Seven books. Seven horcruxes. Seven Defense Against the Dark Arts teachers. It’s an important and recurring theme in the series. I was tempted to rank the series #7 on my Top 100 Everything for that reason alone. (Plus, you know I love the number seven.)

In that spirit, here is my Harry Potter story in seven parts, and something I found to love about the series every step along the way.

⚡⚡⚡

When I was eleven years old, I loved stories — video games, TV shows, action figure battles in our basement — but I wasn’t much of a casual reader. I’d read a few Avi books a year, and whatever was assigned for school, but that was it.

My mom had read a newspaper article about how popular a kid’s fantasy book series was becoming, and she got me the first book, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, from the library. It was a little bit longer than most books I usually read, but I gave it a try.

I was swept away from the start. Of course I was. What misfit preteen wouldn’t be? The author, JK Rowling, placed us in the head of an ordinary boy. Like me, he finds plenty of his early adolescence world to be alienating. Sure, Harry had it worse than I did: His guardians were abusive and he slept in a dusty cupboard. But, like me, he’s doomed to be ordinary and miserable.

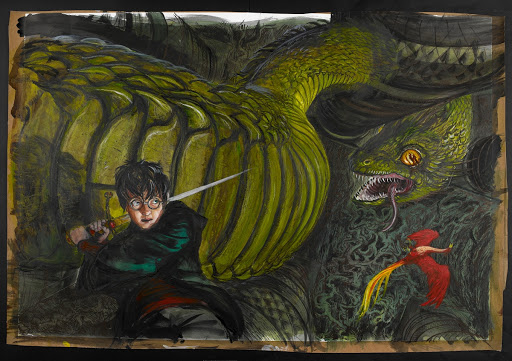

Except he isn’t! He has magic powers. There’s a whole world where he doesn’t just fit in, he’s beloved and revered. He’s SPECIAL just by being himself. The things he does are important: Resisting cruel bullies and fighting monsters and solving real mysteries. He gets to ride broomsticks and rescue dragons and fend off The Dark Lord and be a hero.

Harry’s saga would eventually span over 4000 pages, hundreds of characters, sprawling ethical and political commentary, vast multimedia universes and timelines. But the thing that I will always most admire, most distinctly and profoundly feel, is the basic, crucial trick that Rowling pulls off at the very beginning: Wish fulfillment. The sense of escape, of experiencing a dreamy version of our own life, is remarkable. I still sometimes see jokes like “I’m almost thirty and am still waiting for my Hogwarts letter,” and I empathize every time.

