We here at EarnThis are no strangers to the power of books. Of all the media we consume, books rely most heavily on our creative faculties: Each reader is charged with conjuring the sights and sounds suggested by the written words. The book serves as our blueprint as we construct a story’s world in our minds. Without the constraint of a primetime hour or a 90-minute film script, books can tell sprawling tales, showcasing intricate worlds and thorough backstories (occasionally expanded still further in apocrypha and appendices, should intrepid readers feel especially curious).

We here at EarnThis are no strangers to the power of books. Of all the media we consume, books rely most heavily on our creative faculties: Each reader is charged with conjuring the sights and sounds suggested by the written words. The book serves as our blueprint as we construct a story’s world in our minds. Without the constraint of a primetime hour or a 90-minute film script, books can tell sprawling tales, showcasing intricate worlds and thorough backstories (occasionally expanded still further in apocrypha and appendices, should intrepid readers feel especially curious).

And then, sometimes, books can simply be fun.

If it seems ludicrous to tackle “books” and all the form entails in a single post…it is. So I’ve tried (emphasis: TRIED) to keep it concise by highlighting the ten line items covered here (some individual titles, some broader genres). These are not necessarily my “favorite” books, and in fact I have some choice invectives to lob at one selected text. Rather, all of these books have had a significant influence on me. Most I enjoy, many have changed me, all have made me think.

#1. Paranormal Books

Followers of my 100 Film Favorites Countdown already know I’m a sucker for cryptozoology and similar fields which peer into “the unknown.” Skeptics and scientists hold that logical reasoning and the scientific method are the only methods which can provide us with any “truth” about our world, and I don’t disagree. But there is much yet unknown about the universe. As Shakespeare wrote, in a quote often cited by “believers,” “There are more things in Heaven and Hell, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” Logic and science are our most useful tools for inquiry, but many “skeptics” dismiss certain questions outright… seemingly hypocritical for a group claiming to be “free-thinkers.” So while it’s generally a good idea to base assumptions and “beliefs” on evidence, I begrudge no man his search for truth, regardless of his route. The cryptozoologists and UFOlogists of the world are investigating places and ideas other, “harder” science practitioners may have overlooked. And even if nothing conclusive comes of their efforts, they produce some great, outlandish, and entertaining stories. And those stories make good reading.

I wish I could recommend a particular series or publisher, but there’s simply so much paranormal/cryptid/abduction/conspiracy literature out there that it’s hard to keep track. My interest in the genre was first piqued by a series of short picture books centered on various cryptids, such as Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster, as well as some more obscure creatures like West Virginia’s Mothman and the Jersey Devil. Later, I explored more “supernatural” topics. If I were to recommend a single book as an example of the genre, it would be a particularly comprehensive one which terrified me as a child (especially the section on spontaneous human combustion, complete with graphic pictures of charred limbs). Unfortunately, I’ve forgotten the name of the exact book, and there are only so many permutations of the words “Mysteries,” “Unexplained,” and “Unknown,” so there’s considerable title-overlap. If you’re looking to get into the genre (and it’s admittedly not for everyone), Time-Life’s Mysteries of the Unknown series is a fairly good starting-point.

Or, you know, you could just watch The X-Files. Expect more on that subject when my Top TV countdown rolls around.

#2: Trivia Books

These are the scores for my Pub Trivia league.

See “Team Teca,” up at the top there? That’s my team. I’ve only been part of the league for about a year, but my passion for trivia predates that involvement considerably.

My victorious team after a college tournament. If anyone’s curious, my top categories are Science, the History of Halloween, and Obscure Disney Movies (some categories pop up more frequently than others).

And here I am at the National Academic Quizbowl Tournament (NAQT) with a TJ team in 2006 – Ken Jennings was one of the readers.

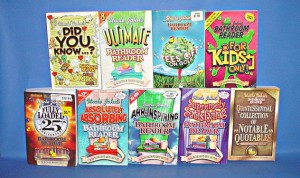

I may not be very pretty (as digging through old photos to find that last one made eminently clear), but I try to excel where I can…and leading people to victory as a font of factoids is something I’m pretty darn good at. Thus, I appreciate books which can expand my knowledge of a variety of subjects in brisk succession. Forget those Q-and-A format books. If I don’t already know the answer, I have to flip to the back of the book. And if I do know the answer already, then what do I need the book for? That’s why I stick with series such as “Uncle John’s” Bathroom Reader line. The “Bathroom Reader Institute” publishes a hefty volume every year, providing a near-constant source of quirky information on topics from famous disappearances to the history of the toilet. In my freshman year of college, the school band did home-stays with well-off families from an Atlanta school where we performed on tour. The room I stayed in, which belonged to the son of my host family, included a bookshelf stocked with the complete Bathroom Reader series…I didn’t actually sleep that night.

I read your books, kid. I read your books.

Of course, sometimes you have to take their claims with a grain of salt (and remember that they can’t predict the future – older books will have older “facts”).

