative was heavily influenced by the Merlin television miniseries, also released in 1998. And I can’t dismiss the impact of Pokemon, Aladdin, Jurassic Park and – sad to say – even a teensy bit of Star Wars: Episode I. Basically, throw all 90s fantasy media into a blender (or a 9-year old brain, which is essentially the same thing) and the resulting slurry is Razor.

From blatant Link ripoff to spiffy (if generic) fantasy protagonist in 3 easy steps! (Razor in 2001, 2010, and 2014 – the last by a better artist than myself)

Over the years the story developed and expanded. Romance found its way into Razor’s life, as did frog-men, laser camels, a giant robot and even (who’da thunk?) some time travel. World maps and family trees grew, and soon Razor expanded into other areas of my life. The main party members lent their names to my N64 files and Oregon Trail travelers, and I “sailed” a Razor-themed boat model in my scout pack’s rain-gutter regatta. The first written version of the story was a short play I cobbled together in 5th grade, and I made more concentrated efforts to commit it to paper throughout middle school (one version of which is probably still floating around somewhere in the archives of fanfiction.net). None of these attempts yielded much more than 10 pages or so, but I did eventually nail down a rough outline of the “arc” – it’s a trilogy, obviously – and fully intend to actually power through it some day. NaNoWriMo just might be the needed kick in the pants.

But this post isn’t about Razor’s character, or even his story, per se. It’s about a single branch of the “franchise” which has grown and thrived more than any of its counterparts to date. Let’s go back to the summer of 1999. It was the era of trading-card games: Brands like Magic: The Gathering and particularly the Pokemon “TCG” were taking the world by storm. At scout camp, my friends were making games of their own, with precise card design and detailed rules of play. The two most popular were called “20 Card Bomb” and “Citizen.” I never played much of either, but if memory serves the former emphasized action, with players trying to cause and/or avoid explosions, while the latter was a strategy game based on feudal-era government. Both showed skilled and thoughtful game design, and the braggart in me feels compelled to point out that both game’s inventors, like the four main Earn This writers, wound up attending TJ. 20 Card Bomb fever swept the camp, and several more boys tried their hands at creating card games. Without much thought, I sketched out a few basic cards on a piece of construction paper. But these were more in the vein of “classic” trading cards, in that they featured information about the character on the card. There was no way to play an actual game with them. Then I put the handful of ur-Razor cards aside, and didn’t think of them again until I rediscovered them in a drawer years later. But I never forgot how impressed I’d been with the legitimate quality of 20 Card Bomb and Citizen. And so, in the summer of 2001, during some downtime at my grandfather’s house in a small coastal town in Washington state, I headed out to the RV with a stack of index cards and a few sharpened pencils, and made another go.

2. THE GAME

It would be a Razor game, with a combat system vaguely similar to Magic or the Pokemon TCG. These battles, which would often pit protagonist characters against their allies, would need to be separated in some way from the series’ “canon.” So I took a page from the book of Indy and dubbed the card game “Razor: Further Adventures” – the canonical series was The Adventures of Razor, but now players could take things “further” in just about any direction they chose.

“Okay,” thought 11year old me. “I’m going to need to include some creatures, so that there will be things to fight against other things.” And so I created creature cards, and saw that it was good. “I’ll also have to work in the human characters somehow.” Thus the good guy and bad guy cards came into being. The characters would of course need a way to use gadgets (Razor’s sidekick, Fitz, is a gadget-crazed amateur scientist), so I threw some item cards into the mix. Finally, to incorporate the magical elements of the “Razorverse,” I made the spell cards, which could be wielded by “wizards” alone. I created one or two examples of each card type, and saw that it was good. And that was the end of the first day in Razor: Further Adventures. And then I rested.

Here’s a (relatively) brief blow-by-blow of the rules, which have remained mostly unchanged since that first day back in 2001. Try to keep up!

