What is the most pervasive, systematic flaw in mainstream movies and television?

What’s the common thread? Everyone bemoans Hollywood’s over-reliance on existing source material. We criticize the general soullessness of many movies, the predictably sophomoric humor of many sitcoms, the disaster porn in action movies. I think the biggest problem is none of those, and it begs a question I can’t stop asking anymore:

Why the hell can’t anyone write women?

Despite drawing some occasional lip service, this problem doesn’t truly get the attention it deserves. Oh, sure, you’ll see the occasional think-piece about “Hollywood’s exclusion of women,” or you might hear one of your artsier friends mention the Bechdel test. But we don’t seem to be any closer to ridding Hollywood of its sexism, slut-shaming, and thin female characters who are defined primarily by the men who orbit around them.

The problems start at the top: men control entertainment. According to the Women’s Media Center, 91% (!) of the 250 top grossing movies of 2012 were directed by men. In TV, women comprised 18% of the behind-the-scenes roles of 2012’s shows. The Hollywood Reporter has noted that about two-thirds of characters in entertainment are male (which dovetails with anecdotal evidence that seemingly every movie is headlined by two men and one woman).

Pick any stat you want, the result doesn’t change—men are in charge. And they either a) don’t know a damn thing about women or b) don’t care to construct interesting ones. But why should they bother to, when the easy route of demeaning shortcuts and rampant sexuality has become so accepted?

I could spend paragraphs upon paragraphs simply providing examples, but I doubt any seasoned moviegoer is confused about what I mean. We’ve all seen the personality-free females eager to hop into bed with our protagonists, no matter how few attributes they may have, all at the behest of our fantasizing male writers (Forgetting Sarah Marshall, 22 Jump Street, The Office, Seinfeld, etc.). We’ve laughed at the comedies (American Pie, Knocked Up, This is the End) that paint the few women who actually get speaking parts as either nagging shrews who don’t get to have any of the fun or robotic sex objects. (Like, The Hangover is a good movie, but Stu’s wife is a terrifying creature with few, if any, person-like attributes, who obviously sprang from a male nightmare of marriage. Professionals should be able to do better than that.) We’ve sat through the action movies where the women exist mainly to provide domestic services before being shuttled out of the way so the men can take care of the plot points. (Hell, Jason Bourne became unusual for his lack of chauvinism.)

In certain instances, the entertainment industry’s poor treatment of women smacks us in the face. For example, Aaron Sorkin, although responsible for maybe the best movie of the past half-decade and dialogue so beautiful it sounds like opera, can’t write a good woman to save his life. Because he’s so polarizing—and The Newsroom so unconscionably bad—Sorkin draws headlines, but more often the treatment slips in under the radar, the sexism hammered home silently.

To wit: Even respected classics like Rear Window or high-brow artsy movies like Punch-Drunk Love provide us with beautiful (and weakly developed) women inexplicably drawn to unappealing men, with no explanation given other than ‘the screenwriter wanted this.’ Even quality character pieces like Sideways define the men far more deeply than the women. Even highly entertaining movies like Ocean’s 11 and quality sitcoms like The Office perpetuate the deeply uncomfortable notion that beautiful women must be rescued by a man from the no-good boyfriends they’ve (for reasons passing understanding) chosen, to which they will naturally acquiesce at just the right time. And you could write a graduate-level thesis on the gender-related issues of Hitch, one of the highest-grossing movies of Will Smith’s career.

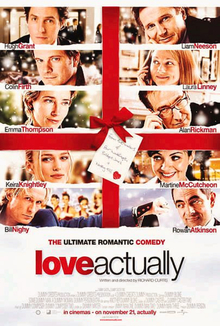

Maybe all of this messes us up; maybe that’s why, when Trainwreck comes along and turns its free-wheeling, sports-hating protagonist into someone who would pretend to be an effing cheerleader in order to woo a man, we consider it some sort of shockingly progressive statement. Maybe that’s why, when we see a movie filled with attractive young women being lusted after by older men who have little interest in any parts of them above their shoulders (and who dictate all the terms of engagement), we lap it up as a ‘romantic comedy classic.’

Unfortunately, the mainstream TV landscape paints an equally depressing picture. Any discussion of the most popular sitcoms of the past generation would have to include Seinfeld, Frasier, Friends, How I Met Your Mother, Two and a Half Men, The Office, and (sadly) The Big Bang Theory. Of the literally thousands of episodes those six shows have produced, how many could pass the Bechdel test? Seriously…10 percent?

On shows like Frasier and The Office. the anachronistic nature of the women clashes violently with a general tone that otherwise purports to be so progressive. It’s really amazing—the gender dynamics on those shows run the gamut from slut-shaming to portraying women as desperate to be completed by Mr. Right (the former’s Roz and the latter’s Kelly are two of the worst female characters ever created) to allowing men to always dictate the terms of relationships. (For that reason, Jim kissing Pam at the end of Season 2 of The Office, coming right on the heels of her saying no to him, always struck me as more problematic than romantic.’) The implication, as always: Women can’t make decisions; we need the men to do that.

This should be a bigger deal than it is. In an entertainment industry long considered a bastion of liberalism, the apathy regarding this inequality resonates megaphone-loud and crystal-clear.