#3: Mary Roach / Ben Mezrich

Some say fact is more entertaining than fiction, and these two authors raise strong arguments to support that. Mary Roach blazed onto the scene with her bestselling first book, Stiff, in 2003. Subtitled “The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers,” it details the many applications to which human bodies are put once they’re no longer…you know…breathing. From varying funeral / disposal practices (burial, cremation, disincorporation with lye, and even being compressed into stylish gemstones) to scientific studies (ballistics and vehicle crash tests), Roach humorously yet intelligently chronicles just about everything you can (legally) do with a corpse. She also addresses some things you might not be able to do, noting that, much to her dismay, no legitimate company exists which is willing to rearticulate you post-mortem into a science class skeleton. In a somewhat unrelated, but no less morbidly entertaining chapter, Roach briefly discusses animal experimentation, including an attempted head-swapping transplant between monkeys (which would’ve totally worked, except no one knows how to reconnect severed spinal tissue yet).

In following years, Roach has released a series of similar books which follow a set format: Single-syllable titles centered on a lesser-known area of contemporary scientific study. “Spook” covers scientific evaluation of supernatural claims. “Bonk” investigates sex research. “Gulp” explores studies of the digestive system. Unfortunately, she broke this trend with 2010’s “Packing for Mars,” about the future of manned space travel. Why not call it something like “Launch”? Oh well.

While Roach concerns herself with the kooky corners of science research, Ben Mezrich draws upon the grippingly dramatic, completely bonkers stories happening around us in everyday life. He also has a knack for picking cinematic subject matter: His novel “Bringing Down the House,” about a blackjack team of MIT students who mastered card-counting and embarked on an ill-fated spree to Vegas, was turned into the film “21.” And Mezrich’s “The Accidental Billionaires,” highlighting the scandal and interpersonal conflict behind the scenes of Facebook’s founding, inspired the Oscar-winning The Social Network. I eagerly await future films based on Mezrich’s books – one of his other titles, “Sex on the Moon,” tells the story of a low-level NASA employee who broke into a vault and absconded with a large collection of priceless moon-rocks…and then had sex with his girlfriend on top of the pile.

#4: A Christmas Carol

(Charles Dickens, 1843)

Sure, it’s been done to death. But that’s only because A Christmas Carol remains one of Dickens’ most accessible novels, as well as one of the most universally relatable fables in our cultural milieu. I have recently been reading TIme’s “The 100 Most Influential People Who Never Lived” (I order a lot of Time-Life books, okay?). As both an insightful study of some of literature’s most famous figures and a list of 100 things, the book is right up my alley. It offers a succinct explanation for the story’s appeal: The miserly Ebenezer Scrooge is offered a second chance “when he most needs and least deserves one.” At least in this story, it’s never too late for even the oldest and bitterest of us to seek redemption, turn our lives around and become “as good a man as any the good old city knew.” That’s a heart-warming notion if ever I heard one. The book did a few other noteworthy things as well:

1. It stands as one of the earliest examples of time travel in fiction (though this is somewhat dubious, as Scrooge can’t actually interact with the people in his “visions”). The chance to re-live our past or peer into, and perhaps alter, our future ranks among the most tantalizing prospects in all storytelling. By it’s very nature, time travel is compelling. And, as you’ll soon see, I “like” it.

2. Dickens admirably depicts Scrooge as more than one-dimensional. Though the trajectory of the story follows a “mean man” becoming a “nice man,” even at his most miserly Scrooge is shown to have depth, and his motives are hinted at. As the Ghost of Christmas Past shows us, Scrooge hates Christmastime because he associates it with sad memories (estrangement from his parents at a young age, a broken engagement, etc.). Even if we ourselves aren’t “grasping, covetous old sinners,” “sharp as a flint and solitary as an oyster”, each of us has had past screw-ups which shape who we become. We see some of our own faults in Scrooge’s hyperbolic character, and rejoice when he is offered a chance for salvation, as it suggests there may yet be hope for us, too.

3. This book saved Christmas. Seriously. The popularity of Dickens’ novel boosted significantly the western world’s enthusiasm for celebrating Christmas, which by the 19th century had somewhat fallen out of favor. But Dickens forever cemented the association of the Christmas season with merrymaking, gregariousness, and the celebration of hearth, home, and family.

Two final thoughts:

-I’ve always found it a little surprising that Scrooge is so shocked by the sight of his tombstone. Okay, yeah, I’m sure seeing your own grave would be a little weird, existentially speaking. But he’s an old man. Regardless of what he does and how he changes, he’s still going to die. And probably soon. C’mon man. You’re old. It really shouldn’t come as that much of a shock.

-What deal did Marley make, and with whom, to allow him to leave the spirit realm and recruit the three Christmas Ghosts, all in the name of redeeming Scrooge? I hear there’s a prequel novel out there which explores this subject. Just might be worth a read.

#5: The Phantom Tollbooth

(Norton Juster, 1961)

“I love The Phantom Tollbooth!”

“Of course you do. You’re a human being.”