⚡⚡⚡

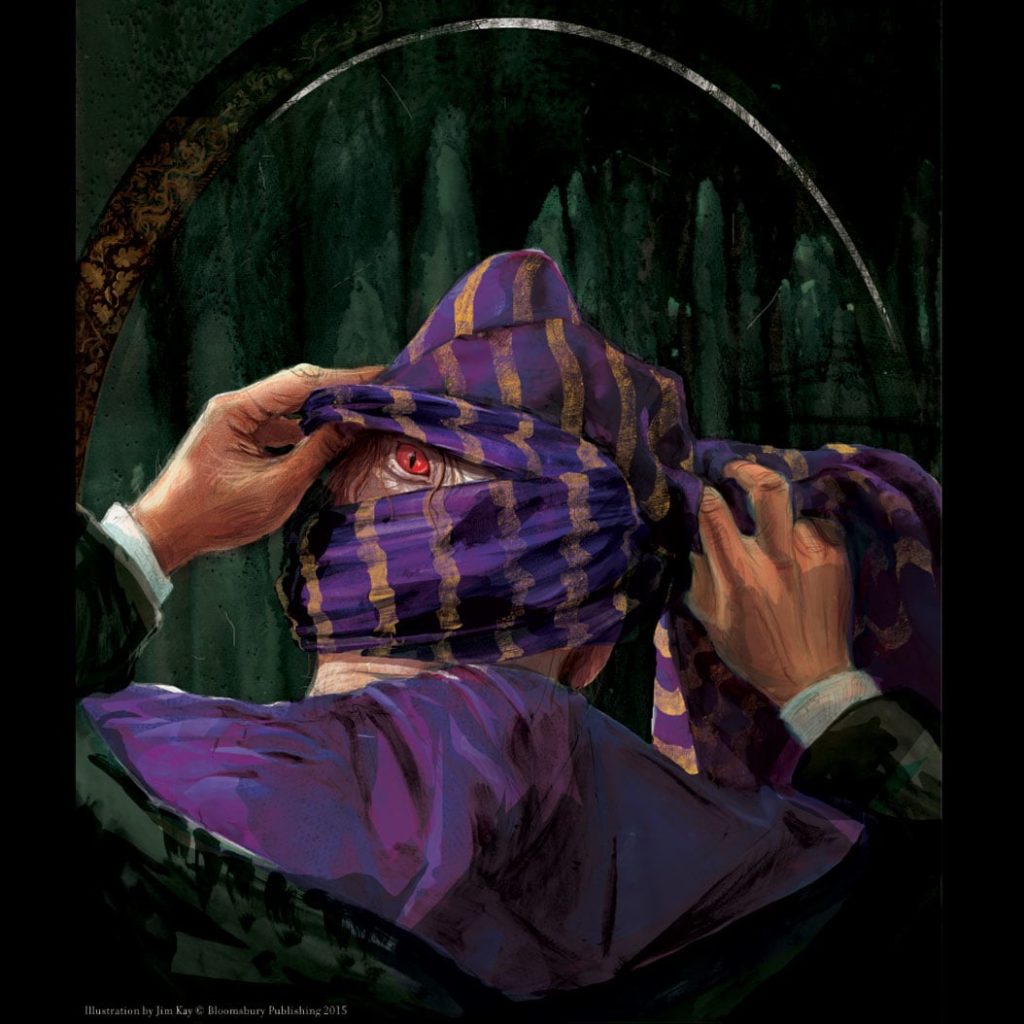

It took me no more than a few days to get through that first book. I was already in, hook, line, and sinker — and then Rowling pulled out one of the great endings in the history of children’s literature. After a riveting and tense climax, we learn that the mastermind villain is not the curmudgeonly Professor Snape, but the cowardly Professor Quirrell, who had lingered on the edges of every pivotal scene without notice.

It’s difficult to overstate how influential this one storytelling moment was to me. Since then, I’ve been forever searching out the perfect plot twist like a junkie craving his high. A good twist needs to be unexpected but plausible, needs to reframe everything that happened without rendering it meaningless. Few writers manage to nail it once; Rowling went 7 for 7. (Though I still think “Moody drinking Polyjuice Potion” is the weak link.)

It’s more than the “egads!” moment, though. Snape emerging as a reluctant ally, not a villain, during the ending of Sorcerer’s Stone, is an important hint of what was to come in the series: The line between good and evil would blur, and we couldn’t always trust our first impressions. (Though, sure enough, Draco was always a toolbag.)

I think this is what makes Harry Potter books so addictive: the gradual trickles of information and reversals of expectations before a jaw dropping ending.

It might be Rowling’s greatest writing skill: Narrative misdirection. We think the story is headed one way due to careful framing and perspective control, then we learn just how wrong Harry’s hunches were.

(The sixth book provided the most interesting meta-twist on this element of the series. By then, readers were used to learning that Harry’s first guesses were wrong, but Half-Blood Prince flipped the script by making Harry’s first guesses — that Draco was in deep with Voldemort and going to cause serious trouble, that Snape was hiding dark secrets and plans — right all along.)

⚡⚡⚡

Within a few weeks, I got my hands on books 2 and 3. I devoured them.

And each time I got to the end, I had the same thought: “That was easily the best book yet. There’s no way the next one can top it.”

One thing Rowling did is gradually ramp up the complexity of the plots, premises, conflicts, and character development. In short she made sure the books weren’t just fun, but offered depth — which emerged gradually and consistently.

The series is a perfect blend of episodic adventure and continuous epic: each book is a self-contained story with a familiar structure (a school year mystery) that also develops the characters, expands the world and lore, deepens the complex moral commentary, and raises the stakes of an epic final showdown.

Much of the series’ depth comes from new shades and dimensions given to nearly every member of the series’ huge cast of characters.

The character who most famously benefited from this type of depth was potions master Severus Snape: He’s written as the villain in the first book, before the surprise that he was actually protecting Harry. We learn he has a complex relationship not only with Harry’s late parents (resents Dad, friendzoned by Mom), but with Harry’s saga itself (he shared the Prophecy with Voldemort, leading to Voldemort attacking Harry, James, and Lily).

By the end of the series, Snape ends up at the center of Harry’s saga nearly as much as Harry himself. His flashback chapter near the saga’s conclusion, “The Prince’s Tale,” is one of the most revered moments of the series.

