“Where the hell are they?”

“The appropriate question is, when the hell are they?”

-Marty & Doc, Back to the Future

If you’ve read many of my articles here on EarnThis, there’s a good chance you already knew that Brian Likes this one. Of the hundred entries in my Film Favorites Countdown, fully 10% include some variety of time travel (if you count the time-loop in Groundhog Day and Galaxy Quest‘s time-rewinding “Omega 13” device). I even pontificated on the appeal of the time travel concept in the “Books” entry of this series:

“The chance to re-live our past or peer into, and perhaps alter, our future ranks among the most tantalizing prospects in all storytelling.”

Want to win the lottery? Fix your mistakes? Meet the great figures of the past? Learn the legacy you’ll leave behind, then change it? All are possible in the wide world of time travel literature. Add to that list “destroy the universe through a series of brain-bending paradoxes” and you’ve got a subgenre which is endlessly compelling, complex, and, quite frequently, confusing. These are stories of anywhere and anywhen that dare to dream of a day when mankind might not be held in lock-step with time’s forward march.

So without further ado, let’s set the Wayback machine for 1888 and take in a brief history of history-hoppers.

#1. Looking Backward

(Edward Bellamy, 1888)

“With a tear for the dark past, turn we then to the dazzling future, and, veiling our eyes, press forward. The long and weary winter of the race is ended. Its summer has begun. Humanity has burst the chrysalis. The heavens are before it.”

One of the earliest examples of “true” time travel in literature, Looking Backward: 2000-1887 tells the story of Julian West, an 1880s Bostonian who resorts to hiring a hypnotist to combat his insomnia. Each night the hypnotist puts him to sleep, and each morning returns to awaken him. Then, one morning, the hypnotist fails to return. And because Victorian-era writers didn’t really understand how hypnotism works (not that we know all that much more now), the “sleeping” West remains in a state of suspended animation. His house eventually burns down, and his neighbors and family assume him dead, though West is actually “slumbering” in his specially-designed soundproof cellar. Finally, he awakens 113 years after “going under,” to find himself in the distant future of 2000 AD.

Bellamy’s novel is really primarily a socialist manifesto, and one of the first books to popularize socialist ideas among English-speaking readers. The “narrative” consists almost entirely of exposition, as Dr. Leete (West’s guide to the world of tomorrow) explains precisely how his perfect socialist society functions. In Bellamy’s utopian vision, virtually all aspects of life are state-controlled, so as to ensure equality: “the nation is the sole employer and capitalist.” Eliminating the possibility for economic inequality also eliminates greed, envy, and a majority of the world’s crime (Leete states that all crime not spawned by inequality is the result of “atavism,” a medical term of the 19th century which held that certain people were genetically prone, a la McTeague, to committing crimes).

The good doctor goes into detail describing many aspects of 21st century life: Citizens receive newfangled devices known as “credit cards” which they use instead of money to acquire goods and services. Everyone receives the same amount of credit each year – those with particularly hard or unpleasant jobs simply have to work fewer hours. Copyrights have been abolished, and artists and writers petition the government to undertake new projects, at which point completing a given project becomes their job. Everyone retires by 45.

I gotta say, Bellamy’s vision for a perfect world under socialism failed to win me over, but the same can’t be said of many Americans of the time. Looking Backward was an instant phenomenon, and inspired the founding of more than 100 “Bellamy Clubs” nationwide, several of which evolved into full-fledged socialist communes. Countless writers wrote unofficial “sequels” to the novel…or rather, rebuttals or reaffirmations of Bellamy’s theses, which barely constitute a “novel” in the first place.

Tidbit: In addition to credit cards, Bellamy also predicted the advent of radio (although the system described in the book works by cable rather than broadcast “over the air”).

#2. The Time Machine

(H.G. Wells, 1895)

As inventor of both the time machine and the alien invasion, H.G. Wells has left a tremendous influence on the cultural imagination and the field of science fiction. While his sci-fi was never particularly “hard” (realistic or based on actual research), there’s no doubt Wells’ imagination could captivate the masses. And besides, as he tells Jules Verne in a great moment in the retired Disney World attraction The Timekeeper, Wells went time-traveling “every bit as often as Verne traveled 20,000 leagues under the sea.”

“The Time Machine” tells the story of an unnamed Victorian inventor, who creates…well, a time machine. Duh. One evening, the Time Traveler bids farewell to his skeptical friends at a party and departs for the far future. Like, really far. He arrives in the year 802,701 and emerges to find the world radically changed. The land is covered with lush greenery, and the people of the era, an elfin race known as the Eloi, live an apparently idyllic life of luxury. But as he spends time with them, the Time Traveler begins to notice problems with the Eloi’s “paradise.” You see, the Eloi, while beautiful, are utterly vapid. They lack curiosity and ambition, and care nothing for intellectual pursuits. The Time Traveler supposes that this development must be the end result of human evolution: with no more disease, war , or other hardships to overcome, humankind has grown complacent to the point of indolence.