-Cece and Schmidt, New Girl

For my money, The Phantom Tollbooth just might be the best “children’s book” ever written. It follows the journey of Milo, a boy who begins the story lacking direction and ambition. As Juster writes in the first chapter, “Wherever he was, he wished he were somewhere else. And when he got there, he wondered why he’d bothered.” But even the perpetually bored Milo is at least a little intrigued when the mysterious “phantom tollbooth” of the title inexplicably appears in his room. Having “nothing better to do,” Milo climbs into his toy car and putts off through the booth…and finds himself suddenly transported into the fantastic Kingdom of Wisdom.

The Kingdom is in chaos: King Azaz, the ruler of Dictionopolis, believes words to be the most important things in the world. His brother, the Mathemagician, rules the rival city of Digitopolis and holds numbers in a similarly high regard. As the two men fight for the superiority of their respective disciplines, they banish the land’s true rulers, Princesses Rhyme and Reason, to a prison “beyond the Mountains of Ignorance.” And as the skirmish consumes more and more of the Kings’ time and attention, seedy elements begin creeping into the kingdom…

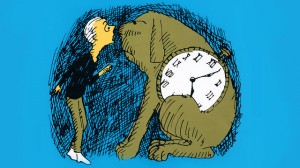

Aided by Tock, a “watch-dog” with a built-in clock intent on ensuring time is never wasted, Milo must trek beyond the Mountains of Ignorance to restore Rhyme and Reason to the land, if he ever hopes to return home.

If you couldn’t tell already, The Phantom Tollbooth is pretty metaphor-heavy. Milo’s adventure parallels humankind’s search for wisdom and truth, and virtually every character represents some aspect of that quest (or an obstacle hindering its completion). As you venture through the pages of Tollbooth, you encounter just about every “big idea” concept you could name…pretty heavy stuff for a kid’s book. While exploring Digitopolis, Milo asks the Mathemagician what the “biggest number” is. The ruler tells Milo to climb a staircase to “Infinity,” another city, where someone is waiting to answer Milo’s question. Of course, the staircase goes on and on, never quite reaching Infinity, and Milo gradually gets the point. In another chapter, Milo learns a little something (or a big something) about subjectivity and perception. He comes upon a tiny cottage, bearing different door placards on each of its four sides: “The Giant,” “The Dwarf,” “The Thin Man,” and “The Fat Man.” Milo knocks at each door, but is greeted every time by the same, very average-looking man. The man explains that to short people he appears tall, to fat people he appears thin, and vice versa.

Other characters embody concepts such as color, sound, and synonyms. Wordplay abounds as well – characters and landmarks are frequently named for and represent English idioms. Milo “jumps to Conclusions,” a distant, limbo-like island to which people who assume too much too quickly find themselves consigned. A brusque policeman who never allows his suspects a chance to speak their part is named Officer Shrift…and he’s very short.

The Phantom Tollbooth: Maybe it’s a bit pretentious, and it certainly pushes an agenda. But when that agenda says “Get off your lazy butt and improve the world by applying reason and replacing hatred with harmony”…well, it’s hard not to get on board. My one point of contention lies with some of the characters Juster poses as antagonists. For instance, midway through the novel Milo and Tock encounter Dr. Diskord, a scientist obsessed with noise. He collects and catalogues samples of all the world’s noises, along with his servant, “Dinn,” a genie-like creature whose name is a pun on both “djinn” and “din.” The Doctor and the Dinn are portrayed as relatively benign characters, but the idea that “noise” is inferior to “pleasant sounds” when it comes to seeking to understand the world seems problematic and highly subjective. To be fair, Juster depicts complete silence negatively as well.

Two other antagonists I find myself siding with just might reveal some of my own faults:

-The Humbug, another of Milo’s traveling companions, embodies pomposity and cowardice…but showmanship too. He’s funnier and a lot more fun than the uptight, ever-lecturing Tock. As an ardent P.T. Barnum admirer, I am firmly of the mind that the world always has room for a bit of humbug.

-Then there’s the Terrible Trivium, portrayed as one of the wiliest and most sinister “demons of Ignorance.” Trivium forces the travelers to perform “useless, but easy” tasks: Emptying a well with a thimble, moving a sand-heap with tweezers, and carving a tunnel through a mountain with a toothpick. Supposedly, Trivium (and by extension, trivia) stands as one of the worst enemies of wisdom because it inhibits progress, encouraging people to expend time and energy on “meaningless” pursuits. This, too, strikes me as highly subjective. Whose place is it to determine what’s truly “meaningful?”

But then, I guess I’m just trying to defend my love of trivia.

#6: McTeague

(Frank Norris, 1899)

“Below the fine fabric of all that was good in him ran the foul stream of hereditary evil, like a sewer. The vices and sins of his father and of his father’s father, to the third and fourth and five hundredth generation, tainted him. The evil of an entire race flowed in his veins. Why should it be? He did not desire it. Was he to blame?”

I first encountered McTeague in the form of a “reading comprehension” passage in a standardized test in tenth or eleventh grade. The passage comprised the first couple pages of Norris’ novel, introducing the title character. McTeague is a hulking but affable San Francisco dentist, dim-witted yet superhumanly strong (he frequently pulls patients’ teeth using only his thumb and forefinger as a parlor trick). And all he wants in life is a large gold sign in the shape of a tooth to hang outside his office.