Snape is plenty fascinating, but my personal take is that the character who most emerged over the course of the series — my favorite Harry Potter character — is Neville Longbottom. In Sorcerer’s Stone, he’s bumbling comic relief struggling to preserve his dignity (before a final brave turn to give Gryffindor the House Cup). But as we learn about his history and his odd parallels to Harry, he becomes a tragic, resilient hero — determined to make sure Voldemort and his cronies receive justice, and to prevent anyone else from suffering the way he and his parents have. He’s not a great wizard, but that just makes him more heroic.

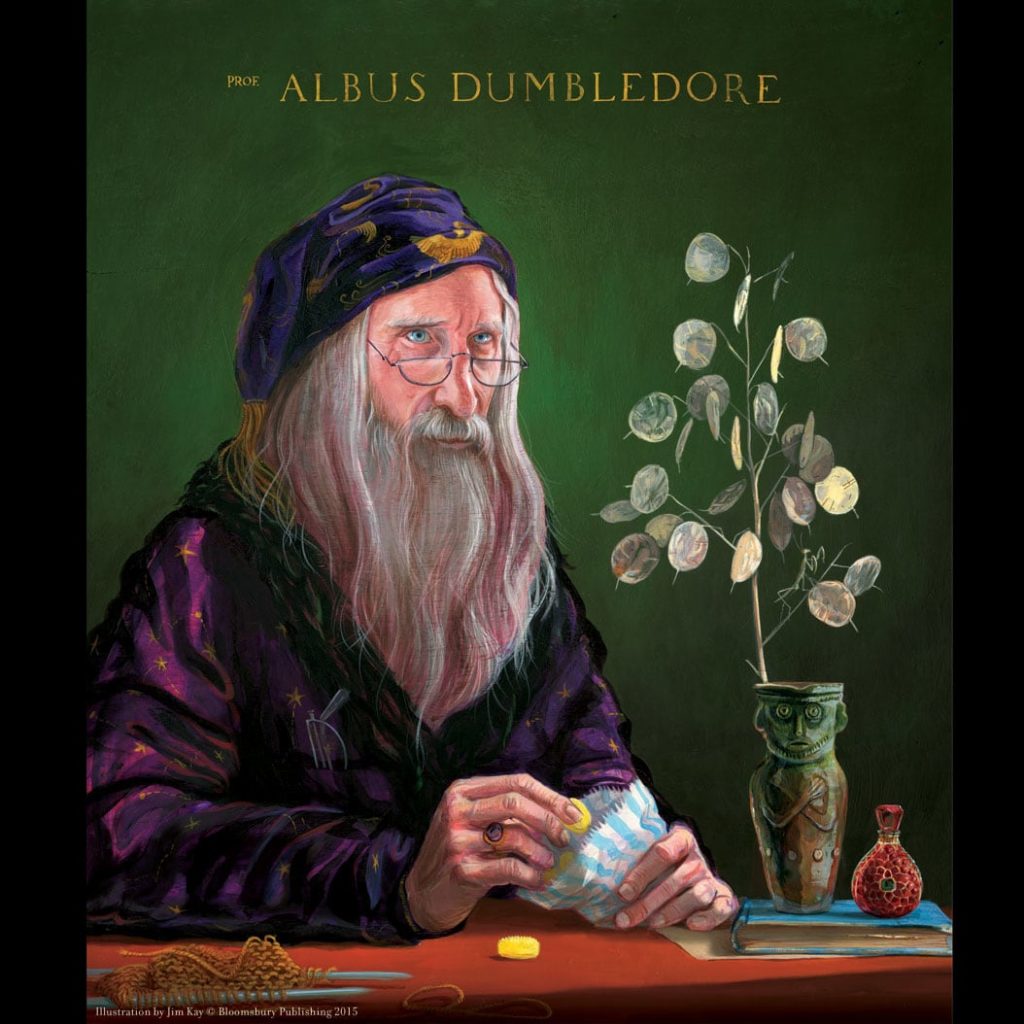

This depth goes for nearly everyone: the principled but Machiavellian Dumbledore, the heart-of-gold half-breed Hagrid, the stand-in parent Sirius Black, etc. etc. etc. It’s the characters that drive the series’ cavernous depth, and everyone gets moments to shine and grow.

