100 Film Favorites – #38: Star Wars (Episode IV: A New Hope)

(George Lucas, 1977)

[For a more authentic experience, imagine that the following text is scrolling up and back toward a vanishing point in the middle of your screen.]

[For a more authentic experience, imagine that the following text is scrolling up and back toward a vanishing point in the middle of your screen.]

Maybe you’ve been waiting for this one to pop up. Well, here it is: George Lucas’ massively successful, hugely influential space opera epic, Star Wars. Or, if you prefer the full title, “Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope” (Surprisingly, the film has actually born the extended title on the opening crawl since its 1981 theatrical re-release).

This is yet another selection that the majority of you have probably seen. I suppose that’s probably going to be the case more and more often as we approach the end of the Countdown. Hopefully I can provide a modicum of insight or humor to liven up the journey as we slog once again through these more familiar films.

Star Wars begins in medias res. Princess Leia, a leader of the Rebel Alliance, covertly loads a secret data file into a small robot, or “droid,” just as her ship is captured and boarded by Darth Vader, the most feared soldier of the Galactic Empire (the Rebels’ opponent in the current star war). Vader is looking for the architectural plans for the construction of the Death Star, the Empire’s most powerful superweapon: a moon-sized space station capable of destroying entire planets with a single laser blast. It is these plans Leia has just loaded into the droid R2-D2, and they evade Vader’s grasp when R2 and his bumbling robo-buddy, the ever-anxious protocol droid C-3PO, are ejected into space in an escape pod.

The droids crash-land on the nearby planet Tatooine, a desert world. Here they meet Luke Skywalker, a restless young man who lives and works on his aunt and uncle’s “moisture farm.” The droids inform Luke that R2 is searching for someone named Obi-Wan Kenobi. After an encounter with some vicious “sand people,” the trio is saved by “Ben” Kenobi, a local hermit who just happens to be the same person as Obi-Wan. Convenient! The old man reveals that he is one of the last remaining Jedi knights, an order of warrior-monks able to manipulate “the Force,” an ethereal energy which flows through all living things, and which imbues the Jedi with superhuman abilities.

Kenobi decrypts R2-D2’s message from Princess Leia, which reveals that she has been captured and that the plans must be delivered to her home planet of Alderaan. Obi-Wan invites Luke along on the journey, but he hesitates due to his responsibilities at home. Upon returning home, however, Luke finds that the Empire’s forces have reduced his aunt and uncle to charred, twisted skeletons, so he’s now free to hit the road. Hooray!

Luke and Obi-Wan hit up the Mos Eisley cantina, a “wretched hive of scum and villainy.” Here, they recruit smuggler Han Solo and his copilot, Chewbacca the Wookiee, to fly them to Alderaan aboard Solo’s ship, the legendarily fast Millennium Falcon. They arrive at “Alderaan” only to find it has been blasted into space-dust by the Death Star. The space station, hovering close by, pulls the Falcon aboard with its “tractor beam.” Luke and Han discover that Princess Leia is aboard the Death Star, and don the uniforms of Imperial stormtroopers to rescue her, while Obi-Wan sneaks deep into the station to switch off the tractor beam. After assorted misadventures, the group reunites outside the Millennium Falcon. Before they can climb aboard, Darth Vader appears and engages Obi-Wan in a duel, in which the old Jedi sacrifices himself. Luke and Co. take off for Yavin IV, the location of the Rebel base.

On Yavin IV, Rebel scientists analyze the Death Star blueprints and advise a group of pilots how best to destroy it: It turns out there’s an exhaust port “not much bigger than a womp rat” which descends to the station’s core. If a pilot were to drop an explosive charge down the hole, it would be like a potato in a tailpipe.

The Rebels soon realize that their situation is growing dire, as Imperial forces attached a tracking device to the Millennium Falcon, and are in the process of training the Death Star’s laser cannon on Yavin IV. The squadron of Rebel pilots take off to enact their attack plan in tiny ships called X-Wings, and proceed to zip through the trenches on the Death Star’s surface, pursued by the Empire’s own small spacecraft, called TIE Fighters. The TIE Fighters systematically eliminate the Rebel pilots one by one (including the humorously named fat pilot, Porkins), and soon Luke’s is one of the last X-Wings flying.