CARD INFORMATION:

Each Razor card contains two or three boxes next to the card’s name. These boxes indicate what type of card it is, what element it is identified with, and, if applicable, how much HP the card has. Card Types and Elements are each identified by unique icons.

Card Types

1. Good Guys, identified by a helmet: ![]()

2. Bad Guys, identified by a skull: ![]()

Card Elements

1. B-Movie, identified by a B inside a star: ![]()

2. Dad, identified by a necktie: ![]()

8. Nursery Rhyme (shepherd’s crook): ![]()

9. Plague (boarded-up window): ![]()

GAME PLAY:

(I.) Setup:

- The Dealer looks through the Deck and decides whether or not to remove the cards that do nothing or are too nerdy or complicated.

- The Dealer shuffles the Deck thoroughly.

- The Dealer deals all cards to the players. Don’t worry if some people get one more card than others, it probably won’t give them an advantage.

(II.) Beginning the Game:

- Each Player selects a Good Guy, Bad Guy, or Creature card from their Hand.

- The Dealer counts to three, at which point all players place their selected cards face-up on the table in front of them.

- The Player who has The Ace in his or her hand takes the first turn, and turns progress to that Player’s left.

(III.) Taking a Turn:

- In a turn, a Player may put one human or creature into play, unless that Player already has two humans or creatures in play. If this is the case, one of these cards may be swapped out for another creature or human in the Player’s Hand, or the Player may choose to take one back into their Hand and not play another.

- Each of a Player’s in-play human or creatures has four possible options as to what they can do in a turn.

A. The card can attack, causing the effects described on the card to take place.

B. Any human or creature may use an Item, causing the effects described.

C. Any Magic human or creature may use a Spell, causing the effects described.

D. The player may choose to have his cards take no action.

The player must have at least one creature or human in-play at the end of their turn.

(IV.) The Discard Pile:

- During the game, when humans and creatures run out of HP, or when items and spells are used up, they are placed in a Discard Pile, which acts as a graveyard of sorts.

(V.) Winning the Game:

- When a player has no more humans or creatures to play, they are out of the game.

- The last player to have humans and creatures remaining alive is the winner of the game, and deserves kudos for being one of the few people to have won a full game of Razor.

- All players should congratulate themselves on having finished an entire game.

****

You got all that? In theory it’s simple: Kill your opponents’ humans and creatures, and don’t let them kill yours. But the devil’s in the details, and Razor: Further Adventures gets devilishly tricky real fast.

3. THE ARGUMENTS

In the rules document I copied most of the previous section from, I gave the game’s title as “Razor: Further Adventures – A game of fantasy and arguing.” Arguments between players are a core aspect of the game, and advice on how to properly conduct said arguments fills an appendix to the rules:

“Arguing – you’re going to have to do it. Try to determine a group consensus and roll with it. The cards may be modified AFTER the game.”

In the early days (2001-2003), back when nearly all the cards were made by me personally, most arguments arose from discrepancies in wording from card to card. The most common source of confusion was the “any/all” controversy. Some card attacks were describe as affecting “all humans and creatures”…did this mean all humans and creatures on the playing field, or just that the attack could affect any one human or creature, and thus all were fair game to choose from? And what about the attacking player’s OWN cards? Shouldn’t “all” include them, too? I argued in favor of the moves affecting only a single opposing card, but power-hungry players would tend to argue for the maximum damage potential, even if it came back to bite them. Gradually, I began writing “all opponent’s in-play cards” for those few attacks which really did sweep the battlefield, and emphasizing the “any” in all other cases.

Another card gave players the ability to “ask an opponent whether they have a card.” I ought to have specified “a particular card,” because players argued that they could always answer, “Yes, I have a card,” and leave it at that.

