Topping the UK charts is as easy as a² + b² = c².

The Music Information Retrieval (MIR) team at the University of Bristol recently announced to the world that they had devised a mathematical formula that indicates what qualities of a song are important, and to what degrees, in determining whether that song will eventually make it into the top 5 spots of the UK Top 40. Their research is on display in a very pop form at scoreahit.com. And in the interest of fairness, you might want to take a glance at how they present themselves before you hear my opinions.

To me, as a lover of music and an acquaintance of the industry, the idea of an equation for success smacks of mythology. While I recognize that claims of pop music becoming both formulaic and hit-driven are patently true, it’s just as true that not every cookie-cutter record becomes a worldwide bestseller. I choose to believe that what separates hits from misses, if it is predictable at all, has little to do with song structure. (It’s probably nothing noble either; I’m thinking along the lines of publicity funding.)

Press coverage, at least what the team links to, has uniformly been reminiscent of Bristol’s official release. Maybe that’s a comment on journalism. But, if you’ll follow me through the jump, I’d like to show you the problems I find with this particular study, its results, and its presentation. In the process, I hope to completely maim your dreams about any holy grail of a Hit Equation.

Philosophy

“What are the features of a perfect hit song? Is there any equation describing a hit? Are there any features which are changing importance through the ages?”

Armed with 23 “features” by which to describe a song, the MIR team sought to answer these questions. Their approach was to see which of these features—danceability, loudness, harmonic simplicity, etc.—were prominent in UK Top 40 songs since 1960, then to find trends. Specifically, trends that distinguish between the top 5 spots and the bottom 10 spots. No distinctions were made based on genre or song style except as captured by these features: that is, the presence of a ballad at #1 was taken as a sign that a top 5 song ought to be slow. If #2–5 were dance and rock tracks, then the team’s math would suggest that a top-5 song should actually be fast, but the conflict between #1 and the others would be interpreted as a signal that speed doesn’t matter as much as other features might.

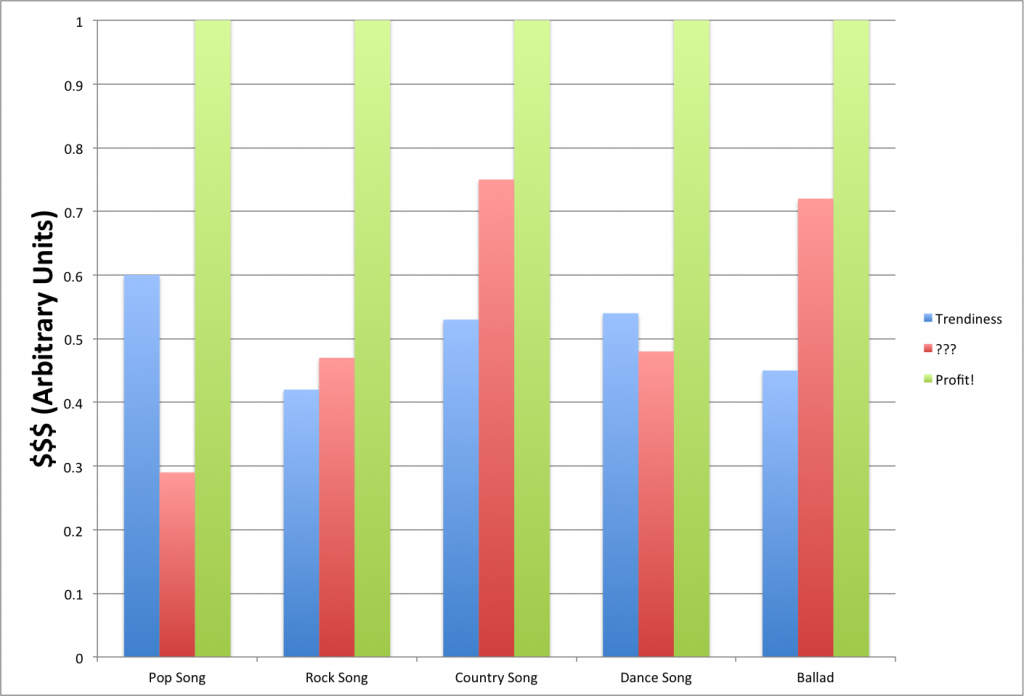

Averaging out qualities across the top 5 like this (although, it’s important to note that they are not literally taking an average! see below for more on their fancy math) is perhaps okay for a first attempt. In a thorough analysis, I’d like to imagine that the public has some desire to keep, let’s say, one ballad in the top 10 or so at all times, so that ballads compete against each other for dominance but not against the rest of the charts. If anything, they would have a separate equation for themselves. You could say the same thing about a country song, or a few club tracks: not all records are competing for the same spot in our hearts!

