It’s basically impossible to succinctly describe Bruce Springsteen artistic output. He is large, he contains multitudes.

The Boss has released 18 studio albums over the past 45 years and developed a reputation for unsurpassed, marathon live performances. His commitment to heartland rock is easy to parody; it’s also key to his expansive creative achievement. Springsteen took a cliche mindset towards rock — of capturing the sound and feel of lower-middle class America with earnest intensity — and exploded it into a sprawling canvas for dramatic, poetic masterpieces.

Any discussion of Springsteen’s long career is compelled to break it into segments. I am going to break it into two periods: the era before he first broke up the E-Street band and moved to LA (1973-89) and the era after (1989-present).

Every album in the first era is essential; nearly every album in the second is non-essential. The rest of this article will focus mainly on the eight albums Bruce recorded from the former, and will entirely dismiss the latter. Trust me; it’s simpler this way.

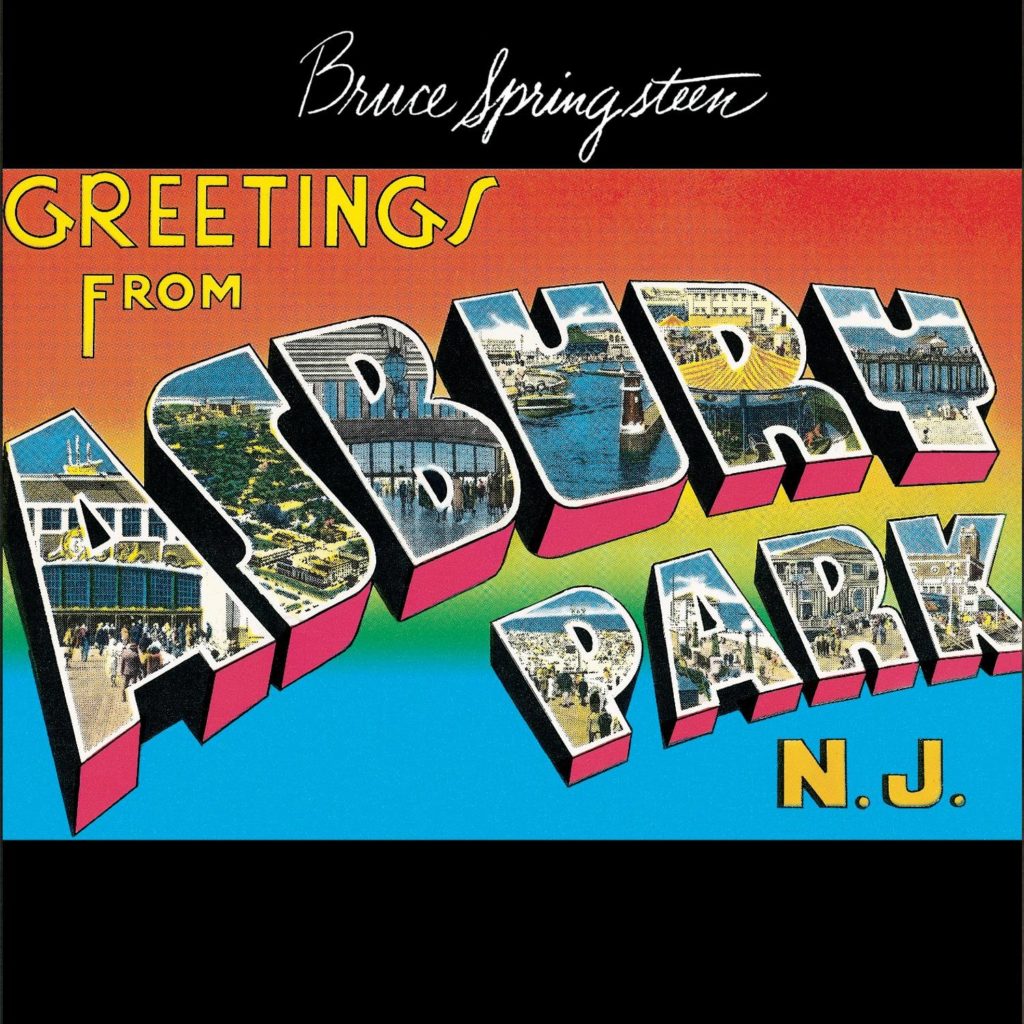

Bruce Frederick Joseph Springsteen was born in 1949 and released his debut album at age 24. Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. offered the vision of an earthier Bob Dylan, ruminating on young love and political purity with polysyllabic ease. Moments of the album are fully formed — notably the heart-rending “For You” about a wounded, distant lover — while others display a raw writing talent still in need of some life experience.

Greetings remains a compelling listen. Bruce’s intense gaze on characters and conundrums is already developed, but the devil is in the details. Some of the songs are too fast and slick (“For You”); others are too slow and sketch-like (“Mary Queen of Arkansas”). All of them are a bit sonically shallow. The lyrics are simply stunning in their literary gusto and enthusiasm for American life; they provide a stark contrast to the cynicism that Bruce would develop over the next several years.

