Over in that house is a kid who thinks you’re the greatest, and it’s not because you’re a space ranger, pal. It’s because you’re a toy. You are his toy! – Woody

Rating: 4 stars (out of 4)

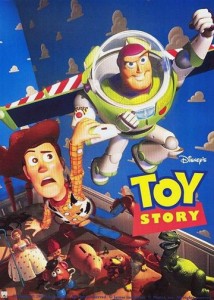

The success of Toy Story was almost unprecedented: Critics made it the fourth best-reviewed film of all time. Viewers flocked to the theater; no film sold more tickets in the US in 1995. Its maker, a little-known rendering company called Pixar, catapulted to stardom. Disney earned its biggest hit ever not made by the Walt Disney Animation Studio.

Oh, and it was the first computer-animated feature, ever. A few films — including Disney’s own The Lion King and Beauty and the Beast — previously mixed in some computer-generated imagery (CGI) as special effects. Plenty of commercials and theatrical shorts had been created entirely with electrons, but never a full-length film.

(And yet, the success of Toy Story was still only “almost unprecedented.” Exactly one film innovated so profoundly and successfully before it: 1937’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the first hand-drawn animated film ever.)

Pixar’s strange history as a computer hardware and software company — documented in the engaging The Pixar Touch by David A. Price — suggests that Toy Story could easily have come out as little more than a technical exercise. With all of the effort involved in creating a 80-minute computer graphic, little details like plot, characters, and script could have been lost in the mix.

That’s what makes the most staggering success of Toy Story — its pure, giddy, rich, poignant storytelling — one of the great, unlikely Hollywood victories of all time. Simply, Toy Story is nearly a masterpiece, one of the best films of its decade, and one of the best animated films ever.

It all starts with the premise, which is simple on the surface but cuts deep. Toys come to life when their owners are away. They have their own little world, organized like a small community. They worry mostly about typical things: love, wellbeing, friendship, safety. Their deepest desire is to be played with by their owners. This undercurrent of longing — to be played with and valued — allows the Toy Story series to embody all sorts of existential metaphor.

There’s also a powerful contradiction contained in the premise: the toys can’t (or don’t — more on this later) move or express anything when humans are around, even though entertaining humans is their life calling. This paradox drives much of the film’s suspense and thematic depth.

Among the key triumphs for the film is its multi-dimensional characters. Most memorable are the odd couple at the heart of the film: Woody and Buzz Lightyear. Woody starts the film Andy’s favorite toy, a position that commands respect among his fellow toys. Fortunately, he’s a good leader and he organizes the toys into a productive community. As two stressful events — moving day and the dreaded birthday, when old toys are replaced with new gizmos — approach, Woody does his best to keep Andy’s toys calm and prepared for any disaster.

With Woody’s power and responsibility has come an inflated self-importance. He relishes in the role as favorite toy and leader. Admittedly, it’s an important role: Without him, it seems, there would be no order within the toys’ community and no hero for Andy’s elaborate, imagined adventures. The other members of the toy community mock Woody’s seriousness a bit, but seem to respect his authority.

Woody is voiced brilliantly by Tom Hanks, who infuses the protagonist with humanity and comedy. His inflection and energy turn some plain lines into classics, especially one of cinema’s great rants: “You are a toy! You aren’t the real Buzz Lightyear! You’re an action figure. Y0u are a child’s plaything!”

Equally memorable is Buzz Lightyear. Woody had spent the morning before the birthday party comforting his fellow toys that they wouldn’t be replaced, but Woody himself turns out to be the one in danger. Buzz Lightyear knocks Woody off the bed and off the top of the toy totem pole. All of the toys immediately embrace him as the new, cool toy and leader. Even Woody’s beloved Bo Peep admits that Buzz has “more gadgets on him than a Swiss Army knife.”

Yet Buzz has a self-delusion that surpasses Woody’s, and it’s this confusion that drives the film: He doesn’t realize that he’s a toy. He thinks he’s really a space captain. As Rober Ebert put it, “Buzz is the most endearing toy in the movie, because he’s not in on the joke.”

Throughout the first half of the movie, Buzz operates as if he’s temporarily crashed on an alien world and has to repair his cardboard box space ship. This leads to some of the funniest moments in the film, when Buzz makes off-handed observations in a militaristic, formal tone. “I don’t believe that man’s ever been to medical school,” he remarks when toy-abuser Sid plays the part of a toy surgeon.

Because of Buzz’s persistence to his world view, his transformation is quite poignant. His belief that he’s the Buzz Lightyear comes crashing down, quite literally. Woody is forced to make a change in his self-outlook by the end of the film, but it’s nothing compared to the complete identity crisis Buzz goes through.

Credit voice actor Tim Allen for capturing these complexities. Billy Crystal was initially desired for the role, but he turned down the role, so Allen was offered the gig. Crystal’s rejection was ultimately a fortuitous twist to the film. Allen’s everyman, blue collar take on Buzz allows the character to remain relatable. Crystal’s detached, high-pitched voice (later utilized to great effect in Monsters Inc.) could have pushed Buzz into an unlikeable character.

As brilliantly-conceived as Buzz and Woody are on their own, the real magic happens when the two are together, which is the better part of the movie. Both are completely confident of their place in the world, and so the first half of the movie is loaded with great scenes where each thinks the other is the craziest toy alive.