Features

If you had to name just 23 things that separate a classic from total garbage…

Scratch that. What if you only had to name 11? The Bristol bunch irritates me by misrepresenting their set of features. Let me list for you ten of the qualities they kept in mind:

- Loudness Variation

- Non-Harmonicity

- Tempo > 190bpm

- Tempo 170–189bpm

- Tempo 150–169bpm

- Tempo 130–149bpm

- Tempo 110–129bpm

- Tempo 90–109bpm

- Tempo 70–89bpm

- Tempo < 70bpm

Did you catch what happened there? It was subtle. Scientists are subtle like a fox. (If you don’t know, by the way, bpm is “beats per minute”—how many times you tap your toe.) So, how many features did I just list: three or ten? They play a similar trick with time signature and with the length of a song to get up to “23.”

Subdividing features, while not an entirely rotten practice, is something the MIR team did to cover up a more serious shortcoming of their model. The Hit Equation scores a song linearly in each feature. If algebra class was a long time ago, let me explain what that means: according to the Hit Equation, if being loud is good, then being louder is better. Without limit. Holding all else equal, a song that breaks your eardrums is king. Even if it doesn’t score well elsewhere! A linear model is one that sees some features as more important than others, but one that cannot admit a “sweet spot” in any feature. It’s pure min/maxing.

By breaking up, say, tempo into eight features, the team was able to force a sweet spot. If “Tempo 130–149bpm” scored best, then that’s where a song wanted to be. There are eight other features that were not subdivided, which means no sweet spot.

One other comment here. The website is very good about showing in detail how a song’s “high-level features” such as Non-Harmonicity were defined mathematically. (It’s complicated but it works!) Two of them, however, Energy and Danceability, were extracted from a song information database run by The Echo Nest, who does not publicize their definitions. These features are not derived in a straightforward way, and whether they are trustworthy or not, it’s frustrating to be denied access to their real meaning.

Science

I told you these guys weren’t just taking an average. What are they doing?

The MIR team explains their technical method: machine learning based on an application of Tikhonov regularization known as a Time-Shifting Ridge Regression (TSRR). Whoa, big words! Don’t worry, yours truly happens to be a scientist, and this part actually turns out to be kosher.

TSRRs are good things. Using all of the UK Top 40 since 1960 as the input to “train” their equation is a good thing. It means that a computer gets to look at all those songs, knowing which ones actually made it to the top 5, and figure out what qualities must have been important. The smart, hard-working computer spits out an equation that can then be used to predict how successful a new song might be, based on how it fits into the picture of all these other hits through the years. With no scientific caveats, the Bristol bunch was good up to the point of generating their Hit Equation (v.s. and v.i. all of my non-scientific comments).

Note [Edited Feb 23, 2012 by the author]

Previously, at this point in the article, I alleged a heavy criticism at the MIR team based on my own faulty assumptions about their method. For this I apologize to all those involved in the project. To be clear, I had stated that the Hit Equation trained their TSRR with all of their song data from the past 50 years, then applies the resulting equation to the same set of songs. This is false. Each prediction made by the Hit Equation is on the basis of the preceding data, i.e., what songs charted earlier in time than the one being scored. Only after a prediction is made in this way, and added to the team’s running Results, is the actual success of that song taken into account, modifying the formula as appropriate so that it can be applied to future songs.

The Perfect Song

One cool thing the Hit Equation manages to do is evolve through time. Because of the power of the TSRR method, the Bristol bunch is able to produce an equation that depends on what year and month you’re looking at, which accommodates the changing taste of the public.

(They made a YouTube video that shows the importance of each feature as it changes over the years. I’d like to point out, as you watch, that Energy has always been a detractor. The Hit Equation predicts that the public has been staunchly opposed to energetic music at all times.)

But let’s jump to today. As of the beginning of 2012, what makes a great song? According to the Hit Equation, the ideal top-5 hit is…

- loud, danceable, and over 190bpm, but crucially must be low in energy;

- non-harmonic (lots of “noise” outside of the dominant chord structure) but in a major key;

- lasts between 6 minutes 15 seconds and 8 minutes 44 seconds;

- and has a tertiary time signature, i.e., you tap your toes three or six times for every time you bob your head.

Huh, come to think of it, that describes just about all of my favorite songs of the last year! Thanks, scoreahit.com!