Sounds like a pleasant enough fellow, right? Jump forward four years to an American Lit course in college, and imagine my surprise when I read past those first pages, only to discover that McTeague is a dark, depraved, absolutely brutal book which would give most R-rated filmmakers working today a run for their money in the gore department.

Things start to get squicky when McTeague meets Trina, his best friend Marcus’ cousin and fiance. Trina goes to the dentist to have a tooth pulled, and McTeague is entranced by her beauty. While she is under anesthesia in his dentist chair, the smitten McTeague commences a little one-sided makeout sesh. Later, McTeague confesses to Marcus his infatuation with Trina. Intending to be the noble, “better man,” Marcus breaks up with Trina to allow his earnest friend to court her. Soon, Trina and “Mac” are married.

Then Trina wins $5,000 in the lottery. It might not sound like much, but remember, this is 1899. And yet, the newfound fortune serves only to sour friendships and lay bare the characters’ baser instincts. Marcus now feels cheated out of the money and a wife, reasoning that if he had stayed engaged to Trina the money would be his. Incensed, he squeals on his former friend: McTeague has been practicing dentistry without a license, having learned the craft as an apprentice rather than through a formal school. McTeague loses his practice, and he and Trina are left destitute (she insists they must live off the meager interest generated by the $5,000 principle sitting in the bank). For the windfall has amplified Trina’s innate greed as well, and she gradually becomes a miser. She grows obsessed with money, and suddenly the bank seems too far away. She must have the money with her. Trina withdraws the grand total of the $5,000 in gold coins, with which she creates a veritable dragon’s hoard. And yet, she still refuses to give McTeague a cent to improve their impoverished situation. Perturbed, McTeague gives into his own instinctual vices, drink and violence.

Norris’ novel exemplifies the “naturalist” school of literature. Inspired by the work of Charles Darwin (who published On the Origin of Species in 1859), naturalists emphasized the animalistic nature of man: Under our veneer of civility, humankind, like any other species, is motivated by simple, “brute” desires, including hunger, lust, and, yes, greed. The concept of heredity also plays a prominent role in naturalist works. According to Norris, heredity provided a biological basis for the kind of predetermined, tragic outcomes common in classic Greek drama. Like “fate” or “the gods,” heredity determined many aspects of a person’s life, including his or her appearance, and perhaps character as well. An individual is powerless to change his “fated” genetic situation, his genes having been planted inside him before he was born. For all our pomp, there is no such thing as “the better man” – we are all rutting, scrabbling animals, driven by base urges and “programmed” by a set of hereditary instructions which “flow through our veins like a sewer,” bearing the impurities of all our ancestors since time immemorial.

Naturalists don’t mess around.

SPOILERS: Two scenes blew me away with the sheer cinematic power in their prose. First comes the scene in which McTeague, fed up with his wife’s now manic frugality, beats Trina to death in her own schoolhouse. A month later, her rotting corpse is discovered by her class of KINDERGARTENERS RETURNING FROM CHRISTMAS BREAK.

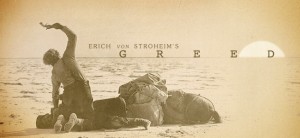

Finally, the book features one of the most memorable, visually striking endings in literature. Marcus tracks McTeague, now on the lam with the gold, to Death Valley. In their squabble, Marcus shoots McTeague’s mule, which falls and shatters his canteen, the pair’s only source of water. The doomed men then fight over the remaining store of gold. With a mighty blow, McTeague beats his one-time friend to death, but not before Marcus uses his last breath to handcuff himself to McTeague. The final tableau of the novel sees McTeague stranded in the middle of Death Valley, without water or transportation, handcuffed to a corpse.

(See reaction gif above).

Tidbit: Erich von Stroheim directed Greed, a film adaptation of the novel, in 1924. Stroheim was a perfectionist, and dedicated to recreating the book in its entirety. Consequently, the original cut of the film ran roughly EIGHT HOURS long. But during the protracted period of production, the film’s studio underwent a change in management (becoming MGM in the process). Stroheim was ousted and his film butchered. The theatrical cut of the movie ran just over two hours long, and the rest of Stroheim’s mammoth masterpiece constitutes one of history’s greatest “lost films.”

(Ernest Cline, 2011)

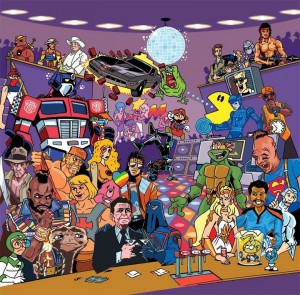

“A familiarity with Halliday’s various obsessions would be essential to finding the egg.

This led to a global obsession with 1980s pop culture.”

Referencing 80s pop culture is my bread and butter. 5 of my top 10 favorite films hail from the decade. So when I happened across a novel which promised 300+ pages of nothing but 80s references in a science-fiction framework, I had to have it. I have a habit of book-shopping in January (Christmas-and-Birthday-money season, plus it’s nice to start a new year with new books). So in early 2012, I passed up the latest Bathroom Reader installment in favor of Ready Player One.

