100 Film Favorites – #56: Charlotte’s Web

(Charles A. Nichols & Iwao Takamoto, 1973)

Note: When I first wrote this entry, the previous post about Titanic had just become the most-viewed post to date on my Brian Terrill Movie Night page, topping 300 views. I was coming down off a powerful view-high, so if the tone is noticeably different, that’s why.

Note: When I first wrote this entry, the previous post about Titanic had just become the most-viewed post to date on my Brian Terrill Movie Night page, topping 300 views. I was coming down off a powerful view-high, so if the tone is noticeably different, that’s why.

Charlotte’s Web was the first theatrically-released feature film by Hanna-Barbera productions not based on their own established characters (after 1964’s Hey There, It’s Yogi Bear! and 1966’s The Man Called Flintstone). An animated adaptation of E.B. White’s novel of the same name, the movie tells the story of Wilbur, a pig who is saved from slaughter through the ministrations of a spider.

One spring morning, a litter of piglets is born on the Arable farm. When one small piglet becomes obvious as the runt of the litter, farmer Arable heads into the barnyard with an axe to “do away with it.” This greatly distresses the farmer’s daughter Fern, who makes an impassioned plea for the young pig’s life. Mr. Arable acquiesces, and Fern begins raising the tiny pig, whom she names Wilbur.

Over the following weeks, Wilbur grows considerably, and soon farmer Arable decides the pig must move to the larger farm of Fern’s uncle, Homer Zuckerman. Though Fern is sad to see him go, she travels to the Zuckerman farm frequently to visit him. Despite these visits, Wilbur is still lonely and sad, particularly when he learns that a pig’s “purpose” in life is to be fattened and slaughtered.

The first animal to befriend Wilbur is Charlotte, an orb-weaver spider living in the rafters of the Zuckermans’ barn. Seeing how distraught Wilbur is at the prospect of being turned into “crunchy bacon,” Charlotte resolves to do what she can to save him from this plight. That night, while the other animals sleep, she spins a web with the words “SOME PIG” wrought in the middle over Wilbur’s pen. In short order, news media are flocking to the Zuckerman place, eager to report on the “miracle” at hand, and the remarkable pig who inspired it.

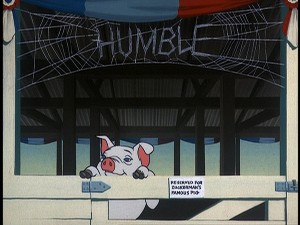

Soon the original message fades, and Charlotte endeavors to expand her vocabulary. In the coming weeks, the web above Wilbur’s pen variously reads “TERRIFIC,” “RADIANT,” and “HUMBLE.” The fervor inspired by this phenomenon leads Zuckerman to exhibit Wilbur at the state fair, where “Zuckerman’s Famous Pig” becomes the guest of honor in a parade. During the resultant celebration, Homer Zuckerman officially declares that he will never slaughter Wilbur.

Wilbur returns to the barn to tell Charlotte the good news. There, he finds her putting the last touches on her “magnum opus,” an egg sac. Charlotte implores Wilbur to defend the sac, as she herself will soon die. Wilbur is distraught, but promises to comply with her wishes. Charlotte retreats into the rafters and dies.

Eventually the egg sac hatches, and Wilbur is excited to make friends with all of Charlotte’s more than 500 progeny. However, nearly all of the spiderlings depart immediately via “parachute,” casting a string of web into the wind and sailing far away from the Zuckerman farm. Wilbur is lonely once again, until he finds three of Charlotte’s children who opted to stay. Wilbur names the spiderlings, and promises to tell them all the story of their mother and her sacrifice.

Charlotte’s Web is a musical in the Disney tradition. The film even features songs by the Sherman Brothers, the music-and-lyrics team who had been Disney’s go-to composers throughout the 60s and into the 70s. The Shermans crafted the songs for The Sword in the Stone, The Jungle Book, The Aristocats, assorted live-action films including the wildly successful Mary Poppins, and two 1964 World’s Fair attractions which would later move to Disney theme parks: General Electric’s Carousel of Progress, and, perhaps their most notorious contribution to the 20th century soundscape, Pepsi/UNICEF’s It’s a Small World (After All).

The songs throughout Charlotte’s Web are a strong and memorable aspect of the film. They run the gamut from bouncy, upbeat numbers (“I Can Talk,” “Chin Up,” “We’ve Got Lots in Common”) to ones which are touching, dark, and sad. Every song is unique and captures its respective emotion well: The titular song is a mysterious, minor-key lullabye on harpsichord which plays when Charlotte spins her messages at night. “Smorgasbord” depicts the nocturnal journey of Templeton the rat, who, tasked by Charlotte with seeking out advertising copy to help her “advertise” Wilbur, travels to the fair and gorges himself on various discarded food items. “Mother Earth and Father Time,” a song played as Charlotte dies, is a slow, tender song about the fleeting nature of time, and “how very lucky are we, for just a moment to be, part of life’s eternal rhyme.”

It’s the film’s ability to capture this passage of time that really makes it stand out. Like Bambi or Milo and Otis, Charlotte’s Web depicts a short period of time (a year or so), but since the protagonists are animals, we see much of their lives unfold in that time, with a new cycle ready to begin as the next year rolls around. Tying the “circle of life” to the cyclical nature of the seasons is powerful symbolism, but Charlotte’s Web improves on this formula by throwing human characters into the mix as well. Over the course of the year, while Charlotte’s entire life, and much of Wilbur’s, play out, Fern and the other human characters are growing too, if more slowly. Henry Fussy, a minor character who begins the story a nerdy, repressed boy, takes a formative trip, where he smashes his violin and spends the summer hunting and fishing. Henry returns comparatively hunky, and Fern is soon more interested in him than her pet pig.

E.B. White was largely displeased with the adaptation of his novel, complaining that the action is interrupted every few minutes for the characters to break into “a jolly song,” and that he would have preferred a score of Mozart rather than Broadway/Tin Pan Alley-style songs. But all in all, as I’ve said, the songs contribute to the emotional impact of the film, and comprise a noteworthy corner of the Sherman Brothers’ impressive library. Charlotte’s Web is a memorable musical which doesn’t hold back on the heavier, darker elements of the book’s plot and themes.

Tidbits:

In recent years, I’ve wondered the following, and why more people aren’t talking about it – Why does Charlotte’s web reading “Some Pig” cause people to marvel at Wilbur…when he doesn’t actually DO anything? Shouldn’t the visiting media be marveling at the spider’s ability to spell? Is Charlotte’s Web actually a satire on people taking advertising at face value, and absent-mindedly doing and thinking what it tells us to?

—

Brian Terrill is the host of television show Count Gauntly’s Horrors from the Public Domain. You can keep up with Brian’s 100 Film Favorites countdown here.

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you writing

this article and also the rest of the website is very good.