Taking the Hit Equation for a Test Drive

The team has designed a free app that allows you to name almost any recorded song, or even upload one of your own, and see how it scores using their formula. Let’s see what it says about the best-selling songs in the UK of all time:

|

Artist |

Song |

Sales in the UK |

Score out of 12 |

|

Elton John |

Candle in the Wind 1997 |

4.8 Million |

10 |

|

Band Aid |

Do They Know It’s Christmas? |

3.5 Million |

5 |

|

Queen |

Bohemian Rhapsody |

2.1 Million |

5 |

|

Wings |

Mull of Kintyre |

2.0 Million |

2 |

|

Boney M |

Rivers of Babylon |

1.9 Million |

5 |

Some might say that the bestselling singles of all time are likely to be exceptions to the rule. I’d counter that an exceptional song that follows the rules is likely to sell more copies than an exceptional song that breaks them all, since this is a popularity contest. The MIR team mentions, on this point, that the Hit Equation by design predicts that novelty is a bad thing and that songs breaking the mold will flop, which is certainly true the vast majority of the time.

But that’s not all: they have at least two more excuses for why some of the bestselling singles of all time would score so low. First, they can’t be held responsible for charity releases, such as the first two in my table there. Their sales are surely somewhat less contingent on their musical qualities. Second, the app grades all songs, regardless of release date, on the basis of the end-of-2011 version of the Hit Equation. This is despite the fact that they prided themselves on an equation that evolves through time, and despite the fact that they grade the songs you input by accessing information about them from a database which also contains the songs’ release dates. Oh.

Meanwhile, if you’re wondering what score out of 12 is needed to qualify as a “probable hit,” I’m right there with you, buddy. All I have to go on is this article which uses the Hit Equation to prove that Bruno Mars should’ve won all those Grammys; the author refers to a score of 7-out-of-12 as “squarely in the ‘Hit’ camp.” Ignoring for a moment the logical leap that Grammys are awarded based on the particular musical features used by this formula, let’s just try applying it somewhere that it ought to be quite successful. Here are the scores for the three bestselling singles in the UK of the 2000’s:

|

Artist |

Song |

Weeks at #1 in the UK |

Score out of 12 |

|

Will Young |

Evergreen |

8 |

5 |

|

Gareth Gates |

Unchained Melody |

6 |

8 |

|

Tony Christie f/ Peter Kay |

Is This the Way to Amarillo? |

7 |

3 |

For the sake of comparison, here’s a MIDI that I wrote in high school. It scored a 7.

Other Bits

I’ve probably gone on long enough already, but inquire within if you’d like to hear more of the fascinating things the Bristol bunch did wrong:

- Presentation. The songs they label as Expected Hits, Unexpected Hits, and Hidden Gems are all hand-picked samples that construe themselves as typical representatives of those classes of songs.

- “Interesting” results. Conclusions they choose to highlight include that the rise in popularity of danceable songs coincided with the end of the Disco era and that “music of all qualities is getting louder.” (Surprise!)

- Choice of features. Unable to translate these qualities into math, the MIR team chose to assume that the popularity of a song has utterly no dependence on the quality of a singer’s voice, the instrumentation, the song structure (e.g., presence of a chorus), or the lyrics. Among other things.

- Confirmation bias. A study predicated on the feeling that “all today’s songs sound the same” provides data indicating, actually, a remarkable amount of novelty and variance, and fails to state this among its conclusions.

- Binning. This is a statistics issue, but the way they subdivided features like tempo and the way they chose to compare #1–5 on the charts against #30–40 were poorly motivated and likely became sources of error.

- Honesty. Many of my complaints might be responded to when a formal scientific paper is produced, but it is frankly improper conduct that the team has made an entire website and strongly publicized their project before writing such a paper and making it available. [Edited Feb 23, 2012 to add: My point in this bullet may be overly harsh; my feeling on the matter is colored by a particular recent uproar in my own field of study.]

Forever to Seek the Grail

In May of 1988, a ridiculous novelty single called “Doctorin’ the Tardis” ran to #1 on the UK charts by copy-pasting liberally from already-popular songs. Months later, the artists (who recorded under many names but are best known as the KLF) published the book pictured above, from which I made the word-cloud at the top of this post. It’s long out of print, but you can easily google for the full text.

The Manual explained “How to have a number one the easy way,” and went into elaborate detail about how to steal material, get your sound engineer to actually write your song for you, and focus on publicizing the heck out of your song long before you’ve even recorded it. It’s a very tongue-in-cheek book and a very British book, but I have more faith in the effectiveness of its methods than I do in the Hit Equation.

If you want to find the formula for success in the music industry, ask a successful producer. They know. And they do not have any formulas plastered on their wall. If you want to conduct a pop psychology study, don’t brag about your math and make a website with a “/science” subpage. The public is very gullible, and will believe anything you say because science has a good reputation.

And if you want to put my MIDI on a CD and sell it in stores, knock yourself out. It’s apparently a hit waiting to happen.