But the worst is yet to come. The Time Traveler gradually discovers that the Eloi aren’t our only 8,028th Century descendants. Instead, humanity has branched into two races, so different as to perhaps be distinct species: the beautiful but simpleminded Eloi aboveground, and the industrious yet animalistic Morlocks below. The Time Traveler deduces that the Eloi/Morlock dichotomy is simply a further-advanced version of the class disparity at work in his own (and our) time. While the wealthy and contented bourgeoisie gave rise to the Eloi, the oppressed laborers of the lower classes became the beastly Morlocks. Now, the Morlocks spend their days toiling amidst subterranean machinery (it’s suggested that they are the ones keeping the greenery fresh and bountiful), emerging only at night to harvest their food…the Eloi themselves.

The novella is structured somewhat oddly, in that the main thrust of the story is resolved fairly quickly. The Time Traveler successfully snatches his machine from the clutches of the Morlocks, and makes a getaway through time. But rather than returning home, the third act of the story sees the Time Traveler heading even further into the future. He witnesses the sun growing into a red giant and baking the Earth to a worldwide desert, and strolls the cracked dirt observing the last meager forms of life. After this apocalyptic sidetrip, the Traveler finally does return home, where he presents his incredulous friends (after all, from their perspective he’s only been gone a brief while) with a bizarre flower given him by the Eloi.

The story ends with Filby, the Time Traveler’s closest friend, recounting how the Traveler only stuck around a week before taking another jaunt into the future…from which he has never returned. From time to time, Filby says, he ponders the strange flower, wondering whatever became of his friend.

The Time Machine served as the prototype for countless time travel stories to come. It introduced (surprise surprise) the concept of a vehicle-like “time machine,” piloted by a “time traveler.” The only major hallmark of the time travel “genre” missing here is manipulation of the past and/or rampant paradoxes.

Owing to this formative influence, Wells’ novella has inspired numerous adaptations, take-offs, and sequels. The story has been made into two feature films:

The 1960 version (from 7 Faces of Dr. Lao director George Pal) features some remarkable special effects for its time, and introduced one of the most iconic time machines in all film (it would not be eclipsed until the arrival of Doc Brown’s Delorean a quarter century later).

In an early episode, the “Big Bang Theory” guys purchase the authentic George Pal time machine on ebay.

The 2002 version is a mixed bag for me, and probably deserving of a longer analysis than I’ll give here. Suffice to say that, while not a great film, it’s better than I expected, and worth a watch for time travel fans. Interestingly, this version was directed by Simon Wells…great-grandson of H.G. himself. The highlight for me was the final shot, in which the Time Traveler (who remains in 802,701) stands thoughtfully on a patch of land which was once his house. 5 feet and eight hundred millennia away, Filby stands “beside” him in the parlor, also lost in thought.

Over and above its formative influence, The Time Machine has stuck with me for one major reason:

Morlocks are terrifying.

I’ve been scared of Morlocks since I first saw “Bark to the Future,” the Wishbone take on Wells’ story. But even scarier than the Morlocks’ hideous, simian appearance is their seeming inevitability. The dichotomy predicted by Wells, though rooted in 19th century socialist ideas much like Bellamy’s, seems every bit as prescient today: The divergence between beautiful sun-dwelling people and ugly, technically savvy “basement-dwellers” is growing ever faster in our “internet age.” One of my greatest fears is that I won’t be able to break the cycle, and my descendants, if any, will continue down the Morlock path.

And yet here I sit, blogging.

Total Morlock move.

#3. Time After Time

(Nicholas Meyer, 1979)

Now let’s abruptly jump forward 84 years (this “history” is far from comprehensive, but at least it preserves the time-hopping style to be expected of the genre). Time After Time stars Malcolm McDowell as H.G. Wells – in this interpretation, The Time Machine is autobiographical. At a dinner party similar to the one in the novel, Wells demonstrates to his disbelieving guests a time machine of his own design. One of Wells’ friends, an esteemed doctor, is especially intrigued.

Suddenly, the police burst in, and reveal that “Dr. John” is none other than notorious serial killer Jack the Ripper. The Ripper escapes the clutches of Scotland Yard by leaping into the time machine and departing for the distant future of 1979.