This comes to a head in the aforementioned scene at the gas station. Buzz tries to escape to get in touch with Star Command to defeat the Emperor Zerg, while Woody just wants to get back home in time for moving day. “You are a sad, strange little man, and you have my pity,” says Buzz. It’s a remark that seems woefully ironic at first, but grows more true the more you think about it: Woody had forgotten that his role as a toy was the be there for Andy, not fulfill his own self-image as a leader and hero.

After Buzz’s delusion collapses along with his self-meaning, Woody helps him infuse a new meaning. In one of the more brilliant scenes of the film, Woody and Buzz’s flawed world views intersect: Woody, to escape his plastic cage, has to admit that he’s not inherently “better” than Buzz or any other toy, even if he fancies himself important. Buzz, with the help of a Woody pep talk, sees that their is a certain value and duty in being a toy. His radio may be a sticker, but the “Andy” scrawled on his foot is truly a badge of honor and responsibility.

This turning point kicks the film into its third act, which finally sees Buzz and Woody working together in a radical shift from the first two acts. Fortunately, the two cooperating is nearly as entertaining the two clashing, particularly in the climax. My favorite moment of the movie is when the two re-use an earlier exchange in an entirely different light: “This isn’t flying, this falling… with style.”

While many of the aforementioned scenes rank among the movie’s many superior moments, I also want to commend the opening of the film. So much of what makes Toy Story great — the respect of imagination, the honoring of the sacred bond between child and toy, the thrilling use of CGI to create perspectives and worlds that move — are summarized in those first five minutes. Plus, there’s the music, the brilliant combination of score and original songs by Randy Newman, epitomized by “You’ve Got a Friend in Me.”

“You’ve Got a Friend in Me” has since become a standard. The simple, catchy tune works a basic expression of love as well as an embodiment of the core themes of the Toy Story series. Particularly seeing the later films’ use of the song, it’s hard not to marvel at how well the song captures so much at the heart of Pixar’s films.

Newman also contributes two other original songs to Toy Story, “Strange Things” and “I Will Go Sailing No More,” the former of which works better than the latter. Though I love the scene where Buzz learns the truth about his toyhood, the song adds an extra layer that was not necessary. The scene would have probably been more effective with a simple score.

Aside from that, the music in Toy Story is exceptional. Newman’s score resonated so strongly that he has been brought on for five more Pixar scores. Toy Story 3 holds his best work, but Toy Story is no slouch, particularly during the climax.

Toy Story shines in the details as much as it does the sturdy framework of the story. The side characters — from the loyal Slinky Dog to Spud the maniacal hound to Hamm the gearhead — are all given distinct personalities and animated with an astonishing amount of humanity and personality. Rex the cowardly dinosaur sticks out as particularly funny, but it’s hard to crown anyone other than the little green aliens as the most memorable secondary characters of the film. I guess all space toys have trouble with their grips on reality (including Zerg from Toy Story 2).

There are so many inspired small touches of artistry — reflections on the glass of Buzz’s helmet, messages on the Spell ‘n’ Speak, throwaway one-liners, quick and creative establishing shots that would have been impossible in hand-drawn animation — that I’m willing to forgive the movie’s few flaws that come out after close watching, particularly on the technical side. It’s really incredible how little of the film suffers from technical issues (credit the brilliant direction of Lasseter and others for hiding most flaws) but it makes the few poorly-rendered animations of humans and dogs all the more glaring.

I also found the storyline of Sid’s toys a little bit less engaging than the rest of the story. While I enjoy the idea of a toy hell at Sid’s house, the interaction with his deformed toy experiments is nearly too on-the-nose for the rest of the story which maintained a subtle and understated thematic backbone. The “don’t judge a toy before you really know him” message is a bit excessive even if it plays nicely into the growth of Woody.

The semantics of the toy/human relationship are also a bit fudged here. This film seems to indicate that toys choose not to speak and interact with humans. After all, Woody does come alive (*) in front of a person for a brief second in Sid’s final scene. This seems at odds, though, with other basic properties of the human-toy world division as shown. The notion that toys can’t be seen “alive” by humans for metaphysical reasons, not by choice, seems to be the ultimate explanation in the other chapters of the trilogy and is one that seems to fit the logic of the world a bit better.

(*) Before he comes alive in front of Sid, Woody mentions that they’re going to have to “break a few rules.”

My last complaint is the closing scene of the film. I’ve never been a fan of movies that end on a punchline, and so the joke final line and shot end the affair on a down note compared to a film that’s otherwise so universally strong. It’s a flimsy complaint, but these are the types of nits you pick when a film is so close to perfect.

These complaints aren’t enough to tarnish in any meaningful way the giddy excellence of Toy Story. Sixteen years later, the original still packs a tremendous punch and tells a story worth experiencing again and again. It may not tackle big ideas as ambitiously as later Pixar films, including the later parts of the Toy Story series. But, scene-by-scene, it’s perhaps the strongest film the studio has produced. There’s not a minute in these 81 that fail to soar to infinity and beyond.

A few other thoughts:

- One underrated element of Toy Story is the variety of faces that Woody makes. Had his faces failed to be effectively expressive, the film would have greatly suffered.

- There’s a bit too much emphasis on Mr. Potato Head here: too many gags that involve his face falling apart and perhaps too much of his bitter skepticism.

- Toy Story has a few silly, throwaway gags from characters or beats we never see again: The shark who steals Woody’s hat, Buzz’s experience as Mrs. Nesbitt, and a few others.

Pingback: Toy Story (1995): Co-Review | taestful reviews