The debut novel by Ernest Cline (the dude with the Ghostbusters Delorean up there), Ready Player One is a gamer’s version of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. In the not-so-distant future of the 2040s, teenage protagonist Wade Watts dwells in “the Stacks,” a midwestern city of ramshackle skyscrapers built from old mobile homes. Wade’s situation is par for the course on 2040s Earth – climate change and over-reliance on scarce fossil fuels has rendered much of the world desolate and impoverished. But never fear, the internet is here! In this brave new world, humanity escapes the grim real world by spending much of its time in “The OASIS,” a vast virtual reality created by technological pioneer James Halliday. Countless people live and work “in” The OASIS, on one of its many simulated worlds, and the droves of people “jacking in” to his realm seeking escapism, commerce, and some semblance of companionship have made Halliday the world’s wealthiest man.

When the reclusive Halliday dies, his estate releases a mysterious video will, in which Halliday poses a challenge to all OASIS players. He announces that he has hidden an “easter egg” somewhere in the game. The first person to puzzle through a long and cryptic trail of clues and claim the egg will become Halliday’s sole heir, inheriting a whopping 240 billion dollars and a controlling share in Halliday’s game company.

The world is enthralled by “the hunt” for Halliday’s egg, but no one quite knows where to begin. The initial clue consist of an “almanac” cobbled together from Halliday’s journal entries. It becomes clear that to find the treasure, one must be able to think like Halliday. And since Halliday was obsessed with the popular culture of the 1980s (and particularly arcade games, science-fiction, and Dungeons & Dragons), mankind quickly becomes a race of 80s aficionados (and nerds to boot). And Wade is determined to become the nerdiest, 80s-est of them all.

The hunt is on.

So there you have it. A treasure hunt story specifically designed for geeks. It was hard to imagine a book more tailor-made for me. And yet, as I read on, it became clear that the books was tailored to people even nerdier than me. By the halfway point, I found myself almost (perish the thought) getting sick of geek references. Our protagonist is – and this is a word I don’t throw around lightly (glass houses and all that) – a dork. Early in the story (mild spoilers), Wade becomes the first person to successfully locate the Copper Key, a stepping stone to finding the egg, and is transformed into a worldwide celebrity overnight. But it actually starts to get irritating to see him succeed, and the world’s admiration seems misplaced. Each of the various challenges features Wade and the handful of compatriots he assembles along the way nerdgasming over how well they have memorized things like Schoolhouse Rock songs and Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

But Cline redeems himself somewhat during a surprisingly dark period late in the novel. With the third and final key nowhere to be found, and the story’s antagonists (representatives of a rival tech company to Halliday’s who are trying to brute-force the quest) having caught up with the progress of Wade and his teammates, Wade takes a moment outside of the game to look critically at his life. He realizes that, in spite of all his celebrity, he is still just a sweaty virgin with no “real” friends, spending his days in a rubber interface suit plugged into a computer. This revelation is the most honest, brutal, emotional part of the novel, and it was difficult to care as much about The OASIS once Wade ultimately does decide to return, puzzle out the final clues, and “save the world” for his fellow nerds.

And yet, in the final treasure chamber, Wade meets a digital “ghost” of Halliday, who reveals that he spent his life lonely, awkward, and consumed by his obsessions. Halliday even offers Wade a means of erasing The OASIS, if he so chooses. Wade declines, but upon emerging in the real world, he expresses no desire to return to the game.

So, in conclusion…this book is really kind of a grab bag. If you’re a devotee of 80s culture, there’s plenty of fuel to get your geek on. But then there’s too much fuel, and you start hating geeks…and hating yourself for being one…and then you’ve finished the book. The biggest question I’m left with is where exactly Cline falls on the debate: Should one enjoy nerdy pursuits, or take a sledgehammer to their computer and go…mountain-climbing, or something? Cline himself certainly seems to revel in the geek life (take another look at his car). Ultimately I think the takeaway is that moderation is all things is a good goal to strive for. Whether a Delorean-driving man who can fill 300 pages with pop culture references is the best person to preach that message, I’m not sure.

This image was included in what appeared to be a Polish-language review of the novel. It’s actually pretty spot-on.

One last thought: In my opinion, Ready Player One provides the most realistic depiction of the future I’ve ever read. Particularly interesting are Cline’s predictions related to media (which closely match my own): By the 2040s, copyright, and by extension the movie studio / music label system, have ceased to exist due to rampant use of torrents and filesharing. In addition, harddrives have grown to the point that most people own complete collections of every movie and TV series, as well as just about every book, ever created. Even though the studios are gone, however, new media is more pervasive than ever, for the simple reason that every individual has become his or her own personal TV station. Through an online service that’s a combination of YouTube and live-streaming, nearly everyone is constantly producing, sharing, and remixing media. Perhaps this future seems so viable because we’re already halfway there.

#8: The Phantom of the Opera

(Gaston Leroux, 1909)

I know this post is getting long already, but this is the work I felt I most needed to discuss. My main point can be summarized as follows:

The Phantom of the Opera is a terrible role model.

