Album rating: 4.5 stars (out of 5)

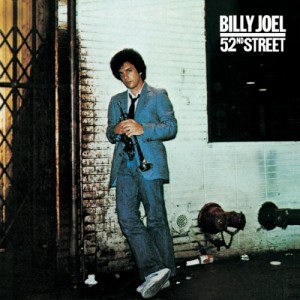

52nd Street is The Stranger‘s jazzy little cousin, not quite so sophisticated or psychologically complex but a gem in its own right.

Instead of basking in his new superstardom, Billy Joel hurried back into the recording studio after The Stranger elevated him to top of the charts and to magazine covers.

The result is that 52nd Street is not quite so deeply felt and personal as The Stranger, but equally inspired musically. Phil Ramone returns as producer and, on the whole, does even better than he did on The Stranger. Every track here sounds just right and avoids feeling dated 35 years later, which can’t be said for Just the Way You Are.

There’s a certain argument to be made that 52nd Street is a “re-write” of The Stranger. You can definitely find some thematic similarities — Zanzibar, Stiletto, and Rosalinda’s Eyes are just as horny, slyly derogatory, and swooning (respectively) as Only the Good Die Young, She’s Always a Woman, and Just the Way You Are.

But 52nd Street is inventive enough enough musically and strong enough in its compositions to never feel like a re-tread. Joel’s words are shallower and less compelling than The Stranger or Turnstiles, but it’s every bit the equal to those peaks in its performances and tunes.

There’s a disjointed feeling to 52nd Street: the opening three tracks sound like a direct sequel to single machine The Stranger, while the rest of the album is a mini-concept album of Joel integrating disparate jazz styles into pop compositions.

Fortunately, virtually every component of 52nd Street works, and the package as a whole is satisfying, fun, and dense with classics.

Joel opens the album with three reactions to his new superstar fame: none of them positive looks, but all of them great singles.

Before he broke big, it always seemed like Joel careened towards stardom reluctantly. From his opening album onward, he has struggled with the cognitive dissonance between his appealing sound and a resentment for the growing fame his music brought him.

Thus, it’s no surprise that Joel has his apprehensions with his new attention. From his regrets at his substance-fueled bad behavior and abrasiveness (Big Shot) to his lack of privacy (My Life) to the brown-nosers (Honesty), Joel seems focused on the downsides of huge success.

The cream of this crop is My Life, one of the best singles Joel ever released. It’s a fine bit of pop alchemy. Joel and Ramone transmute various sounds into a radio-ready gem. The background gospel choir mesh brilliantly with the keyboard part, the piano, and the guitar strums to delectable effect.

My Life has had a fantastic durability, and it remains a staple of oldies and mix radio stations. In fact, the radio cut may be the best version of the song: the piano verse (present on the album track, cut on the radio version) is nice, but redundant and drags the track out to almost five minutes.

Big Shot, meanwhile, boasts a stylized and perfectly executed vocal performance from Billy Joel. I’ve heard live versions and covers, and they’re not pretty: Joel’s always underrated vocal versatility elevates the song to greatness.

The lyrics of Big Shot seem more ominous knowing the substance abuse that Joel has struggled with in recent years. Though Joel seems to be addressing someone else in the lyrics who parties a little bit too hard and loses control, it’s hard not to think that he was writing this song to himself.

I’m of two minds regarding Honesty. The song’s blunt lyrics, begging for some impossible honesty, struck a chord with a large audience. But I find them off-putting and whiny rather than earnest. This is an instance where Joel’s self-pity crosses over into unpleasant.

Fortunately, the lamenting ballad that backs up Honesty connects far more than the lyrics. Joel again gives a splendid vocal performance and prevents the song from breaking under its own weight.

Tracks four through nine present a different twist on Joel’s refined sound. Each has a structural or sonic twist inspired by some flavor of jazz. From the instrumentation, to the intros and riffs between verses, to syncopated background beats, each track appropriates something unconventional to make this a particularly memorable stretch of non-singles.

The two most striking songs here are Zanzibar and Stiletto. The former is stylized with some unusual chords, long boppy trumpet solos, and references to a jazz bar. Though it’s adventurous and memorable, it’s one of the least successful tracks on the album. The trumpet solos — impressively performed by the late Freddie Hubbard — break up the momentum of the track and feel out of place.

The lyrics of Zanzibar, too, weigh the track down. Joel’s lusting for a waitress is infinitely less charming (and less perversely funny) than his ode to Catholic school girls, Only the Good Die Young. His “I’m a big boy now” frat refrain mixed with some fairly obtuse sports metaphors do little to help.

Stiletto, on the other hand, works brilliantly. Its syncopated, boogie-woogie piano in the background is the most memorable feature of the song, but the energetic melody and jaded lyrics are also strong points.

Equally strong is ballad Rosalinda’s Eyes, a ballad written from the perspective of his dad about his mom. The Latin jazz keyboard intro is a bit soggy, but Joel’s heartfelt vocal performance, and, moreso, his impassioned lyrics steal the show. This may be the most under-appreciated ballad in Joel’s discography. The line “I can always find my Cuban skies in Rosalinda’s eyes” is probably my favorite lyric about pretty eyes (with apologies to the Old 97’s Big Brown Eyes).

The high mark of the album continues with the uptempo Half a Mile Away. The brass instrumentation suggests an unorthodox, jazzy composition, but this is pure pop bliss. Joel and his band wouldn’t sound more like Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons until Uptown Girl. I still think of Half a Mile Away as one of Joel’s most surprising non-singles.

Half a Mile Away explores Joel’s lingering blue collar streak and his attempt to reconcile his celebrity with his laid back, everyman roots. From a thematic perspective, it’s one of the most interesting tracks on the album.

But the most fascinating track on the album is the show-stopping, Broadway ballad Until the Night. A repeating bass chord gives the song an emotional heartbeat, and the string orchestra ramps up the theatrical intensity.

The music matches the beautiful lyrics Joel penned to accompany it. Joel sings about postponed love and rekindled passion with such intensity that it’s hard to believe it wasn’t written for someone special.

Until the Night would have served as a memorable conclusion to 52nd Street, but Joel opted to go out an throwaway grace note. It’s a shame. 52nd Street, the name of the closing track, has little more than a nice piano riff to distinguish itself.

The closing track ends a streak dating back to the first track of Turnstiles of every one of Joel’s tracks being good or great or, at a minimum, daring. He always finds opening tracks that capture the spirit of his albums, but rarely does Joel end albums on a high point.

The minor missteps of the album do little to tarnish 52nd Street‘s luster. Hits like My Life and Big Shot shine, but it’s the back end of album tracks that really give 52nd Street its jazzy soul. Rosalinda’s Eyes, Stiletto, Until the Night, and Half a Mile Away should be on the short list of any Joel fan looking to explore tracks beyond Greatest Hits albums.

It’s not as intensely personal or revealing as The Stranger, but 52nd Street is nearly as convincing and spectacular. It’s one of Joel’s best albums.