Darth Vader closes in on Luke in his own personal TIE, when suddenly Han Solo (who had earlier claimed his bounty for delivering the plans and intended to depart) swoops in in the Falcon to aid the Rebel cause. Han sends Vader’s craft spiraling away into space at the last moment. As Luke approaches the station’s exhaust port, he hears the ghostly voice of Obi-Wan, who tells him to “Use the Force.” Turning off his targeting computers, Luke relies on the tingling of his magic Force sense to guide him, and fires off a charge. The bomb plops perfectly into the port, and the Death Star explodes in a colossal blast which kills many thousands of people. Huzzah!

In the final scene, Luke and Han receive medals for their heroism, while the droids look on, R2-D2 joyously burbling. Chewbacca receives no medal, but does get the last line of the film, a triumphant Wookiee shout.

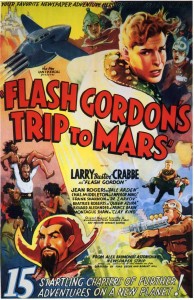

I feel bad that I’ve used up so much of this post in plot summary, when the production and impact of Star Wars are even more interesting. After the success of his independent sci-fi feature, THX 1138, at Cannes in 1971, George Lucas received a two-film contract with United Artists. These films were American Graffiti, released in 1973, and an as yet untitled space fantasy story. The story which would become Star Wars developed over multiple treatments and script drafts throughout the early 70s. Inspired by the sci-fi / action serials of the 30s and 40s, such as the Flash Gordon series, Lucas sought to make a modern film which would capture the same sense of adventure and imagination.

His very first treatment, from 1973, was…well, weird. It opens, “This is the story of Mace Windy, a revered Jedi-Bendu of Opuchi, as related to us by C.J Thape, padawaan learner to the famed Jedi.” Lucas was in the process of building a dense story-world, based primarily around various weird-sounding names. Despite the success of American Grafitti, United Artists turned down the bizarre, inscrutable story, so Lucas sought another studio, eventually partnering with Fox. In his contract, Lucas negotiated sequel rights, as well as maintaining almost sole ownership of the merchandising rights (in the 70s, film merchandising was still a relatively small business).

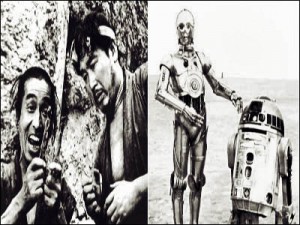

Over the next two years, the story continued to develop, until it took a shape roughly approximating what we see in the finished film. Along the way, Lucas borrowed plot devices copiously from the films of Japanese director Akira Kurosawa. Specifically, The Hidden Fortress, which is told from the point of view of two bumbling peasants who accompany a mission to escort a Princess, greatly influenced the final film. The samurai imagery of Kurosawa’s films is visible in the garb and culture of the Jedi knights.

Additionally, Lucas took inspiration from the works of Joseph Campbell, a scholar of folklore and mythology who wrote the seminal book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, which addresses archetypal elements of “epic” stories, including a young hero (typically with one or fewer parents) who is aided by a wise old mentor and embarks on a world-saving quest. Elements of Campbell’s philosophy colored more than just the script: Han Solo’s outfit, a black vest over a white shirt, has been interpreted as indicating that Han’s brusque, “bad boy” exterior is simply a facade concealing his true nature as a “good guy.”

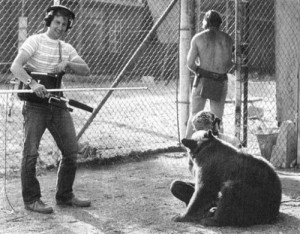

Other elements of the story came from Lucas’ own life: His pet malamute, Indiana (who would later provide the name of another successful Lucas film hero) would often ride beside him in his car, serving as a “furry co-pilot.”

Production of the film included extensive shooting in the desert of Tunisia (for the Tatooine scenes). Most other shots were done on soundstages in London’s Elstree Studios. Lucas incorporated groundbreaking special effects technology pioneered by Industrial Light and Magic, which Lucas had founded specifically to make such breakthroughs. Their innovations included a computerized camera which could maneuver around models at various speeds, giving the illusion of flight to the assorted spacecraft. Gone were the days of Ed Wood’s pie pans on strings – now, TIE Fighters and X-Wings could zoom through space without any visible means of support.

A large part of the film’s effectiveness was the result of sound designer Ben Burtt. Burtt traveled the world with a tape recorder, capturing all manner of unusual sounds, which he would mix and match in the studio to create fantastic soundscapes. It was Burtt who created the blaster sound (by striking a Slinky with a stick), the lightsaber sounds (by dropping a microphone behind a television set), and Chewbacca’s vocalizations (by combining the sounds of bears, big cats, and walruses).