People argued when cards were overpowered. People argued when cards were under-powered. People argued when Power fought X-Power. But, as a computer programmer might say, we came to view the squabbling as “a feature, not a bug.” Every game of Razor is like the climactic courtroom scene in a legal drama. Your moment to drag in 20,000 letters to Santa Claus or scream “YOU CAN’T HANDLE THE TRUTH!” When I took an introductory law class in my senior year of high school, I realized that Razor is a game of judicial interpretation: Do you take a “strict constructionist” approach, and follow the cards’ wording to the letter, or do you take a more liberal, flexible approach? Do you try to deduce the “original intent” of a card’s author?

And it only got worse – or better – when other people started making cards. Some used different lingo: Humans and creatures are all well and good, but what identifies a “monster?” What if a card has two elements? How do you handle a card which appears to be a Creature-type Item, without an element? Some people even created intentionally ambiguous cards. The “Book of Words” card requires its player to choose two words for the dictionary. If group consensus determines those words to be “good,” “something good will happen” to the player. The nature of the “good something” is presumably up to group consensus as well. Or the karmic balance of the Universe.

Here’s a five minute video from 2008 of my friends and I arguing over what happens when the “Live and Let Dig” card is finished “digging.” Several other cards’ effects, including the Book of Words, are also at issue:

4. THE COLLABORATIVE NATURE

The many artists of RFA: (Top) Alex L, Tom, Steven, Chris; (Bottom) Rutger, Brian, Drew, Alex M)

Sometime around 2003, I put the stack of Razor cards (numbering somewhere around 65 at the time) away. It was a gradual process, but after a while I just wasn’t playing anymore. Chalk it up to starting high school, or going on fewer camping trips, or mere boredom. But in 2006, the summer after my sophomore year (coincidentally, right around the time I first saw Troll 2), Razor came back with a bang. I chanced to dig out the deck at a gathering with my friends, and they hit on the idea of making their own cards. Now a Razor card could come from anywhere. Do anything. BE anything.

As might be expected, things got weird.

Soon there were cards like “Crying Honey,” which requires a player to cry on cue, or to make someone else cry within four minutes. There was a card which “Bizarroed” other cards, reversing their effects (particularly strange when applied to the Contagion card…we soon had “contagious healing” running rampant throughout the deck). There were cards which triggered staring contests, or mandated that players consult dice, clocks, or color wheels.

This influx of “new blood” revitalized Razor, and boosted its popularity by an order of magnitude. Every time I played the game with new people, they would want to make their own cards afterward. And I played it with a lot of new people: I started bringing the deck to my high school homeroom, where it developed a small but devoted following. At our all-night “Junior Campout” party, we played Razor in a tent on the baseball field, huddled by the light of a lantern. When I went to Germany the summer before my senior year, I brought Razor across the Atlantic, and hooked my fellow travelers on the game. We played in the tourbus instead of looking at the Alps. And on our last night in Berlin, the German teacher issued an ultimatum: We could make use of our one chance to hit the big city and get a taste of European nightlife…or we could sit in the hotel and play Razor. It was a tough decision.

We played Razor.

5. THE EXPANDING NATURE

Now there were four groups actively contributing to the Razor deck: Me, my old friends from the scouting days, my homeroom friends, and my German tour group friends. As such, the deck nearly tripled in size, finally plateauing at about 160 cards. There were pros and cons to this eternal expansion. On the positive side, you could make just about any kind of card you wanted. Nerdy kids made nerdy cards, like the “Hyperbolic Paraboloid,” which acts as supremely resilient shield for its wielder…at least I think that’s what it does. It requires a lot of math to use.

The freedom to make any card also meant that, if you absolutely hated a certain card, you could make another card specifically to counteract it. Such was the case with “BRUUUUUUUUCCEE!!,” a kind of nuclear weapon card, used primarily as a threat to deter people from getting too dorky.