And yet, I idolized him for many years (as I’m sure countless people continue to do). When I stepped back and took a more critical look at who he is and what he stands for, I found myself deeply shaken.

But let’s begin at the beginning. Gaston Leroux’s novel (and its many subsequent adaptations) tell the story of Erik, a man with a horribly disfigured face who spent his youth as a traveling circus freak, picking up a knack for magic and performance along the way. Erik’s greatest gift is his angelic singing voice, yet he can hardly perform in public outside of a sideshow tent due to his hideous countenance.

So the now-grown Erik shacks up in the catacombs beneath the expansive Paris Opera House, building a home for himself in the labyrinthine darkness. He learns the ins and outs of the Opera House better than any employee, and uses the knowledge to sneak around and extort the building’s owners to meet his various whims. His first request is simple enough: that the impresarios always keep a theater box available for use by the “Opera Ghost.”

Erik despises the Opera’s primadonna, Carlotta, whom he sees as talentless. Instead, the Phantom favors Christine Daae, a rookie singer who typically performs bit parts in the Opera’s productions. Erik begins visiting Christine’s dressing room, speaking to her from behind her mirror. He offers her music lessons and, luckily for him, Christine’s father filled her head as a child with tales of the “Angel of Music,” a muse-like spirit who may one day come to call bearing musical epiphany. Thanks to Erik’s lessons (and his strong-arming the Opera owners yet again), Christine excels as a singer and climbs to prominence within the Opera.

But Erik isn’t the only man captivated by Christine’s vocal prowess. One evening, Raoul de Chagny, a nobleman and childhood friend of Christine, visits the opera and is thrilled to see his former fling again. Before they can officially reunite, however, Erik spirits Christine away to his subterranean lair beneath the Opera, where he declares his love for her. Christine is frightened at first, but over the course of her captivity comes to care for for her mysterious abductor. That is, until she removes his mask and sees his horrible visage. The despairing Erik allows Christine to return to the surface, provided she promises to stay faithful to him.

As you might guess, that doesn’t last very long. Atop the opera house, Christine begs Raoul to take her far away, but of course the omnipresent Phantom overhears. Feeling betrayed, Erik hauls Christine back to his lair, where he declares she must marry him, or else he will blow up the opera house with a stash of gunpowder he has stored beneath the foundation. Erik further raises the stakes when he traps Raoul, Christine’s would-be rescuer, in a sadistic obstacle course/torture chamber. Christine kisses the Phantom, and the shock of experiencing human kindness and contact for the first time (Erik states he was never even kissed by his own mother) so overwhelms him that he lets both Christine and Raoul go free.

The final moments of the story vary depending on the adaptation: In the original novel, the Phantom dies some three weeks later of a broken heart, and Christine returns to bury him. In the 1925 Lon Chaney film, the search party which went after Christine and Raoul find and kill the Phantom, who does not put up a fight. In the 1986 musical, Erik disappears into the darkness, leaving the mob mystified.

My first exposure to the Phantom story came in the form of the Andrew Lloyd Weber musical, which I saw in first grade. Along with the Fiddler on the Roof soundtrack, I listened to the Phantom cast album almost every day when I was six. Before I go any further, let me point out that I’m far from the only person to be captivated by this musical: The show stands as the longest-running show ever on Broadway, and the only one yet to have surpassed 10,000 performances. It has raked in nearly $6 BILLION in box office receipts, and as such stands as the highest-grossing single piece of entertainment media. EVER. MADE.

Let’s take a look at what has made the musical, and the Phantom story in general, so phenomenally successful. Erik embodies two character types: the “tortured artist” and the shy, awkward guy hopelessly in love with a girl “out of his league.” Both archetypes are filled to brimming with pathos, and (particularly in the latter case) audiences can identify and empathize with the Phantom and his struggles.

But should we?

In the past year or so, I realized that Erik’s philosophy is the same as that of the “nice guy” much maligned on the internet of late. These “nice guys” perform kindnesses and favors for their lady loves, often acting at a distance, “from the shadows.” They tally up these “nice” deeds and reason that, even in spite of their own faults, if they perform enough favors and grand gestures for the object of their affections, she will eventually have no choice but to reciprocate in a romantic / sexual fashion.

But the world doesn’t work that way. The universe doesn’t operate on some grand karmic scale to mete out “fairness.” Even if it did, such behavior would hardly merit reward. The pathology of the “nice guy” is manipulative, self-centered, and disrespectful to women. And I fear that by identifying with the Phantom, I may have veered perilously close to some of these behaviors in the past.

So, “Phans,” take note. Erik is a rotten dude. On top of the manipulative mindset and practices of the “nice guy,” the Phantom performs more than a few outright atrocities. He blackmails, deceives, threatens terrorism and torture, and even murders people (in perhaps the novel’s most cinematic moment, the Opera-owners do call his bluff and cast Carlotta instead of Christine for an important performance, and Erik causes a great chandelier to fall into the audience, killing several patrons).