⚡⚡⚡

By the time I finished Book 3 in 1999 or 2000, I was caught up on the series, and of course hungry for more. I learned from the newspaper the release date of the next book, The Goblet of Fire, and saw it was the upcoming summer.

Thus began the first time of many that I’d experience a special piece of growing up with Harry Potter: anticipation and ritual.

My mom ordered the book for me (or reserved it at the library; I can’t remember which), and I counted down the days. I reread the whole series up to that point, something I would do with every subsequent release.

The newspaper and/or internet would include a description of the book, and my friends and family and I would speculate on what might happen. For the later books in the series, I even scoured forums for fan-written theories.

Then the book would finally arrive and take over my world for a few days. Every waking moment was reading that book until the final page was turned.

There was a rhythm to the process, and the long wait between each book (though rookie length by ASOIAF standards) always refueled my anticipation to do it all over.

Just as I had my own reading routine, so each book had a consistent framework, with only slight variations each time (excluding Book 7): Mistreatment at the hands of the Dursleys, inciting magical moment on Privet Drive, trip on the Hogwarts Express, rivalry with Malfoy, familiar adolescent rituals with a magical spin, pesky new Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher, murmurs and revelations about Voldemort, troubles in class, hints of rising danger, a final descent to the climax at a gate of Hades of some sort, a faceoff with Voldemort and his yearly sidekick, unlikely victory achieved through inner strength and a divine blessing, a recap with Dumbledore, and a farewell to the hallowed school grounds. Rinse and repeat next school year.

Mistreatment at the hands of the Dursleys, inciting magical moment on Privet Drive, trip on the Hogwarts Express, rivalry with Malfoy, familiar adolescent rituals with a magical spin, pesky new Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher, murmurs and revelations about Voldemort, troubles in class, hints of rising danger, a final descent to the climax at a gate of Hades of some sort, a faceoff with Voldemort and his yearly sidekick, unlikely victory achieved through inner strength and a divine blessing, a recap with Dumbledore, and a farewell to the hallowed school grounds. Rinse and repeat next school year.

The cadence of it all, of Harry finding everything mostly the same but also different, resonated with me as a kid: It echoed not only how I experienced the books, but how I experienced my own life, year after year.

⚡⚡⚡

A reader’s first trip through any Harry Potter book is focused on the tension and mystery. How is Voldemort involved this time? Who is his agent of evil? What mysterious power or secret will Harry unlock? Who’s going to win the next Quidditch match? (Just kidding, nobody cares about Quidditch.)

It’s on rereads that Rowling’s worldbuilding shines. She’s crafted an evocative, postmodern world filled with biting commentary and clever juxtapositions.

I call it a “postmodern” world because of how much the setting and details react to, and reject, the Tolkien-driven “modernist” perspective that magic is rare and sacred and affirming. So much of Harry Potter’s worldbuilding is in minutiae that reminds us that people who use magic are ordinary people, too: They have to do laundry and work in a dingy office. They cheer for sports teams and bicker with siblings. Rowling asks what rustic England would like if everyone had magic, and answers clearly: The extraordinary becomes ordinary.

Among the series’ greatest triumphs is its depiction of institutions. As Harry’s educational career progresses, and Voldemort’s return escalates, the “powers that be” in the Ministry of Magic become more incompetent and intrusive.

In the first book, there’s little more than a few asides about the government’s incompetence. In Chamber of Secrets, Hagrid is wrongly, though understandably, imprisoned, and the Ministry threatens to shut down Hogwarts. In Prisoner of Azkaban, the government bumbles through an attempt to capture an escaped convict; they also, quite literally, use soul-sucking fear to impose their will. (It’s no stretch to say the Dementors are one of the great fantasy creature creations of the past century.)

By the series mid-point, Rowling had made clear that the Ministry’s malignant incompetence is as much the saga’s villain as is the cackling big baddie. From the fourth book on, she’d only escalate this theme: In Goblet, we get vivid governmental conspiracies and misdeeds as Ministry workers botch the world cup and Triwizard Tournament amid rising darkness: It’s Crouch’s hypocrisy in freeing his son and lying about it that allows Voldemort to rise again.

Of course, Order of the Phoenix gives us the most memorable instance of the Ministry putting fear and stasis ahead of progress: Dolores Umbridge as the cruel DADA teacher, who is perhaps Rowling’s greatest villain. By Half-Blood Prince, the Ministry is actively working against Harry’s attempts to thwart evil, and in Deathly Hallows, there’s literally no line between evil and bureaucracy.