Wells is dismayed that the Ripper is now loose in the future, which he imagines, after all, to be a socialist utopia. Luckily, the time machine is designed to return to its time of origin, and so “H.G.” takes it upon himself to follow the Ripper to 1979 and bring him to justice.

So now you have a Victorian era time traveler chasing a Victorian era serial killer, against the funky fresh backdrop of the 1970s. Who could ask for anything more?

Wells finds the “brave new world” of the 70s to be less than utopian. In a memorable “villain monologues about the appeal of his worldview” scene, Jack the Ripper muses that the modern world, with the ubiquity of warfare and violent media, is perfectly suited for people like him: “The world has caught up with me and surpassed me. Ninety years ago I was a freak. Now I’m an amateur.”

Wells wants to return with the Ripper to their own era. The Ripper wants to take possession of Wells’ time machine key, which will enable him to keep the machine from hopping without him. Meanwhile, he resumes his murder spree. Into the middle of it all stumbles Amy Robbins (Mary Steenburgen), a bank-teller who initiates a romance with Wells (he is impressed at the progress made by the “women’s lib” movement). In a not-so-progressive move, she manages to get captured by the Ripper, who plans to use her to bargain for the machine key.

Wells begrudgingly hands over the key, but performs a bit of Rocketeer style last-minute sabotage. As the Ripper climbs into the machine to make another escape, Wells yanks off the “vaporizing equalizer.” The Ripper launches into the future…but the machine is left behind, dooming him to hurtle through time forever without a means of stopping.

If you ask me, this time machine has some serious design flaws.

If you ask me, this time machine has some serious design flaws.

In the end, Wells convinces Amy to return with him to the Victorian period, and pre-credits text reveals that Amy Robbins really was the name of H.G. Wells’ second wife. That their courtship really involved time-jaunts to 1970s San Francisco, however, seems more historically dubious.

Tidbits: Nicholas Meyer’s film was an “adaptation” of his friend Karl Alexander’s novel of the same title. Unusually, though, the novel was being written at the same time the film was being produced. The director and the author collaborated on the story, and the two “Time After Times” were released in quick succession in 1979.

-Mary Steenburgen must have a thing for time travelers: She would later play Clara Clayton, Doc Brown’s love interest in Back to the Future, Part III. -Speaking of Back to the Future, the date which H.G. Wells both departs from and arrives at is November 5th…the same date Doc Brown conceived of the flux capacitor and Marty arrived in the 50s. What’s the connection? Do all time travelers secretly idolize Guy Fawkes? -Steenburgen and McDowell really did fall in love during production of the film, and were wed soon after. They stayed married until 1989, when I imagine production of BttF 3 drove them apart, a jealous McDowell unable to stand the sight of his wife in the arms of another time traveler.

-Steenburgen and McDowell really did fall in love during production of the film, and were wed soon after. They stayed married until 1989, when I imagine production of BttF 3 drove them apart, a jealous McDowell unable to stand the sight of his wife in the arms of another time traveler.

#4. Welcome to the Terror-Go-Round

(A.G. Cascone, 1997)

Now here’s one that’s pretty offbeat. The “Deadtime Stories” series was a 17-installment Goosebumps knockoff penned by “A.G. Gascone” and published between 1996 and 1997. Like R.L. Stine’s more successful franchise, the books feature child protagonists contending with sinister supernatural threats.

I would never have heard of the series at all had I not received this particular volume in a literal garbage-bag-full of similar juvenile paperbacks handed down to me by my slightly older next door neighbor (I was perhaps 9, he 12). Welcome to the Terror-Go-Round revolves around two siblings who sneak out one evening to attend a traveling carnival which has set up shop on the outskirts of their town.

The main conflict of the story sees the kids trying to evade the clutches of “Arboc,” the carnival’s snake-like ringleader, and his retinue of sideshow freaks, former carnival-goers whom Arboc has trapped and mutated. But far more interesting, and the motivation for including Terror-Go-Round on this list, is the book’s fairly novel take on time travel. The “Terror-Go-Round” of the title is a carousel at the center of the carnival which also functions as an unusual time machine: It can deposit riders at any point in time and space where the carnival has stopped. It is by making one of these time-jumps that the siblings first arouse the attention of Arboc and his cronies. As in A Christmas Carol, Terror-Go-Round time travelers cannot be seen by the inhabitants of the periods they visit. Nevertheless, the kids can be seen by Arboc and the freaks, who, like the carnival, seem to persist throughout the ages without growing any older.