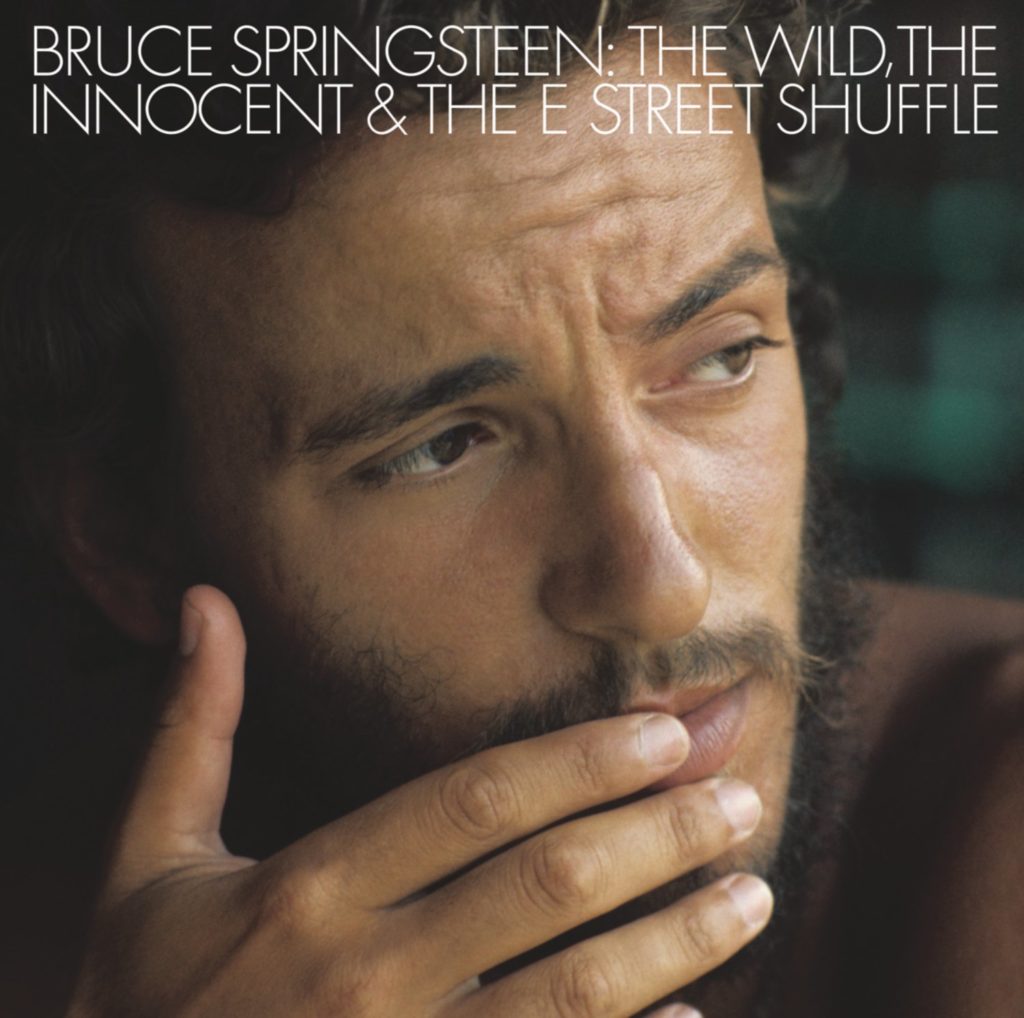

As promising as Greetings is, it was hardly appropriate preparation for The Wild, the Innocent, and the E-Street Shuffle, Springsteen’s sophomore triumph. He released it in 1973, less than a year after his debut, but it is an artistic leap.

In fact, Bruce Springsteen’s second album is quite possibly my favorite by any artist, ever. Period. A nostalgic farewell and euphoric celebration, E-Street Shuffle is buoyed by the E-Street Band’s jazzy contemplation of urban chaos, and the beauty that emerges from within.

I can’t bare the thought of my readers not enjoying this odyssey, so please: go listen. All seven songs are perfect, and required listening. From the jittery opening “E-Street Shuffle” — which captures the seductive rhythm of a big city — through a half dozen romances and heartbreaks, through closer “New York City Serenade” — which transforms an awkward hookup into an exploration of the unexpected artistry of burough life — Bruce leverages The E-Street Band’s profound expressiveness into luxurious poetry.

I have to give a shoutout in particular to “Rosalita,” a pulsing love letter to a young Latina woman. It’s a breathless proclamation, somehow both nuanced in irony and warp-speed in desire, as rock and roll should be. “Rosalita” has become a high-energy live staple, but the life- and flesh-loving studio recording might be the greatest rock record of the 20th century. “I just wanna be in love, ain’t no lie,” indeed.