This dude is no hero. That’s not to say that his story isn’t worth telling. Erik’s emotions are real and raw and felt by many. But that doesn’t make them noble. As Christine tells him at the end of the Weber musical, it is not Erik’s face, but his soul which is truly twisted and ugly.

You don’t want to be this guy.

#9: Don Quixote

(Miguel de Cervantes, 1605 & 1615)

Speaking of nobility, we now come to another famous character I have connected with over the years, and now find that connection problematic.

Cervantes’ unforgettable tale follows Alonso Quixano, a Spanish gentleman who becomes so enraptured by works of chivalric literature that he “takes leave of his senses,” rechristens himself Don Quixote, and sets out to live the adventures of a legendary knight errant. He takes along as his “squire” the dim but level-headed Sancho Panza, promising Sancho an island of his own once their questing is complete.

Over the course of their adventures, Sancho is at turns bemused, mystified, and horrified by Don Quixote’s behavior. Quixote’s delusions of grandeur take the form of actual hallucinations, and he repeatedly perceives aspects of his mundane, “modern” life to be locales and characters from his books. In his mind, a barber’s bowl is a legendary helmet, and a common village girl (who may or may not have ever met him before) becomes the legendarily beautiful Dulcinea del Tiboso. In the most famous of his exploits, he “tilts at windmills,” imagining the structures to be a legion of fierce giants. He charges headlong at one of the “monsters,” and comes away from the experience with nothing but blade-cracked ribs.

Part 2 of the story, now typically included with part 1 in a single volume, but actually published ten years later, is more serious in tone than its predecessor. It continues Don Quixote and Sancho Panza’s adventures, but with a metafictional twist: The first Don Quixote novel exists within the world of the story, and its publication and subsequent acclaim have made the knight and his squire minor celebrities. But this just means that, on top of stumbling upon random “quests” as before, now there are people explicitly out to defraud the aging “madman” and his simple-minded sidekick.

In his final battle, Don Quixote is bested by a younger man from his hometown, posing as a knight. Quixote surrenders, and must abide by his conqueror’s conditions: namely, that he return home and abandon his “chivalrous” ways. He sadly trudges back to his house, and collapses into his bed with a profound sickness (possibly brought on by melancholy). Some time later, he awakens, now “sane” again. Despite Sancho’s protests, “Don Quixote” now insists on being called Alonso Quixano. In his will, the old man dictates that his niece is to be disinherited if she ever marries a man who reads books of chivalry.

Don Quixote endures in the public imagination for a variety of reasons. What drew me to the story as a boy (watching Wishbone) was the title character’s drive to stick to his guns and uphold his values, even when everyone around him dismisses those goals as spurious and derides him as a madman. As he sings in “The Impossible Dream,” my favorite song from the musical adaptation The Man of La Mancha, no matter what obstacles stand in his way, Don Quixote will always strive to “right the un-rightable wrong” and “reach the unreachable star.” I believe this persistence and nobility in the face of oppression is perhaps the primary reason that the character of Don Quixote remains so universally popular.

And yet, Cervantes’ novel is more complex and nuanced than many of the works it has inspired. As translator Edith Grossman observes, “You are never certain that you truly got it. Because as soon as you think you understand something, Cervantes introduces something that contradicts your premise.” Remember, Don Quixote renounces his obsessions and “delusions” at the end of the story. How are we to interpret this? What is Cervantes’ ultimate message about the proper place of chivalry?

I see a few possible interpretations:

1. The cynical. By the 1600s, the Romantic literature of the Renaissance and middle ages was already significantly dated. The genre’s romanticization of its time period rang false, and the values these works prized seemed out of place in Cervantes’ “modern” world, if indeed they ever had a place to begin with. The arc of the novel should be interpreted as a victory for realism and common sense over delusion and outdated notions.

2. The Impossible Dream. Don Quixote’s quest is bigger than one man. Just because Quixano eventually had the dream inside him snuffed out doesn’t mean it can’t live again in another who will carry on the adventure…perhaps Sancho, who undergoes something of a “Quixotification” over the course of the novel. Or perhaps it is up to the reader to keep the quest alive, to “fight the unbeatable foe” and “run where the brave dare not go.”

Or, maybe the answer lies somewhere between the two extremes. Maybe the world needs both Quixotes and Sanchos (but perhaps a few more of the latter). If we are to flourish, civilization requires both dreamers and hard workers. Both noble idealists and sensible realists. For better or worse, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza ride on.

Tidbits:

-This was totally the first instance of the “real superhero” genre. Kickass is basically just Don Quixote with more profanity (but the same amount of violence – Quixote repeatedly gets beaten within an inch of his life).

-In a 2002 list, a panel of international writers collaborated to determine the “100 Best Books of All Time.” The titles chosen were not ranked, as “they are all on equal footing”…all except for Don Quixote, which they dubbed the “best literary work ever written.” That’s quite an endorsement.

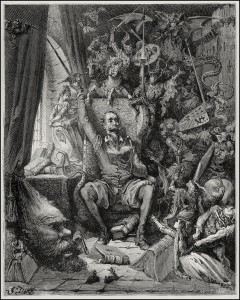

“Don Quixote in His Library,” an etching by famed illustrator Gustave Dore which currently hangs in my room.