The ending is where Gascone’s story really shines. As might be expected, the kids eventually succeed in freeing the freaks and outsmarting Arboc, and finally return home aboard the Terror-Go-Round. But there’s a twist. On one carousel-stop roughly halfway through the book, the siblings accidentally interrupt a teenage couple on a date, bumping the boy’s arm and causing him to spill his soda on the girl. While the boy sputters an awkward excuse (remember, the time travelers are invisible), the girl storms off. After this apparently irrelevant episode, the “main” story arc returns to the forefront.

Fast-forward to the end of the novel, with the victorious children returning home. The siblings enter their house, calling joyfully to their mom and dad…only to find that, while their mother does live there, she has a different husband and another set of children. The kids gradually put the pieces together: Their parents’ first date had been at a carnival. THE carnival. And it was this very date which the kids ruined in their time-jumping. Thus, they inadvertently prevented their parents’ getting together, Back to the Future style, albeit without a Doc to point out the error.

Now the children have no home and no family, as well as no real identity, as no one else remembers them having ever existed.

THE END.

That’s got to be the bleakest ending since the finale of Dinosaurs, in which the protagonist accidentally brings on the extinction of his entire species, and then has no choice but to huddle fearfully beside his family, awaiting death.

(Michael Crichton, 1999)

Like many of Michael Chrichton’s other novels, Timeline combines elements of the action genre and a given branch of contemporary scientific research: In this case, quantum physics and multiverse theory. The story follows a team of archaeology students conducting an excavation in Dordogne, France, the site of a battle between adjacent English and French settlements during the Hundred Years’ War. In true Chrichton form, the dig is being funded by a sinister tech corporation. Eventually the professor leading the study grows suspicious of the company’s interest in the Dordogne site, and he decides to pay a visit to the corporation’s headquarters.

Here’s where the time travel comes in. Almost immediately upon the professor’s departure, the students unearth a parcel containing his eyeglasses and a note in his handwriting…both of which show evidence of being more than 600 years old. The note reveals that the professor has been transported to the year 1357 by ITC, the corporation sponsoring the dig.

The students travel to ITC headquarters, where founder Robert Doniger (a very John Hammond-like figure) explains that his company is a physics research firm, and they have succeeded in creating a type of time travel by manipulating the tiny perforations in the subatomic “quantum foam” which serves as the “fabric” of space-time, holding our universe together and forming a membrane between it and others. They have managed to create portals to a number of points in time and space throughout world history, one of which happens to be the Dordogne region on the eve of the decisive 1357 battle between the English village of Castelgard and the French town of La Roq. It is against this backdrop that the students (accompanied by a few ITC lackeys) are sent to rescue their professor, Back to the Future III style, and return him to the present. Like the Time After Time machine, the ITC device is set to pop in and out at given times, and so the team has only a limited window in which to complete their mission.

Most of the book follows the trials and travails of the time travelers as they’re bounced around from side to side of the impending combat. They are taken aback to find that the knights on both sides are thuggish fighters, far more bloodthirsty than the “shining armor” image of their legacy would suggest. And all the while, courtly intrigue abounds. Alliances are forged and betrayed, secret pasts are revealed (one of the more malicious knights is actually a time traveler left behind by ITC’s last voyage), and there’s even time for a bit of Shakespearean cross-dressing.

Scenes in 1357 are interspersed with those set in the present, as ITC techs and a student who stayed behind struggle to fix the time machine’s “landing pad,” which has (of course) been accidentally destroyed in an unforeseen explosion and must be repaired before the time portal can reopen. While they work, Doniger reveals his ultimate goal behind the ITC project. Essentially, he wants to use the past as a tourist destination, for no real reason. Seriously, time tourism is a terrible idea, and Doniger doesn’t really explain his motivation, beyond simply wanting money. Jurassic Park I understand. This, not so much.

That said, Doniger’s fate at the end of the novel seems a little harsh, even if does provide the book’s most memorable scene: After the surviving time travelers make it back to the future (though one opts to stay behind and live in the middle ages), they seize Doniger, lock him in the machine, and fire him off into time. However, instead of arriving in 1357, Doniger finds himself in 1348…just after the onset of the Black Death in Europe. The penultimate chapter ends with the words, “and he began to cough.”

The novel itself ends with the students returning to their dig, where they find the grave of the friend who stayed behind. The inscription tells how he lived out a prosperous life as a noble, and ends with a message to his future-friends:

“Companions whom I loved, and still do love, … tell them, my song.“

Timeline was adapted to film in 2003, with regrettable results. While it does follow the general arc of the book, there are two things that I hated, hated, hated about the movie:

-First off, the ITC scientists in the film state that the portal to 1350s France is the only one they’ve managed to open. This limitation removes much of the potential coolness of the novel, which suggested that any time or place could be accessed via the proper input code. It also eliminates two of the story’s coolest moments: An early aside in which disobedient ITC employees are threatened with banishment to the times and places of historical cataclysms (Pompeii, 79 A.D., for instance, or Tunguska in 1908), and Doniger’s aforementioned demise.