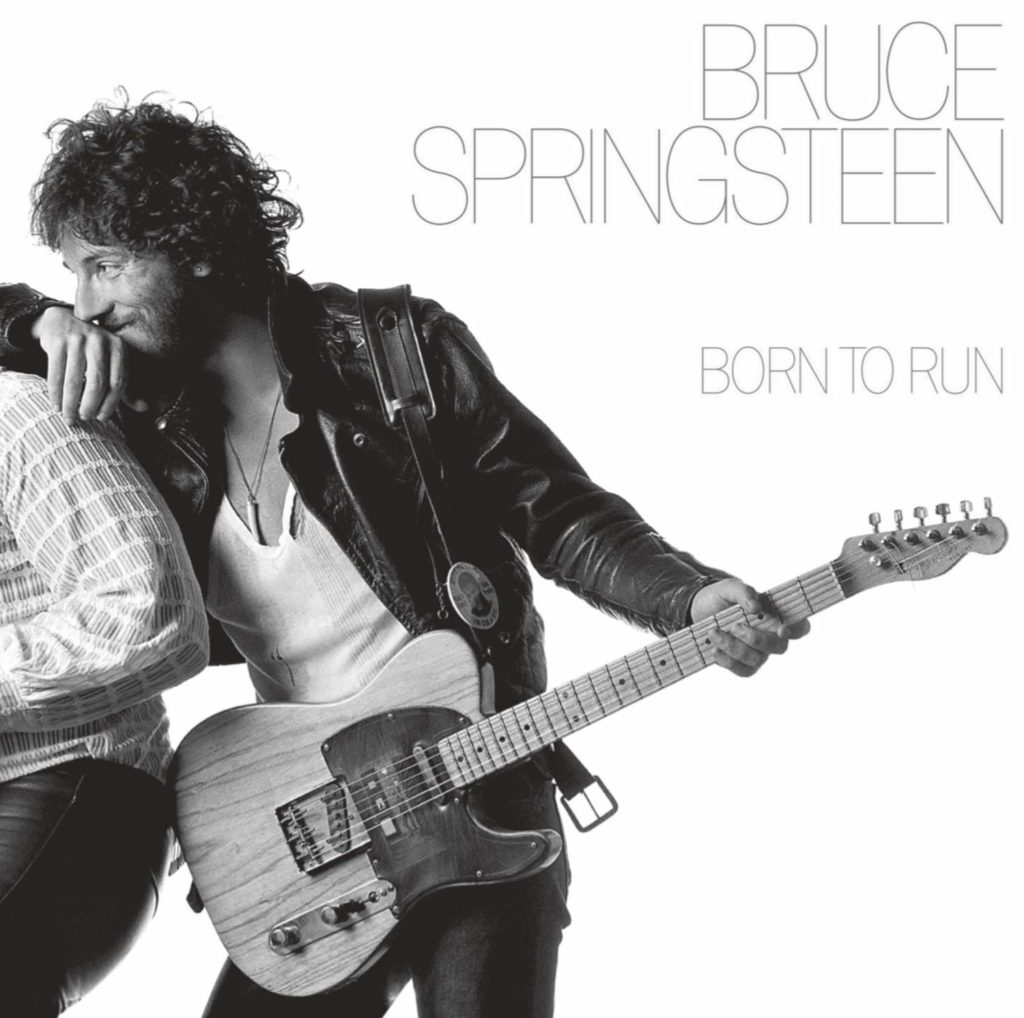

While E-Street Shuffle’s full-hearted pilgrimage resonated with critics, it failed to gain much commercial traction. The masses wanted theatrics and melodrama. They wanted for love to transcend life’s bad breaks. They wanted a “last chance power drive.” They wanted Born to Run.

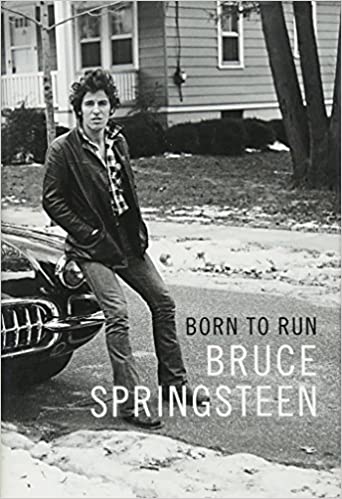

Bruce’s third album came out in 1975, two years after E-Street Shuffle, and it’s one of rock’s towering achievements on every axis. It earned Bruce magazine covers and went triple-platinum. Where his first two albums relied on performance ahead of production, Born to Run brings a Spector-like dedication to layered soundscape. The result, paired with Bruce’s operatic lyrics of street struggles, is a monument of rock ‘n’ roll force.

The huge sound couples nicely with equally giant songs. The title track is rightfully iconic, conveying such drama that its climax of “broken heroes” takes my breath away every time. “Backstreets” is another winner, a gripping portrait of two friends who never found their break. And the closer, the ten-minute “Jungleland,” is half West Side Story, half Wagner — a “real death waltz between what’s flesh and what’s fantasy.”

My personal favorite track — a contender for my favorite song ever — is the opener, “Thunder Road.” Bruce lays out his vision in clear terms: Gone are previous albums’ “Cheshire smiles” and “aurora rising behind us.” Bruce is ready — desperate — to break the bonds of decaying normalcy. His vision is grand and sad, but tinged with hopes of “pulling out of here to win.” That sax outro is Heaven.

With Born to Run, Bruce traded in the exuberant lilt of his first two albums for a dramatic intensity that pays dividends. But this newer, more disillusioned, rocker hits a few minor road bumps. A couple tracks, like “Night” and “She’s the One,” lack the specificity and music-lyric synergy of Bruce’s best works: The words are simply a bit boring for The Boss.