While Rowling’s cynicism towards politics felt a little harsh during the “Yes We Can” Obama years, let’s just say that particular facet of her world has rung pretty true since since November 2016.

⚡⚡⚡

In the summer of 2007, I had just suffered through a dispiriting freshman year of college. I’d broken up with my first girlfriend, struggled through poor grades and a lonely social life, and battled a minor bout of depression. Worst of all: Harry Potter, my favorite book series, was coming to an end. Dark times, indeed.

It didn’t take long for hope to return. I got back together with my girlfriend the following spring (we married a few years later). I transferred to a new school where I made more friends and had more fun. Lastly, I recovered from the end of the Harry Potter by dipping my toe in its warm, vibrant community of fans and creators and extended universe content. From official movies to goofy parodies to spinoff epics, there’s never been a lack of content to scratch my Hogwarts itch.

It goes deeper than that, though. There’s a podcast called “Harry Potter and the Sacred Text” which posits an idea I find compelling: My generation’s world outlook is steeped in the stories and morals of Harry Potter. JK Rowling’s work literally shaped millennials’ souls, and hundreds of thousands of us continue to commune in its honor at festivals and theme parks and stage shows and parties.

Harry Potter completely reshaped the way we talked about kids’ literature, allowing it to be longer and deeper and more challenging. It changed the way fans engage with culture — especially with the internet. It supercharged the careers of dozens of online creators.

(In fact, you can draw a line between Harry Potter and my favorite author, John Green. His brother was connected to Harry Potter fandom, which expanded the popularity of their YouTube channel, which jumpstarted Green’s authorial career. Without Harry Potter, we might have no “I was a drizzle and she was a hurricane” and no Hazel Grace and no Anthropocene Reviewed. Green raised the literary quality and prestige of YA lit — another Harry Potter ripple.)

If you want content and a community, then Harry Potter and its world will have more than you can ever hope for — then, now, and for the indefinite future. There aren’t many pieces of fiction you can say that about.

⚡⚡⚡

I’m a dad in my thirties now. The first Harry Potter book came out more than two decades ago. The last, thirteen years ago.

It’s undeniable: I’m old, and so is this series. I watch the Harry Potter entry of the legendary Parking Lot series and it breaks my brain. It’s a vision of how I see the world, but also incomprehensibly dated. My fractured consciousness, split between the present and the distant past, can feel its impending obsolescence in that grainy footage.

And Harry Potter, too, is undoubtedly aging. No thanks to a middling spinoff movie series, a critically panned follow-up book/play, and Rowling’s diminishing reputation (especially due to constant transphobic comments), the series is becoming a relic.

And yet… I believe there is a timelessness to Harry Potter. There will always be bullies. There will always be the need for courage in the face of adversity. There will always need to be kindness to oppose bigotry and fear. There will always be that one smart kid who gets all the shit done herself.

I have two daughters, a three-year-old and an eight-month-old. I started reading Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone to my older daughter the day she was born, and we finished Deathly Hallows nine months later. Of course she didn’t understand a word of it, but it was still great family bonding. (It also inspired me to finally publish my own ranking of the books.)

We are now part way through our second read-through, daughter number two included this time. We’re using Jim Kay’s phenomenal illustrated editions (all the pictures in this post are by Kay). The older daughter is really into it. She says her favorite character is Hermione, and she finds Dobby very creepy. The younger daughter gave a glowing review of “bah bah bah.”

It’s truly a delight to pass this series on to the next generation, to relive Rowling’s great adventure through the eyes of children.

I hope they continue to love the series as they grow, even as I know they will never love it as much as I do, or in the way I do. That’s okay; it’s good, even. I want them to have their own stories to cherish and worlds to discover. I want them to find their own art to pass on to their own kids some day. They need not be beholden to my taste alone.

Though I can’t give them the same formative literary experience I had, I hope the Harry Potter series is something special for them in a different way: A reminder that their daddy loves them more than Ron loves Chocolate Frogs and wants them to have their own great journey. Thankfully, their saga doesn’t begin at Privet Drive.

Culture is more than ink on a paper, more than grooves on a vinyl, more than frames on a film reel. It’s the fundamental human experience of shared stories and collective memory. It’s the lens through which we view the world, and passage of time, and all basic truths of human nature. And that has never been more clear to me than when I’m reading Harry Potter.