-Second, time travel in the film is presented as fully predeterministic. In other words, things are destined to happen a certain way, because they already have. Whatever actions the time travelers take in the past will have no influence on the fate of the future, because the time-trip is already part of the “set” timeline. As I’ve written before on my Brian Terrill Movie Night page, predetermination time travel is my least favorite variety, and I wonder why it’s so frequently used in fiction. If characters’ actions can ultimately have no effect on their fate, why should we care about them? Not to mention that, if we already know how things are going to pan out and there is no chance of a change, all the tension is thrown out the window. There are no “stakes.” In the Timeline novel, Chrichton never fully comes down on one side or the other of the predetermination issue: the professor’s note and the straggler’s grave are only found after their respective time-trips are made, suggesting that they could represent changes to the “original” timeline. In the film, however, the students are already in the process of excavating the tomb when the story begins, though only after they return do they discover it to be the grave of their friend.

Tidbits: Greek fire, a mysterious ancient weapon apparently similar to napalm, is awesome, and I learned about it here, when the professor offers to concoct some for his medieval captors in order to spare his life.

(Shane Carruth, 2004)

In 2004, an independent filmmaker took $7,000 and turned a headache into a movie.

Primer, often billed as the “smartest time-travel movie ever,” follows Abe and Aaron, a pair of young physicists dabbling in fringe experiments. Their physics prowess must not be all that great, however, because their prototype for an anti-gravity machine actually turns out to be a time machine.

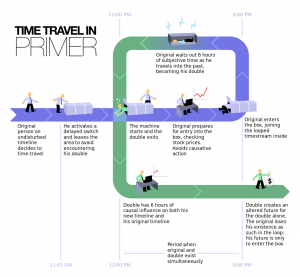

The Primer time machine, referred to throughout the film simply as “The Box,” works by a unique set of “time travel rules”:

-The prospective time traveler switches The Box on at his desired arrival time. Say, noon.

-At a later time, the traveler switches The Box off and climbs inside. Let’s say 6:00 pm. Now, the traveler waits inside the box for six hours, while the time field inside the box “proceeds” backward.

-The traveler emerges from the box at noon. Now the traveler exists as a duplicate of their original self, currently waiting to climb into the box at 6.

Okay. You got all that? So a traveler can only go back in time, and only as far as the point at which the box was switched on. Seems pretty simple, right?

Well, not for long. Abe and Aaron both set up “fail-safe” machines before they officially begin their trials, each without telling the other. These fail-safes are intended to allow the travelers to undo any potential paradoxes by going back to an earlier time than permitted by the “official” boxes, thus undoing their actions.

Scratching your head yet?

Things only get more complicated when Aaron builds a collapsible “Box” which he then takes back in time with him inside another one of the other machines. Before long, Abe and Aaron are fighting (both each other and their time-duplicates), attempting to maintain a Groundhog Day-style “perfect” iteration of their ever-repeating week, and bleeding from their ears (a time travel side-effect also addressed in Timeline).

As it so often does, XKCD captures the situation accurately:

Alternatively, if you REALLY want to understand this convoluted chronicle of chrononauts, you can either watch the film itself many times, or watch this helpful walkthrough, which “deobfuscates” the movie step by step…for a full fifteen minutes.

Alternatively, if you REALLY want to understand this convoluted chronicle of chrononauts, you can either watch the film itself many times, or watch this helpful walkthrough, which “deobfuscates” the movie step by step…for a full fifteen minutes.

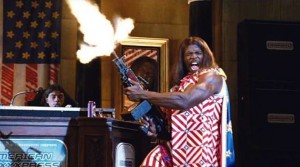

#7. Idiocracy

(Mike Judge, 2006)

“As the 21st century began, human evolution was at a turning point. Natural selection…which had once favored the noblest traits of man, now began to favor other traits.”

Mike Judge’s Idiocracy is a dystopian satire based on the premise that, in a world without predators, pandemics, or other major challenges to overcome, human evolution will come to favor stupid people (who reproduce abundantly) over intelligent (ergo, cautious and sexually prudent) people. This premise is perfectly introduced in the brilliant 3-minute opening scene.