Nonetheless, nobody can question Born to Run’s status as a masterpiece and a seminal point in the history of American rock.

As the global acclaim poured in, the E Street Band’s internal troubles picked up. Bruce decided to ditch his first producer-manager, Mike Appel, in favor of Jon Landau. The ensuing legal struggle kept Springsteen from recording for more than a year.

During that time, Bruce kept writing and performing. He wrote and discarded whole albums, performing snippets in live shows along the way. One abandoned album, The Promise, became a bit of rock and roll myth along the lines of The Beach Boys’ SMiLE. (And, like SMiLE, The Promise finally received a proper release to critical acclaim decades later.)

The album that finally came out in 1978, three years after Born to Run, was titled Darkness on the Edge of Town. It discarded operatic angst for something leaner and meaner. Darkness never achieved the widespread love of Born to Run, but it has gone down as a true classic. It’s certainly one of my two or three favorites in his discography.

The conventional wisdom is that Bruce embraced the mindset of his manager, Landau, who doubled as a revered rock critic. As any busy critic would appreciate, Darkness is less sprawling and more direct. It grows angrier as it digs deeper into the American heartland. The production is tense, often muscular, and every song is unmissable.

Opening with a trifecta of “Badlands,” “Adam Raised a Cain,” and “Something in the Night,” Bruce contemplates inevitable failure (with whiffs of fleeting glory). It’s a stunning stretch of three songs, as Bruce considers the sins we inherit from our community, our parents, and our human nature, respectively.

The album’s most moving moment is “Racing in the Street,” a stark piano ballad. Bruce inverts Martha Reeve’s boundless optimism into a devastating study of a trapped couple in need of absolution. It’s an understated counter to Born to Run’s themes of driving to freedom, of escape requiring nothing more than a working carburetor and gas pedal. It’s a true stunner.

It took Bruce three years to release Darkness’s ten perfect tracks. But it took him less than two to release his next album: a messy, brilliant double album. The River, released late 1980, is yet another artistic flip-flop, and yet another huge victory. Springsteen eschews dour focus for a broader, more diverse effort. Like the titular body of water, this album sometimes runs light and clear, sometimes dark and silty.

On the one hand you have the album’s first disc, featuring drinkalong “Sherry Darling” and infatuated “Crush On You” and romantic “I Wanna Marry You.” Bruce has never been more unburdened than here, goofing on rockabilly and rural partying. He even sounds like he might be having unironic fun — unprecedented for The Boss.

The second half flips the perspective. Bruce is bitter and devastated at his community’s failing. Starting with the bleak “Point Blank” through the heartbreaking “Wreck on the Highway” — a grappling with spontaneous tragedy — he sets a second path for his talent, one that Bruce would take to its extremes on his next album.

The River had brought more color and variety to Springsteen’s sound. Nebraska flipped The Boss narrative on its head with an aesthetically and thematically stark album unlike anything he’d released.

Following a massive, exhausting tour, Bruce hung out at home, reading and watching old movies and writing dozens of songs. He recorded demos on a cassette machine using just his voice and an acoustic guitar. Inspired by old blues and hillbilly records, he mixed the demos with the reverb and echoes turned way up.

Springsteen recorded the songs in the studio with the E-Street Band, but it didn’t sound right. Then, he recorded them in the studio solo, and it still didn’t sound quite right. So he finally decided he’d just release the cassette demos themselves, in all of their lo-fi glory (or lack thereof).

The result is a stylistic marvel: Spare and haunting and echoing, these tracks are defined by their sonic brooding. But within the stripped down timbre, Bruce explores a whole spectrum of storytelling modes: “State Trooper” is tense as a thriller, while “My Father’s House” is mythic and nostalgic. Many of the songs sound same-ish thanks to simple, folk-like melodies, but that only expands the impact of the album’s minute contours.