#10: Folklore / Ghost story compilations

Let’s finish on a lighter note. Much of the earliest literature still extant revolves around mythology, and tells some of history’s most memorable and compelling tales. Folk tales reflect the time and place at which they were created, but also feature universally accessible themes. Compilations of such stories offer glimpses of different eras and cultures, and give us a sense of heritage. In a handful of pages they can make us laugh, cry, and thrill, and a few might just chill us to the bone. Here are a few collections which have stuck with me through the years.

My Book House

(Compiled by Olive Beaupre Miller, c. 1920-1932)

Published in a growing set throughout the 20s and as a full 12-volume series for the first time in 1932, My Book House is a compendium of primarily European and American poetry and folktales. What makes the series compelling is that it was designed to follow along with readers throughout their childhood – each of the twelve volumes is aimed at a slightly older age group. Volume 1, “In the Nursery,” consists mostly of nursery rhymes, meant to be read to children by their parents, while the final volumes are made up of often lengthy stories for adept young readers. I was first introduced to the Book House when my mother went on a nostalgic buying spree and tracked down a full set of the 1937 second edition (she had had a copy as a child herself). Though popular for decades, the series contains a few stories which were later recognized as racist (“Little Black Sambo” being the most notorious example). As such, the series was released in an updated, more PC version in the 70s, which proved to be its final publication.

Controversy aside, I admire the Book House publishers for their mission statement, first laid out in 1919:

- “First,–To be well equipped for life, to have ideas and the ability to express them, the child needs a broad background of familiarity with the best in literature.

- “Second,–His stories and rhymes must be selected with care that he may absorb no distorted view of life and its actual values, but may grow up to be mentally clear about values and emotionally impelled to seek what is truly desirable and worthwhile in human living.

- “Third,–The stories and rhymes selected must be graded to the child’s understanding at different periods of his growth, graded as to vocabulary, as to subject matter and as to complexity of structure and plot.”

Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark

(Alvin Schwartz and Stephen Gammell, 1981-1991)

First off, let me say that I’ve already written a more in-depth review of the series over at Brian Terrill Movie Night, during last October’s “Creepy Classic Countdown.” So I’ll try to keep things short and sweet here. In fact, I’ll just quote two paragraphs from that post that I feel sum up these life-altering volumes nicely:

“Almost every story is a masterwork of both concision and terror. Stories are rarely more than three pages long, but they manage to chill your bones and endure in your mind long after you’ve finished them.

“But the real source of the series’ power, and the element which, if you’re like me, evoked a visceral response in your memory upon seeing this post, is the mind-bendingly horrific illustrations by Stephen Gammell. With a few choice splotches of gray ink, Gammell managed to reach into the darkest recesses of the psyche and give fear itself a face. A terrible, terrible face. A rotten, eyeless face which burned itself into the impressionable brains of children everywhere.

“And we loved it, and came back for more.”

From Sea to Shining Sea: A Treasury of American Folklore and Folk Songs

(Amy L. Cohn and Molly Garrett Bang, 1993)

The final book I’ll mention here is the first I remember being excited about buying. I was 4 years old when the book was featured in an episode of Storytime, a Reading Rainbow-like series on PBS, and I begged my parents to buy a copy. From Sea to Shining Sea includes a variety of American folk literature, including songs such as “The Erie Canal,” which was performed on the show. But a sizable chunk of the book is dedicated to ghost stories, something Kino (Storytime‘s puppet host) failed to mention. The entry which had the greatest impact on me is probably the tale of La Llarona, a “wailing woman” from Mexican folklore said to be the specter of a woman who drowned her own children and later regretted the heinous deed. Legend has it she still wanders the riverbank, screaming, the blood quite literally on her hands, as she seeks out children to replace those she has lost.

I guess I read some creepy books as a 4-year old.

This post is massive and awesome.

Some thoughts:

-My first Bathroom Reader was “Absolutely Absorbing,” which Wikipedia tells me was the 12th in the series. Owning the complete series is something I had never previously realized I desperately want.

-I looked it up and $5,000 in 1899 is equal to about $140,000 today

-I really like your take on Ready Player One. My favorite thing about the story is just how — and I know this word is tossed around too often — EPIC it is. A huge evil corporation, massive quest, awesome final “battle,” very satisfying ending. I loved his escape from the prison. probably my favorite part of the book. To your list of complaints, I’d add that the dialog is pretty lackluster. Sounds like someone trying to hard to sound young and funny. (I ranked it #21 on the list of 47 fiction books I read in 2013.)

-I’m impressed you’ve actually read Don Quixote in its 400k word entirety. I’ve always thought of it as one of literature’s “white whales” — something that everyone wants to read, but which proves too long and dense for most to ever get through. (Moby Dick is kind of in that category, too.)

Okay, you got me. I got about halfway through Don Quixote, then skipped ahead to the end. I feel I knew enough of the main points through cultural osmosis.

(Also I had to give it back to the library by that point.)