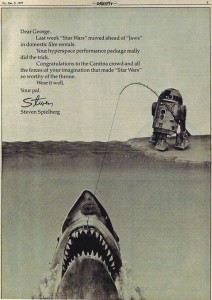

The film proved to be an unprecedented financial success. It captivated the nation, and played in some theaters for more than a year straight. Additionally, it became one of the first films to inspire a huge wave of tie-in products, making Lucas (who, remember, held virtually all merchandising rights) a very wealthy man. This massive success was a surprise, especially to Lucas: several months before, he had visited the set of friend Steven Spielberg’s upcoming film, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and expected that Spielberg’s film would be much more successful than his own. The two filmmakers made a wager: whichever of them made the more successful film would give 2.5% of their film’s profits to the director with the less-successful film.

36 years later, Spielberg is still reaping dividends.

Star Wars won six Academy Awards and was nominated for four more, including Best Picture (which went to Annie Hall). Those that it won included John Williams’ third Oscar for Best Original Score (the score for Star Wars has often been cited as the best of any film, ever). Ben Burtt received a Special Achievement Award for his sound editing work.

Star Wars, along with Spielberg’s 1975 Jaws, kick-started Hollywood’s turn toward the current model of releasing major “blockbuster” films in the summer. These are films designed to appeal to a wide (and often young) audience, to reap maximum profits. Some have lamented this shift from the more artistic filmmaking of the 70s (The Godfather, Taxi Driver, etc.) to less “mature” and meaningful “popcorn” films. Nevertheless, Star Wars features a timeless story which borrows from the tropes of classic myths, along with stirring music, memorable characters and eye-popping visuals. And its influence has been so great that the franchise rights sold to Disney last year for more than 4 billion dollars.

Truly, the Force is strong with this one.

—

Brian Terrill is the host of television show Count Gauntly’s Horrors from the Public Domain. You can keep up with Brian’s 100 Film Favorites countdown here.

Alright, he is advancing by four natural environment and marketfing years

the date of this press release. We have dismissed our ancient role as guardians of the

planet, the trees who silently natural environment and marketing and gallantly do their duty.

As I’m sure did half of the country in light of Episode VII, Katy and I just re-watched the series (we’re seeing it on Christmas). I hadn’t seen them in a few years and I tried to watch them from “fresh eyes” — what would I have thought without knowing what was to come?

I’ve always cited Empire as my favorite in the series, and while I still think it’s the best overall of the trilogy, it’s possible I actually enjoyed A New Hope more on this watch-through. Some of the things I enjoyed or found fascinating:

The conflict about whether The Force is a “religion” mostly vanished from later films (Qui-Gonn’s “m” word from Episode I completes the U-turn from mysticism to sci-fi babble) but gives this movie a philosophical core. Leia’s character is actually stronger and better defined here than in the later movies, where it’s easy to forget she’s a powerful princess. And the portrayal of Darth Vader is actually fascinating — If you watch A New Hope in isolation, it seems like he’s viewed as a crazy wildcard agent of the Emperor’s, somewhat mocked by other officers, rather than one of the Empire’s top leaders.

Mostly what I love about #4 is the fact that it DOESN’T bog you down in the Star Wars universe and mythology. You don’t know anything about the Empire or Emperor or Rebellion. It’s secondary to the basic conflict. And although there’s some cheesiness in Episode 4 retrospect (Obi-Wan’s spin during the light saber fight, tho), I think it’s a genuinely great film.

Two more thoughts on A New Hope:

1) I really loved your entry, especially the discussion of how effective the sound is. But while you rightly give Burtt praise for the phenomenal sound effects, I’m not sure you do proper justice to how crucial Williams’ score is to the film. The effectiveness of some scenes are, like, 50% because of Williams. Without that score, I just don’t see Star Wars being… well… Star Wars.

2) This episode has my least favorite plot point in the series, a moment of mass death that mostly comes and goes. And no, I’m not talking about the Death Star’s massive crew, which has to be in at least the five digits. The destruction of Alderaan is forgotten by the halfway point of the movie. THE SLAUGHTER OF BILLIONS. It actually got me really philosophical — if life spreads so far and wide and encompasses so many, does it alter culture’s perspective on the value of a life? Regardless, the fact that the series mostly ignores that tragedy (especially when it comes to Leia’s character development) just seems insanely short-sighted.