Bruce brought his storytelling to new heights, too as he surveyed crime and poverty and the impact they have on families. “Atlantic City,” the album’s lone single, cryptically alludes to the narrator’s illicit act without ever specifying it, though his repeated chorus of “everything dies” implies violence. “Nebraska,” the title track, is another highlight, setting the tone for the album, as Bruce inhabits the mind of a romantic murderer.

But few Springsteen tracks have given me quite so much to think about as “Reason to Believe,” the closer. It warps the album’s ruminative quality into a black absurdity. I really just have to share the lyrics of the first verse with you:

“Seen a man standin’ over a dead dog lyin’ by the highway in a ditch / He’s lookin’ down kinda puzzled, pokin’ that dog with a stick / Got his car door flung open; he’s standin’ out on Highway 31 / Like if he stood there long enough that dog’d get up and run / It struck me kinda funny; seem’d kinda funny, sir, to me / Still, at the end of every hard day, people find some reason to believe”

“Reason to Believe” – Nebraska – 1982

Every time I listen to the song my opinion of the dude poking the dog changes. Why does he expect the dog to wake up? Why does he care if it does? Is there any reason to hope for something that will never come true? Or, as Bruce pondered in “The River,” is “a dream a lie if it don’t come true, or is it something worse?”

Mercifully, he’d take a 180 on the outlook and tone of middle class life with his next album, one of the all-time smashes in American rock ‘n’ roll.

Born in the USA’s cover features a denim-clad ass, which is both a perfect image — vintage mid-1980’s indulgent fun — and a bit deceptive, because Born in the USA isn’t macho posturing. It’s pretty and fun, but it also digs deep.

Take the title track, which sounds like a patriotic mantra; then you listen to the words and realize it’s about a busted American dream: “End up like a dog that’s been beat too much / ‘Til you spend half your life just covering up.”

This is one of Bruce’s most consistent albums, and its smashing commercial success is proof: seven of its twelve tracks made the Billboard Top Ten. Tonally, the album embraces human connection and strength: the magnificent “No Surrender” is his biggest battle cry since “Born to Run,” while closer “My Hometown” finds dignity and progress in multi-generation one-horse towns.

“Dancing in the Dark” is the album’s most enduring moment, one of the defining tracks of Gen X young adulthood (even though Bruce is a Boomer): he stammers his inadequacies, laments a dream and a love just out of reach, yet vows to keep searching for a “spark” to ignite his life. It’s been played 160 million times on Spotify.

Yet, for me, the defining Born in the U.S.A. track is “Glory Days,” the perfect straddle of the album’s two tones. It’s a disillusioned portrait of an alcoholic who peaked in high school — and simultaneously an honest-to-goodness bar band stomper. Bruce mocks the aimlessness of its characters, but doesn’t disdain them. It’s a delicate, perfect, balancing act.

Despite universal acclaim and record-breaking sales, Born in the U.S.A. typically falls behind his earlier albums in fan adoration. In a massive poll of obsessives ranking his best songs, only two Born in the U.S.A. songs landed in the top 50. It almost tempts me to call this platinum-selling, five-star landmark an underrated album.

Bruce’s discography is a perpetual pendulum, so it should come as no surprise that he followed his cathedral-sized slice of Americana with something more personal and pained.

Tunnel of Love, Springsteen’s eighth album, consists mostly of midtempo, diaristic love songs produced with heavy doses of synths and drum machines. If this sounds familiar, it’s because this describes basically every rock album of the late 1980’s. Still, it was new ground, sonically and lyrically, for The Boss.

This is the type of album critics call “mature” — complex, well-written vignettes without simple resolution. The tension here is more mundane, less operatic than ever: glances and sighs and touches. Much of the lyrical content addresses, directly or indirectly, Bruce’s imploding marriage with Julianne Phillips. Perhaps the most indicting song is the album’s signature track, “Brilliant Disguise,” about two lovers who have to pretend to be other people around each other.

Most of the album is drowned in synthesizers, Bruce’s new composing toy. The overall feel of the album is a bit droning, which aligns with the album’s each-day’s-a-chore lyrical tone.