The major “con” of the growing deck was that each game, the dealer had to deal out ALL the cards. With more cards, the game grew longer and longer. In the most epic Razor game yet completed (Senior Beach Week, June 2008), 10 people waged war for four solid hours. There were two ways to ameliorate this issue. First, some cards were generally excluded from the deck, with what was left out varying depending on the group playing. The cards most likely to hit the chopping block were those too difficult to use (Hyperbolic Paraboloid), those too ridiculously overpowered (BRUUUUUUUUCE!!), those which referenced existing properties (Cthulhu, Peppy Hare), and those which quite simply did nothing (“Movement,” which consisted of a picture of an owl and the text “ALL MY MOTION”). Secondly, people made cards specifically designed to speed the game along, such as “The Next Fish,” which discarded 2 cards from each player’s hand, or “Chairmaster,” which eliminated one entire player via musical chairs.

6. THE TIME WARPS

An opponent speeding up the game isn’t the only chronological concern with which an aspiring Razor champion must contend. One of the earliest cards to explore the potential for absurdity in Razor, and to strike fear and loathing into those who faced it, was the infamous “Time-Warp Device.” Resembling a tricked-out Bop It, the Time-Warp Device is meant to replicate the effect of time-traveling somebody out of existence, by preventing them from having ever been born. “Undo the previous effects of a target card,” it says. “Then discard it.” This is devastating and bewildering for all involved, as everyone scrambles to calculate an “It’s a Wonderful Life” scenario, assuming the affected card never existed. If that target card has been in play for any more than two turns, it’s almost impossible. It was even worse originally, when the player was allowed to use the Time-Warp Device THREE TIMES.

While no other card packs quite the same time-punch as the “TWD,” we made up for it by having not one, but two other cards which allow the player to undo an opponent’s previous turn.

In addition to this time-traveling trio, there is a single card so feared and complex that it will likely never be used. “The Bonus Turn” grew out of an argument we were having over whether “three turns” had elapsed, to determine whether or not a card was still “deactivated.” Although uttered randomly, the words seemed to possess a primal power, and we forwent the rest of the game to have a deep discussion on what exactly a “Bonus Turn” might entail. We came up with a card which emulates the bizarre style of time travel found in Bill & Ted’s Big Adventure: You announce your intention to “time travel” back a certain number of turns in the game chronology, with your current in-play cards serving as your “time travelers.” The “present” changes based on the effects that would have / have transpired based on you having had your current hand at the specified point in “the past.” Chances are you’d probably need a computer (or several) to ever see a true Bonus Turn at work, but hey, what better excuse to make Razor: Further Adventures Online?

7. THE HAND-CHANGING

In amongst all the time-hopping, color-matching, and crying, cards are constantly changing hands. This happens for a variety of reasons. Fitz’s “Invent” ability allows him to snatch an Item card from someone else’s hand, while Ion (the story’s lead villain) can use his “Charisma” to win over opponents’ weakened fighters to his side. “The Trading Card” passes from player to player in exchange for other cards. But the most potent cause of card-swapping by far is “14Spike,” the cheeky robot pictured above. 14Spike’s player selects a word (specifically, a noun), without telling the other players what word he or she has chosen. Then, each time other players speak the word, they must pay a one-card toll to the player with 14Spike. This makes people very angry. As the card was originally written, the player could pick “any word,” regardless of parts of speech, and the go-to choice was either “a,” “the,” or a swear word, sure to be uttered as the cards started flying. This prompted the requirement that the word must be a noun…but “card” and “turn” are still reliably effective choices.

Not even the discard pile, or “graveyard,” is safe from the hand -changing maelstrom. “Time Absorber” allows a player to discard their entire hand and replace it with an equal number of cards from the discard pile. This can be a complete game changer if done late in the game, suddenly reintroducing powerful cards while other players are on their last legs.