Protagonist Joe Bauers (Luke Wilson) is a military officer selected for a secret experiment in suspended animation. Chosen for being “perfectly average,” everyman Joe is sealed in a tank and, Bellamy style, is promptly forgotten when the officer overseeing the project is arrested. 500 years later, Joe (along with another test subject, a woman named Rita) awakens when a mountain of garbage collapses and dislodges his capsule.

By 2505, the “dumbing down” of America has progressed to such an extent that snack-food corporations run the government, TV programming consists almost exclusively of ads (with a smattering of porn), and the year’s Best Picture winner is “Ass, Farting.” While Looking Backward had its Dr. Leete showing the protagonist the wonders of the future, Joe is similarly guided through the land of “idiocracy” by Frito Pendejo, a stone-stupid 26th-century “everyman.”

When an IQ test shows Joe to be the most intelligent man in America, he is recruited by President Camacho (“Old Spice Man” Terry Crews) to serve as Secretary of the Interior and hopefully solve the country’s crippling agricultural problems. It doesn’t take Joe long to discover that the nation’s crops are irrigated not with water, but with “Brawndo,” a Gatorade-like sports drink. This is because the Brawndo corporation (which owns the FDA and the FCC) assures everyone that their product “has what plants crave.” After some investigation, Joe learns that what Brawndo “has” is electrolytes…in other words, salt. Joe swaps the earth-salting equipment with a water system, and once crops begin to grow again an overjoyed President Camacho promotes him to Vice President.

With no time machine to take them home, Joe and Rita remain in the future. They go on to wed and have three of the world’s smartest children…while Frito and his eight wives have 32 of the world’s stupidest.

Idiocracy is simultaneously both a bleak and hilarious portrayal of America’s faltering intellectual standing. While the central premise has its weaknesses (if a population really did become “too stupid,” some threat would eventually wipe them out, as the crop shortage in the film very nearly does), the film certainly feels chillingly spot-on. And in spite of the very low-brow culture it depicts, the film feels surprisingly high-brow: Its arguments against consumerism and anti-intellectualism could be straight out of a 19th century story by Wells or Bellamy. Indeed, Idiocracy‘s unthinking populace of 2505 isn’t all that different from Wells’ vapid Eloi.

Here’s hoping we can stave off the great “dumbing down.” We at Earn This do our part to further thoughtful film criticism – At least for the moment, we still “want to know whose ass it is, and why it’s farting.”

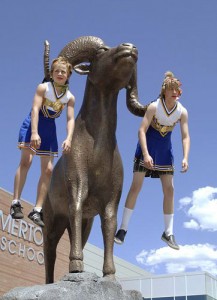

#8. Minutemen

(Lev L. Spiro, 2008)

Okay, I admit it. I watched a LOT of television in my senior year of high school. My family had finally gotten cable, and I simply left the TV on while doing other things. While almost undoubtedly unhealthy, this binge gave me one great gift: a comprehensive knowledge of “DCOMs,” or Disney Channel Original Movies. These are TV movies produced for the Disney Channel, and roughly 4 to 6 are released each year (though earlier TV movies are sometimes included, the official “DCOM” designation first appeared in 1997). While aimed squarely at a “tween” demographic, some of these films aspire to a wider audience. A few actually deserve it. I can’t say for sure if “Minutemen” is among them. But I enjoyed it.

The story begins on the first day of high school. When Virgil, a freshman, stands up for Charlie, a nerdy prodigy who inadvertently disrupts football practice when his experiment in rocketry goes awry, both boys become the victims of a humiliating prank. Forced to wear cheerleader outfits and strung up in front of the school, Virgil and Charlie become school laughingstocks.

Three years later, the boys, still outcasts, are poised to begin their senior year. When Charlie announces offhandedly that he has drafted blueprints for a time machine, Virgil sees the potential to finally gain some social (and conventional) capital. The boys recruit Zeke, a mechanically-minded student, to help them construct the machine. They reserve a room in the school basement (as the “Back to the Future Fan Club”) and begin their experiments.

In their first mission, the “Minutemen” travel to the following day, in order to learn the winning lottery numbers. Returning to the present, they attempt to buy a ticket, only to remember too late that they are too young to do so. They convince a “living statue” street performer to buy the ticket for them, but upon winning the jackpot he simply skips down, leaving the boys none the richer.

Next the time-traveling trio focus on a seemingly more noble goal: fixing their fellow students’ social faux pas by granting them do-overs. Soon, the mysterious “Snowsuit Guys” (as in Back to the Future, time travelers “come in cold,” and so must bundle up in warm clothing) are the heroes of the school, preventing the kinds of embarrassments which they themselves had faced.