A few tracks spike the formula. “Spare Parts” is some straight-ahead blues, and my personal favorite number on Tunnel of Love (Janey is a heroine). Meanwhile, “Cautious Man” features a stripped-down production that evokes Nebraska.

During the album’s recording and tour, Bruce ended his three-year marriage and began a relationship with his backup singer, Patti Scialfa. He also informed the E-Street Band that he would no longer need their services: He was moving to California.

And that’s where my focused attention on Springsteen discography ends. The breakup of the E-Street Band (though they’d reunite a decade later) provides a clean end of The Boss’s peak artistic output. Nonetheless, here’s a quick summary of the rest of his discography:

After a five year break, Springsteen simultaneously released two albums, Human Touch and Lucky Town, both recorded in Los Angeles with session musicians. Both were critical flops. In 1995 he penned the all-acoustic The Ghost of Tom Joad, which got decent reviews but bombed in sales (an awful album cover probably didn’t help).

The late ‘90s saw some re-releases (including a smash Greatest Hits album) and archive digging (the four-disc Tracks compilation), plus plenty of touring in the wake of the E-Street Band’s reunion.

Following the September 11 attacks, Bruce released The Rising, an acclaimed call for resilience and redemption. It reshaped the narrative around his career: A legitimate hit with zeitgeist power, The Rising ushered Bruce from awkward middle age to rock statesman, effectively immune from criticism, a position he’s held in the 17 years since.

Since ‘02, he’s released six original studio albums: Devils & Dust, Magic, Working on a Dream, Wrecking Ball, High Hopes, and Western Stars. All except the latter topped the Billboard album chart and received rave reviews from Rolling Stone, aka the Boss-is-God Rag. I personally haven’t listened to any of them more than one time through, so I’ll leave my implicit review of these albums at that.

(I should note that my cynicism of these albums is not universal; many dedicated Springsteen fans rank some tracks from later albums among his best ever.)

The years 2016-2018 were big ones for Bruce. First, he released an acclaimed and bestselling autobiography entitled Born to Run. I have a copy on my shelf which I hope to read soon.

In 2017, Bruce was given a yearlong residency at Walter Kerr Theatre on Broadway, doing acoustic shows with storytelling in between tracks. He eventually recorded the show, and released both as a Netflix special and live album.

It’s my favorite thing he’s released in years — intimate, funny, seasoned, just masterful. I highly recommend it. It’s actually not a bad entry point to Bruce’s personal songwriting voice.

The most curious late-Bruce album is not an original, but We Will Overcome: The Seeger Sessions, a Pete Seeger cover album. It charts a new potential path for Bruce as a folk archaeologist, elevating American standards with his natural charm. It’s a loose, conversational album, which is exactly what I love about it. (Frankly, I’m more interested in America’s great, overlooked songs than anything a 70-year-old millionaire has to say.)

I’d love to spend a few more thousand words here dissecting some of Springsteen’s songwriting and motifs. Some of his favorite symbol are: water (as a source of destruction and absolution), day vs. night (as a line between societal conformity and rebellion), and houses (as an emblem of social standing).

But I’ll wrap this up by pointing out his most recurrent and important symbol: Cars.

In Springsteen’s lyrics, cars capture so much about the a human’s agency, or lack thereof. In “Thunder Road,” they’re an escape from hometown “ghosts”; in “Racing in the Street,” they’re the false hope and empty thrill of whipping around dead streets with nowhere to go; in “State Trooper,” they’re the careening force of destruction as impulses go unchecked.

When Bruce starts talking about a car, that means it’s time to start paying attention. Because he’s doing what he’s done time and again throughout his career:

Take what could have been so mundane and prosaic, a blue collar kid singing with a local band about ordinary people, and escalated it to greatness. “Pullin’ out of here to win,” indeed.

It was really neat when he and Max Wineberg played together