[pullquote]In an entertainment industry long considered a bastion of liberalism, the apathy regarding this inequality resonates megaphone-loud and crystal-clear.[/pullquote]

When the relegation of females to the backgrounds of our stories happens so consistently, it’s hard to avoid the implication that we think they’re not worth more than that. There’s a reason works with largely female casts (whether Gilmore Girls or Bridesmaids) are immediately branded as ‘girly’—and, by extension, second-rate. We’ve conditioned ourselves to care about men’s stories and men’s lives, but not women’s. Maybe that’s why all of the praise for Rear Window somehow overlooks the implausibility of Grace Kelly being attracted to the callous doofus whom we never once see treat her well. Maybe that’s why Sideways draws virtually no comments noting that it’s constructed so that we care about the men’s lives and not the women’s, so that the men are three-dimensional and the women two-, so that the male protagonist’s arc is competed by his wholehearted pursuit of a woman who probably shouldn’t like him. Maybe that’s why the continued poor portrayals slip by.

None of this is to say that movies like Sideways or The Hangover shouldn’t be enjoyed. But this stuff is out there, it reflects–and perpetuates–people’s behavior, and it should be noticed and discussed. And it’s out there in places that are easy to miss; for example, the Netflix summary for the movie Cruel Intentions refers to Sarah Michelle Gellar’s character as “promiscuous” and says nothing of the sort about Ryan Phillippe’s–even though a) the adjective is wholly unnecessary in the context of the sentence it’s in, and, more importantly, b) he’s far more promiscuous than her. He’s the one who says that he’s bored of sleeping with so many people, not her. But we have to go out of our way to call her promiscuous. Uh huh. The more this type of message gets absorbed into people’s minds, the longer it’ll be before anything changes in our movies.

A somewhat related personal note: I was out to dinner recently with a female friend. Whenever the (male) waiter needed to ask a question that affected both of us–whether ‘we’ were ready to order, whether ‘we’ wanted cheese on our salad, etc–he only looked to me. When he returned the paid check to us, he placed it in front of me, apparently thinking that I look just like an Amanda. It was as though my friend was irrelevant to the decision-making. I don’t think he was being intentionally discriminatory…but if he was writing a movie, he probably would have written the kind of flimsy women we’re talking about. The dinner made me think about the episode of Master of None where Aziz’s girlfriend points out the man who introduces himself to all the men at a table and not the women.

Things like that, and the Netflix summary mentioned above, make me understand that a sizable chunk of this is simply due to outdated beliefs about women and good old-fashioned sexism. But the way movies are put together, from the men in charge of production to the men in front of the camera, exacerbates the problem. I suspect many writers work hard on fleshing out their protagonists and then rely on shortcuts and stereotypes for everyone else, and guess what gender most of our protagonists are? (This can go in the other direction, too; in Bad Moms–written, by the way, by two men–the main characters are all women, and so the ‘hot love interest with no personality’ role is given to a man, played by Jay Hernandez. Is that any better? It’s hard to say.)

People could propose other theories (a discussion of our culture’s greater tolerance of flawed men vs, flawed women could fill an encyclopedia, although that’s mostly just rooted in pure sexism), but really, who gives a damn? Let’s not let our writers off the hook by straining to see why they’ve crafted such shitty female characters; it just needs to stop.

This isn’t just an academic, high-level discussion. It affects how much we enjoy going to the theater. At the end of the day, why do movies fail? Almost always, it’s because you don’t connect with the characters. If you don’t relate to, sympathize with, like, passionately hate, and/or root for the people in the story, your chances of enjoying it are virtually nil. If you do, you can forgive the biggest plot holes and most strained dialogue (the long-term success of James Bond illustrates this). The painful stereotypes and paper-thin female roles make it harder to enjoy movies not only on an intellectual level, but also an emotional one.

Naturally, there are exceptions to this problem. (There was nothing flimsy or embarrassing about Saoirse Ronan’s character in Brooklyn, just to name one.) Anecdotal evidence suggests that teen fare treats its ladies better, perhaps because it’s more often written by women. Don’t Freaks & Geeks, Mean Girls, Gilmore Girls, The Spectacular Now, etc all feature stronger, more compelling ladies than adult works? Wouldn’t you rather be Summer Roberts or Cady Heron than Katherine Heigl’s character in Knocked Up or anyone in a James Bond movie? Isn’t that kind of sad?

Of course, we shouldn’t have to dig up indie flicks, teen melodramas, or the rare overachieving filmmaker in order to not be embarrassed by the women presented to us. As long as the most mainstream, popular, well-funded movies emanate from the pens of writers who seem to think the world should operate as it does on Mad Men, the embarrassment will persist.

When I discussed this topic with my best female friend, she teased, “I guess you’ll just have to bite the bullet and write a character based on me.” She was kidding, but I like it. I’d like our most prominent screenwriters to use the coolest, most interesting women they know as the inspirations for their next leading ladies. It sure can’t be any worse than whatever techniques they’re trying now.

This is one of my new favorite articles on Earn This. Great job. There’s a lot to be said here — this is a massive, systemic problem — but I agree with your main points. It feels like mass entertainment’s gender politics are a few decades in the past.

I like your rejection of the “why?” — Let’s just fix it. Bridesmaids becoming a hit shouldn’t be a major news story. The show Girls gets an order of magnitude (or two) too much coverage in large part because its flawed, unpleasant leads have two X chromosomes, which is unheard of.

Your insight that teen shows often have strong female characters makes me feel slightly less guilty about watching so much of them.

I definitely agree. And actually, 6 of your 10 teen examples (I’m counting a half each for clueless and mean girls) are based on books, which means that the strong female characters weren’t even originally written for the screen.

Everything good is based on a book.