But their newfound fame spawns conflict: The kids the Snowsuit Guys have helped start to become big-for-their-britches douchebags; Virgil’s popular friend (already a douchebag) deduces Virgil’s identity and begins blackmailing time-favors; the FBI starts trailing Charlie (he stole some NASA files to complete his time travel schematics); and, worst of all, the boys’ time-hopping has caused the space-time continuum to become increasingly unstable.

But their newfound fame spawns conflict: The kids the Snowsuit Guys have helped start to become big-for-their-britches douchebags; Virgil’s popular friend (already a douchebag) deduces Virgil’s identity and begins blackmailing time-favors; the FBI starts trailing Charlie (he stole some NASA files to complete his time travel schematics); and, worst of all, the boys’ time-hopping has caused the space-time continuum to become increasingly unstable.

The film’s climax comes at the school dance. Which is 1950’s-themed. Honestly, I think the main reason I like this movie is for all the Back to the Future references. At any rate, a black hole begins opening outside the school, and the Minutemen step forward and admit their role in creating the time-tear. They hurl themselves into the black hole (kind of a weird choice) and, instead of dying horribly, they find themselves once again on that fateful first day of freshman year. Virgil intends to intervene and prevent his humiliation, but Charlie stops him. Charlie says that while Virgil has spent his high school years loathing the day in question, it has always been Charlie’s favorite day, as it was the day he made his first friend. Moved, Virgil allows things to play out as before. Instead, the boys take precautions to prevent themselves from inventing the time machine in the first place. World-ending crisis averted, the three travelers breathe a sigh of relief. Then Charlie unveils his latest project…a teleporter.

Minutemen isn’t perfect, but it’s better than any story about characters navigating the politics of high school popularity has a right to be. The film admirably captures a “Calvin and Hobbes”-style feeling of childhood adventure. Making a time machine with your friends will always be a cool idea.

Plus there’s Back to the Future references and the principal from Phil of the Future and Community. How can you go wrong?

Plus there’s Back to the Future references and the principal from Phil of the Future and Community. How can you go wrong?

(Felix J. Palma, 2008 [English translation 2011])

Even 30 years after Time After Time, H.G. Wells is still chasing Jack the Ripper. In this mammoth novel (some 600+ pages), three tales of Victorian-era time travel unfold and interweave. In one, a young man attempts to use time travel to save his girlfriend Mary Kelly from the Ripper’s clutches. In another, a progressive woman takes a vacation through a time tourism agency, and is surprised to find herself falling in love with the John Connor-like savior of the human race during the “automaton wars” of the future. And in the final thread, H.G. Wells himself, who has served as something of a “time travel consultant” in the first two cases, ponders the implications and limitations of time travel, particularly in literature.

I know they say not to, but I judged this book by its cover. See how cool it looks?! A mysterious man with a top hat and pocket watch? Something about steampunk and time travel? Sign me up! Such was my thought process when I first found a copy of The Map of Time in an airport book shop.

It wasn’t worth the inflated airport price. My biggest sticking point with this book is that, despite the fantastic nature of the cover illustration (and the description on the back) the story itself is surprisingly based in realism, almost to the point of cynicism. When I pick up a book about Victorian time travel, I damn well expect some outlandish steampunk hijinks.

And above all, I absolutely expect some ACTUAL TIME TRAVEL. But this book delivers none. Or at least, not the wacky, world-warping kind I wanted. Two of the stories involve time travel which is flat out fake. In the case of Mary Kelly’s boyfriend, his friends convince H.G. Wells to help them re-stage the scenario just prior to Kelly’s murder, so that the man can intervene, become a hero, and thus stave off his depression and avoid suicide. Hooray?

The time travel agency is a fraud too, albeit a bit more compelling. The man behind the scheme, a Barnum-like humbug, was for me the novel’s most memorable character. His smoke-and-mirrors conversion of a warehouse into the battlefield of a Terminator-esque robot war was fun to imagine even in spite of the lack of actual time travel.

The final act of the story is the closest the book comes to real time travel. In a cerebral segment, H.G. Wells stumbles across a “working” time machine. A lengthy description details how he uses it to explore and affect the future. However, the inherently paradoxical nature of time travel eventually causes Wells’ trip to undo itself, and thus never to have happened in the first place. The narrator suggests that this self-cancelling will be the result of anything Wells attempts.

Well, that’s a bummer. I thought for sure I’d find some time travel in my time travel novel.

If you absolutely must read this book, find it at the library.

Tidbits: Palma followed up the book with a sequel, “The Map of the Sky,” which again features H.G. Wells as a protagonist and involves elements from Wells’ The War of the Worlds. I’m willing to bet it doesn’t include a single alien.

