Rating: 2 and a half stars (out of 4)

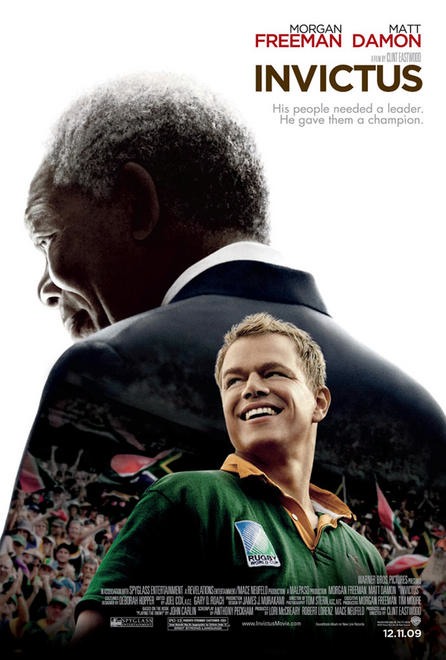

For those who have seen the trailers and are reasonably familiar with the puppets behind the stage, Invictus will probably be much like what you expect. Clint Eastwood’s directorial style—at best, smooth and undistracted, at worst flat—Morgan Freeman and Matt Damon’s dignified acting, and a stirring finish are all delivered as expected. But although Invictus is certainly safe in its own way, it’s not at all the kind of movie one might have expected about Nelson Mandela…nor is it nearly as good as it could have been. This film centering around the famous president of South Africa, elected after spending 27 years in prison, doesn’t delve into his incarceration, The Hurricane-style, or tell a birth-to-present biographical story complete with cries from his estranged family members. Instead, it possesses many hallmarks of a classic sports movie, replete with an underdog we can cheer for and a ceremonial ending.

At the movie’s outset, Mandela (Freeman) has been recently elected president of South Africa, a country in tatters and still filled with racial strife. Blacks are pleased with his election but skeptical of Whites and of the possibility of actual change; meanwhile, Whites wonder whether their dominance will be stripped away. Mandela starts by surprising the Whites on his staff by telling them they won’t be fired, then begins contemplating how to start unifying his country. He cares not about revenge but rather wants whatever will help his country heal fastest. And to that end, he turns to rugby.

Captained by Francois Pienaar (Damon), the national rugby team, the Springboks, have long been ignored or condemned by the country’s Black population. Playing a largely White sport (as opposed to soccer), the Springboks have represented apartheid for years. Blacks want the team and its colors disbanded, but Mandela sees a different angle: he wants the country to rally around its team in the upcoming Rugby World Cup. Mandela, shrewdly, seems to sense the transcendent power that sports victories have for people, and he envisions a winning Springboks team as a potential beacon of inspiration for his countrymen, regardless of their skin color.

Eastwood and writer Anthony Peckham carry much of the film with grace and effective understatement. But given their decision to focus so much on sports—and rugby, no less—and not the historical figure, their inability to generate the proper gravity of the climactic game has to be considered a damaging flaw. That this rugby team, considered a laughingstock before the Cup, actually managed to come together and win after Mandela encouraged them to do so is mind-boggling—the kind of thing that would be laughed out of the cutting room floor of a proposed fictional tale. Invictus, sadly, imparts absolutely no sense of the moment, of the magnitude of the success. Not only is there no explanation of how the team improved or of how improbable that was, the film, and its climax, doesn’t feel nearly as ‘big’ as it should.

What’s more, we don’t know anything about any players (including Damon’s) or, let’s face it, the sport itself; so, with all that combined, we watch the final game in a sort of blank numbness. Since that game lasts about twenty minutes—and since the escalation of the team’s skill accounts for most of the film’s latter half—that severely hampers our ease at fully enjoying the proceedings.

Invictus deserves credit for adding in a few mischievous lines for Mandela to keep him from merely being a boring saint, but other small details are botched. We don’t need the awkward quasi-hug between the antagonists-turned-somehow-friends after the winning game (an irritating sports movie cliché), or the astoundingly predictable sequence involving a young Black kid and police officers during the game, to which Eastwood cuts back too many times.

Surprisingly for a movie that takes its obscure Latin title from the William Ernest Henley poem from which Mandela drew strength while in jail, Invictus is nothing more than a conventional sports movie. There’s more about Mandela that’s interesting, obviously, but they chose to go in a different direction. Greatest credit should go to the actors, especially Damon, who nails his limited role and accent (there’s a locker room scene where he delivers an anti-inspirational speech with such restraint and focus it’s a shame it only lasts for a couple minutes). But otherwise, it’s a safe movie, a relatively competent one, and a relatively frustrating one.