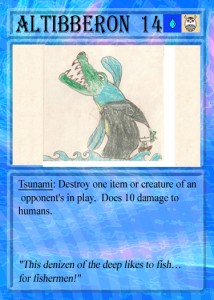

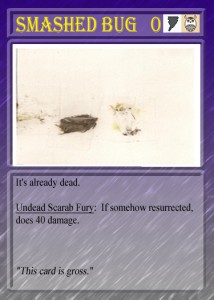

8. THE SMASHED BUG

One time, I smooshed a moth with an index card and decided to include it in the game. The “Smashed Bug” isn’t especially useful, however, as it begins the game already dead. If resurrected somehow, it does possess a powerful attack…but convincing everyone you’ve found a way to do that requires a rare talent for arguing.

The Smashed Bug’s most notable accomplishment came in 2009, when I was tangentially involved with the “JUMP!” literary magazine at William & Mary. I attended a handful of “staff” meetings, but missed most of them due to band obligations. When submissions time came, I sent in several short stories and poems, but all were rejected. I even tried some “artsy” stuff, to match the near-surreal tone of the magazine’s weirder selections, but with no luck. Finally, I scanned the smashed bug and e-mailed it to the editor.

A month later, it ran as a full page of the magazine.

9. THE SCROLL

In the summer of 2010, I remained in Williamsburg after my sophomore year of college. I stayed in a dorm and took morning classes, but this left a lot of free time in the afternoon and evening. I decided I should undertake a large-scale project of some kind. Inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry (and in turn the Bedknobs and Broomsticks opening credits), I chose to depict the subjects of each and every Razor card engaged in “battle” across a single, lengthy scroll. Over the span of six weeks, I poured maybe 100 hours into this thing. While it’s no masterpiece, I’m proud of it, if only for the commitment and perseverance it represents. The scroll measures approximately 1′ x 11,’ and all 164 cards which existed at the time are represented (only a few have been made since). Take a good, “Where’s Waldo”-style look: Some of the altercations and pairings going on are quite funny, if I do say so myself. See if you can spot the two figures amorously sobbing over a shattered vial of love potion, the dark wizards who are putting aside their differences and shaking hands, Torgo from Manos: Hands of Fate, and Troll 2‘s Grandpa Seth. Oh, and the Smashed Bug is there, too (a beetle this time).

Here’s the scroll, scrolling. The music is “My Way” by the chiptune band I Fight Dragons. The resolution isn’t fantastic, but I defy you to do a better job scanning an eleven-foot-long document.

10. THE FUTURE

Razor: Further Adventures is a game of possibility, that changes and grows with time. It’s been a part of my life for 13 years, and Razor himself for a full 15. Few friends have been with me longer. Though it may not mean much coming from its creator, I’ve had a lot of fun with the game, and others who play seem to enjoy it too. Razor’s own story, while not the most original fantasy yarn, preserves a kind of childhood logic which those I’ve shared it which have found endearing. It’s the adventure that lived in all of us as kids: a personal legend spun from bits of the stories we heard and the world we lived in.

It is that spirit, combined with the “anything goes” nature of the card game, which a group of friends came to me last year with the hope of channeling into a Razor video game. Though progress has been slow, we’re happy with the concept: an RPG set half in the “Razorverse” and half in a twisted version of the 1990s. I won’t say any more here (my teammates are more tight-lipped than I), except that I’m grateful something as silly as a game scrawled on index cards more than a decade ago has continued to resonate with people, and to inspire them to pour their own time and efforts into growing Razor and his world.

Awesome. I loved playing Razor and I want to play it again. I very much enjoyed the backstory. But now I also kind of want to program a version Razor: Further Adventures for PC (not an RPG spinoff, but an actual adaptation of the card game — let’s confer on this).

Also, if you’ll recall, Razor has inspired me to make my own card game… I’ve completely scrapped my progress about three times and started from scratch, but a game alternately titled “Long Live the King” or “King Dan” (feedback is mixed on which title is superior) will some day come to fruition.

Who’d have thunk 20 Card Bomb and Citizen would have been the catalyst for something still so great a decade and a half later.