-In addition to the Terminator elements, the book’s middle segment includes my favorite reference in the novel. In the mock history lesson presented by the “time tourism” huckster, one of the earliest automatons is said to have been “Dr. Phibes,” a chess-playing mannequin similar to the real-life “Turk“. As you’ll recall, the abominable Dr. Phibes of B-Movie fame was a fair hand at crafting automatons, such as his tin toy band, the “Clockwork Wizards.”

(Steve Pink, 2010)

I realize I’ve just endorsed a Disney Channel Original Movie and a Goosebumps ripoff, so my critical recommendation may not hold much sway at the moment. But if you take one thing away from this behemoth of an article, make it this:

Hot Tub Time Machine is a good movie.

Far better than the title might suggest.

In the story, three middle-aged losers (along with one of the men’s 20-something nerd nephew) take a trip to a ski resort in the mountains, hoping to recapture some of the lost glory of their youth. Though the hotel has fallen into disrepair, at least the hot tub still works.

The men’s drunken pity party gets a little out of hand when one of the friends pulls out a can of “Chernobly,” an “illegal Russian energy drink” similar to 4Loko. It’s not long before someone abentmindedly bumps the can, upending it and spilling the contents into the hot tub’s control panel. The combination of mysterious chemicals and electricity transforms the once conventional hot tub into – you guessed it – a hot tub time machine.

The men awaken in 1986, and find the resort returned to its heyday. Though they still see one another in their “old” bodies, to everyone else the travelers appear as they did in the 80s (save for the nephew, who wasn’t born yet; he just looks the same for some reason).

At first, the men are wary of causing paradoxes, and attempt to keep events “on track,” unfolding just as they did “the first time around.” This mindset gives rise to my favorite sequence in the film. In the present, the resort bellhop (played by Back to the Future‘s Crispin Glover) has only one arm. In 1986, he still has both. Thus, the men keep following the bellhop, using him as a gauge to determine whether events are still unfolding normally. In a series of cartoonish moments, Glover comes comically close to losing his arm, only to have the men gasp in dismay when he repeatedly saves himself at the last moment.

At first, the men are wary of causing paradoxes, and attempt to keep events “on track,” unfolding just as they did “the first time around.” This mindset gives rise to my favorite sequence in the film. In the present, the resort bellhop (played by Back to the Future‘s Crispin Glover) has only one arm. In 1986, he still has both. Thus, the men keep following the bellhop, using him as a gauge to determine whether events are still unfolding normally. In a series of cartoonish moments, Glover comes comically close to losing his arm, only to have the men gasp in dismay when he repeatedly saves himself at the last moment.

Ultimately, however, the time travelers come to see their unexpected trip as a chance to change their lives for the better, which they proceed to do. When at last they return to the present, the men find their situations much improved: happy relationships, a two-armed bellhop, and even wealth (like in Timeline, one friend opts to stay behind; In the interim he uses his knowledge of the future to found Google).

I went into Hot Tub Time Machine not expecting much, but it pleasantly surprised me. Sure, it’s all rather silly, but there are good laughs to be had throughout (particularly the inspired bits of physical comedy with the bellhop). More than that, I felt myself caring about the characters, and their time adventure is surprisingly compelling considering its hot-tub-based nature.

I for one am psyched that Hot Tub Time Machine 2 is due out this Christmas.

****

Phew. That was a long one. Hopefully it was a good use of your time. For now, at least, we’re all stuck traveling through time at the same rate: Forward, at one second per second. And, barring near-light-speed travel, that isn’t likely to change in the near future.

How lucky we are, then, that the silver screen and the printed page can transport us to any time and place.

And where we’re going, we won’t need roads.

I really enjoyed this one. I read the whole thing, too!

HTTM is great, as are most things that include “Dan’s Top 100 Everything” favorite Lizzy Caplan.

I have a hunch I watched Minutemen, but not a strong enough one that I’m 100% sure I did. I was in college when it came out, so if I saw the whole thing I’d probably recall it. (Also I probably wouldnt have watched a DCOM in college.) But I distinctly remember the guys hanging from the horns in the cheerleader outfit, so maybe I saw commercials or part of it.

Primer sounds great in theory, but I doubt I could make it through more than ten or fifteen minutes. I’ve been curious for awhile, so maybe I’ll have to watch and read one of those guides.

I enjoyed the perspective provided by your Time Machine and Looking Backward entries, too. “So good.”

I beloved as much as you’ll receive carried out right here. The caricature is attractive, your authored material stylish. nonetheless, you command get got an edginess over that you would like be delivering the following. sick indubitably come further previously again since precisely the same just about a lot steadily within case you defend this increase.